‘There was a wave of Russian films which made their way to London during the eighties/nineties which I adored. None more so than Tarkovsky…I believe Tarkovsky’s work has had an influence on my life and work in much the same way that certain key experiences stay with and enrich our lives, become points of reference and renewal. Seeing my first Tarkovsky film was to experience an epiphany of sorts. It registered deeply and profoundly.’ (DS, 1999)

In 1986, as Sylvian released Gone to Earth and found the material for the next solo album coming to him unexpectedly and freely, Russian film director Andrei Tarkovsky unveiled what was to be his final movie – The Sacrifice. Illness had dogged the director during filming the previous the year, and he supervised the dubbing and editing of the film largely from hospital where he was being treated for lung cancer. He died on 29 December 1986.

Sylvian’s revelatory experience of Tarkovsky was likely to have been earlier. The film-maker’s penultimate picture, released in 1983, was named Nostalghia. It’s probably not a coincidence that a song of the same name appeared on Sylvian’s Brilliant Trees which was being recorded that same year – an album where literary and artistic references are scattered amongst the lyrics with scant disguise. There can be no doubt about the influence of The Sacrifice on 1987’s Secrets of the Beehive, Sylvian telling radio presenter Alan Bangs in an interview to support the release, ‘there was a track on the album which related to one of Tarkovsky’s films, the last one he made – The Sacrifice. ‘Maria’ is a kind of… it relates to that film in some way. It’s a kind of personal tribute to Tarkovsky.’

The Sacrifice is a long watch at two hours and twenty minutes. We are so used to movies being served to us as fast-moving entertainment in twenty-first century culture; Tarkovsky’s work might as well be in a different medium altogether. His is cinema as art. He saw a parallel between the cinematographer and the poet, crafting many layers of significance for us to experience, appreciate and reflect upon. Events develop slowly, observed through long and subtly moving single camera shots. It’s not an easy film to view, and yet at the same time it’s captivating.

Sylvian’s song is named after one of the characters in the The Sacrifice. To catch a glimpse of the significance of the reference it’s worth recounting something of the plot and its presentation. The film opens with credits sound-tracked with sacred choral music by J.S. Bach, and a long static shot of a detail from Leonardo Da Vinci’s painting The Adoration of the Magi. Our attention is focused towards one of the visiting wise men kneeling before the Christ-child and proffering his gift. The painting is a recurring motif, maintaining the presence of Mary, the Holy Mother, throughout the movie. There follows a scene in which the film’s protagonist, Alexander, is planting what appear to be barren branches by the seaside, recounting to his mute son ‘Little Man’ the story of a monk who faithfully watered a dead tree for years and was finally rewarded when it burst into life.

It’s Alexander’s birthday, but the gathering of his family, doctor Victor and postman/friend Otto is interrupted by the rumbling of jets overhead and the radio news which communicates the onset of war, triggering the desperate fear of nuclear holocaust. Distraught, Alexander makes a pledge to God to sacrifice all that he loves, even his son, if mankind can be spared the suffering. Otto is an avid collector of stories of strange occurrences, and amidst the trauma he tells Alexander that if he sleeps with the servant Maria, whom he describes as a witch, disaster can be averted. Alexander visits Maria and the pair levitate above her bed as Otto’s bidding is carried out.

The next day, everything seems back to normal. In line with his vow, Alexander sets about giving up all that is dear to him, setting fire to his house in a spectacularly-filmed single sequence, and – now mute like his son – submitting himself to medics who take him away from his family. In a final scene, as Alexander is driven past, ‘Little Man’ is watering the tree they planted together. Freed to speak, the boy utters the biblical words, ‘In the beginning was the Word,’ ending the film with the question, ‘Why is that Papa?’

The Sacrifice feels as bleak as its cold war setting, but there is hope. Nuclear catastrophe is indeed averted, perhaps miraculously – albeit the spiritual link is ambiguous: was it Alexander’s entreaty to God that made the difference, or was it his encounter with Maria? Are these two occurrences connected, or perhaps neither brought salvation?

