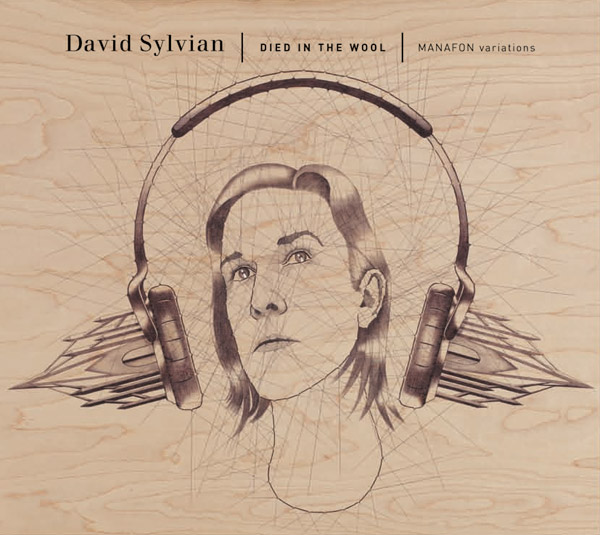

The vocal disc of David Sylvian’s 2011 album Died in the Wool comprises pieces that fall into three categories: variations on tracks from his Manafon album created by contemporary classical composer Dai Fujikura, Manafon variations crafted by Punkt festival founders Jan Bang and Erik Honoré, and six compositions appearing here for the first time.

‘A Certain Slant of Light’ is one of the new pieces and marks a novel