Of course a summary here can only be a gross simplification of over 140 minutes of cinema, but there are themes that resonate with Sylvian’s work. By his own admission he had been letting go of the tenets of the Christian faith since Brilliant Trees, perhaps before, yet he can’t seem to shift from the imagery. Secrets of the Beehive includes references to ‘the crosses of old grey churches’, the devil, and ‘Mother and Child’ conjures up a nativity scene, especially with its reference to ‘Jesus’ name’. The ambivalent spirituality of The Sacrifice and conscious wordplay of Mary/Maria resonates somehow with that uncertainty. Is Maria really a witch, or is she somehow providing a route to the divine? All this questioning is summed up in the film’s final spoken line.

Even the samples employed in the track play to this theme of how individuals find a connection with the spiritual realm. First there is a delightfully mysterious laugh. ‘It came from a recording I made from the radio. It was of some strange man that had been living with some Indian shamans. He was just telling these strange stories and I just thought that laugh was wonderful, and so I thought I would use that one day.’ (DS, 1987)

Then there follows the spoken word:

‘One hand lifted up to God,

The other pointing to the earth’

This could be a picture of a mediator connecting heaven and earth, but might equally imply that the hand stretches skyward in vain, echoing the ‘reaching up like a flower, leading my life back to the soil’ of ‘Brilliant Trees‘.

The images employed in Sylvian’s lyric create scenes that could be straight out of a Tarkovsky film:

‘“Climb the stairs

And step into my dream house”

These words are yours, Maria

The water’s warm (Hold me)

The table bare (’til the worst is past)

Until the summer nights return

Until we close our eyes’

The vocals are multi-tracked so that Sylvian provides backing to his own lead, the supporting part sung in his little-used higher register – later heard on Rain Tree Crow’s ‘Pocket Full of Change’ – with the two phrases following on from one another: ‘Hold me/’til the worst is past’. Sylvian seems to find in Maria the embodiment of a desire to connect with the spiritual side of life. Her attention and embrace sustain the song’s protagonist in the hope of brighter times to come.

‘Maria, your every thought’s my heartbeat

Maria, save a thought for me’

I love the care and precision in the diction as those lines are delivered.

In the final year of his life Tarkovsky published a book in which he discusses his own art, titled Sculpting in Time. He offers there a description of the maid Maria and her impact on the lead character in The Sacrifice. ‘Maria is the antithesis of [Alexander’s wife] Adelaide; modest, timid, perpetually uncertain of herself. At the beginning of the film anything like friendship between her and the master of the house would be unthinkable; the differences that separate them are too great. But one night they come together, and that night is the turning point in Alexander’s life. In the face of imminent catastrophe he perceives the love of this simple woman as a gift from God, as a justification of his entire life. The miracle that overtakes Alexander transfigures him.’

For Tarkovsky, it’s the audience who should determine the significance of the film’s events in the context of their own experience and understanding. Again from Sculpting in Time: ‘The metaphor of the film is consistent with the action and needs no elucidation. I knew that the film would be open to a number of interpretations, but I deliberately avoided pointing to specific conclusions because I considered that those were for the audience to reach independently. Indeed, it was my intention to invite different responses. I naturally have my own views on the film, and I think that the person who sees it will be able to interpret the events it portrays and make up his own mind about the various threads that run through it and about its contradictions.’

Sylvian expressed a similar sensibility relating to his music in the radio interview with Alan Bangs, when challenged as to whether his work could go beyond providing enjoyment into provoking people in some way. ‘I think my music causes the listener to look within themselves in some way, causes introspection…I think that’s why some people feel uncomfortable with my work. But I see it as a positive element…I’d like to think that it would force them to look within themselves and ask themselves questions – and come up with answers for themselves, because for me that’s the most useful aspect I think my work could possibly have, is to help people find their real selves.’ (1987)

Sylvian also admitted that the sleeve artwork for Secrets of the Beehive could be a reference to Tarkovsky: ‘I’m a great admirer of Tarkovsky’s work and so, I think, is Nigel Grierson the photographer who took the photograph on the front of the cover. So yes, possibly. I mean there weren’t many words spoken about what he should be doing for the cover. I left it really up to him what he wanted to do’ (1987). One image in particular from the cover appears to directly reference the core metaphor from The Sacrifice:

Tarkovsky: ‘Has man any hope of survival in the face of all the patent signs of impending apocalyptic silence? Perhaps an answer to that question is to be found in the legend of the parched tree, deprived of the water of life, on which I based this film which has such a crucial place in my artistic biography: the Monk, step by step and bucket by bucket, carried water up the hill to the dry tree, believing implicitly that his act was necessary and never for an instant wavering in his belief in the miraculous power of his own faith in God. He lived to see the Miracle: one morning the tree burst into life, its branches covered with young leaves. And that “miracle” is surely no more than the truth.’

It’s an image that stuck in Sylvian’s mind. Speaking later about R.S. Thomas, the inspiration for ‘Manafon’, he said, ‘For all its apparent bitterness and tragicomic contradictions there’s something beautiful about the man’s dogged devotion to writing, to poetry. Like the character in Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice who everyday waters the dead tree in the belief that one day it’ll return to life. This is the work of faith, isn’t it?’ (2009)

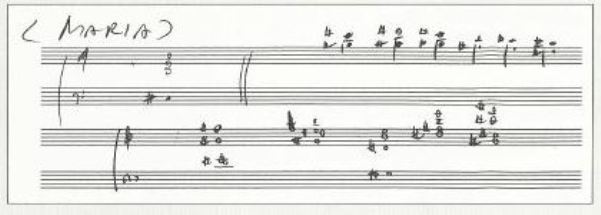

Musically, ‘Maria’ comes from a trio of Ryuichi Sakamoto, David Torn and Sylvian himself. There are layers of keyboard sound including a warbling synthesiser line which moves around in the stereo mix, surrounding the main parts. Sylvian admitted that this was the only track where he didn’t stay true to his concept of acoustic instrumentation on Secrets…, lending it a distinctive feel amongst the album’s songs. Torn’s atmospheric guitar loop – which he later explained was played on koto guitar – combines indecipherably with the synth sounds and the sustained notes of Sakamoto’s string arrangement, accompanied by the chimes of a faraway bell. Everything contributes to the perfect sound environment for Sylvian’s vocal. ‘There’s a quality in the low range of his voice that’s incredible, it’s unbelievably powerful and resonant.’ (David Torn, 1988)

Ryuichi Sakamoto also cites Andrei Tarkovsky as a major influence on his life and work. ‘I am a long-time fan of his films. He only left seven masterpieces, and I have watched them again and again throughout my life, but recently I like his films more than before, maybe because of age, maybe the disease. Maybe my experience with cancer is more related to the concepts of his films – life and death and memories. His films are full of poetry.’ (RS, 2017)

Sakamoto describes his 2017 album async as, ‘a soundtrack for an imaginary Tarkovsky film, a film that only exists in my brain.’ Stephen Nomura Schible’s insightful film-documentary about Sakamoto, Coda (2018), shows Sakamoto recording the album, capturing the natural sound environment around him to use as raw material. Tarkovsky said, ‘Above all, I feel that the sounds of this world are so beautiful in themselves that if only we could learn to listen to them properly, cinema would have no need of music at all.’ It’s a principle that Ryuichi adopts for his soundtrack to a film never made. ‘I think the steps – the sound of steps is always a very unique character of Tarkovsky’s films. Of course everybody recognises the sounds of water, like a stream, and of raindrops, but the steps also sound symbolic to me.’ (RS, 2018)

Just as Sylvian did with ‘Maria’, Sakamoto responded musically to the final film by the master director. For the track ‘walker’, he describes, ‘basically, I recorded my footsteps walking around in a forest. That is directly connected to some scenes from The Sacrifice, which is my favourite Tarkovsky film, along with The Mirror.’ (2018)

The album async also includes Life, Life on which David Sylvian narrates the words of Andrei Tarkovsky’s poet father, Arseny Tarkovsky – a piece that I will return to on this site in future. For my playlist, I precede ‘Maria’ with ‘andata’ from async and follow it with ‘walker’, creating a trilogy of tracks from Sylvian and Sakamoto inspired by the work of the great Russian film-maker.

In 2018 I attended the premiere of the film Coda at the British Film Institute on the South Bank in London. Interviewed after the showing, Ryuichi was asked a question from the audience: ‘What is it about Tarkovsky’s film-making that inspires you?’ Sakamoto paused, still for a moment in thought, and said: ‘It’s a very complex subject to talk about, Tarkovsky and his films, of course. Because there could be so many aspects to talk about. His book is entitled Sculpting in Time, so he was very conscious about constructing something ‘in time’. And making something ‘in time’ is definitely something very musical. We musicians and composers always think about designing something, putting something, ‘in time’.’ Animated now, he’s using his hands as he enthusiastically describes the detail of a specific film-scene. ‘All the composition of those movements and sounds are constructed, made as a piece of music to me. All of his films are made in that way to me. It’s not that I get inspiration from images, or his imagination – well, I do, but also I can learn musical composition by looking at his films.’

‘Maria’

Ryuichi Sakamoto – treated piano, organ; David Sylvian – synths, tapes, vocal; David Torn – guitar loop

String arrangement by Ryuichi Sakamoto

Music and lyrics by David Sylvian. Arranged by David Sylvian.

Produced by Steve Nye, assisted by David Sylvian. From Secrets of the Beehive by David Sylvian, Virgin, 1987.

Lyrics © samadhisound publishing

Download links: ‘Maria’ (iTunes); ‘andata’ (iTunes); ‘walker’ (iTunes)

Physical media: Secrets of the Beehive (Amazon) ; async (Amazon)

Related: The Sacrifice (Amazon); Andrei Tarkovsky’s book Sculpting in Time (Amazon); Coda, Stephen Nomura Schible’s documentary on Ryuichi Sakamoto (Amazon)

The featured image is a still of the character Maria from The Sacrifice, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky (1986). All quotes from Tarkovsky are from Sculpting in Time, translated from the Russian and © Kitty Hunter-Blair.

Sources and acknowledgements for this article can be found here.

‘As I’ve been making music and trying to go deeper and deeper, I was finally able to understand what the Tarkovsky movies are about – how symphonic they are – it’s almost music. Not just the sounds – it’s a symphony of moving images and sounds. They are more complex than music.’ Ryuichi Sakamoto, 2018

More about Secrets of the Beehive:

The Devil’s Own

When Poets Dreamed of Angels

Let the Happiness In

Also from 1987:

Very nicely compiled, nuanced, and enjoyable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the feedback, Keith.

LikeLike

Wonderful! Informative and thought-provoking post about one of my favorite Sylvian tracks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful piece very informative and leading me to explore more of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s work as well as David’s. Always such interesting articles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A beautiful deconstruction of the dreamiest of songs. Fond memories of sitting in my car, parked up, heating full, drifting away to Maria!

Another great post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

david’s work has always utterly captivated me. this was a fascinating glimpse into the creative process that resulted in a song that subconsciously brings me to shallow breathing and stillness, such is its power. timeless art. thanks for sharing this article; new avenues to explore.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“I love the care and precision in the diction as those lines are delivered.”

And I loved the heartfelt simplicity of this line – as well as the whole article, as always

LikeLiked by 2 people

Heartfelt thanks for the comments, and thank you to everyone for being here.

LikeLike

A beautifully nuanced and revealing piece of one of Sylvian’s most overlooked treasures. I always wondered if one of the most arresting images from the song, Every Colour You Are was also inspired by the scene in this film where Alexander torches his house…’ and warmed his hands by fire…’

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Karl. You may well be right about the reference in ‘Every Colour..’.

LikeLike

Your blog means so much to me, the background informations are incredible. This one was the best so far, but they are all stunning. Thank you so much for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A sincere thank you for this feedback. I’m glad that you enjoy the articles.

LikeLiked by 1 person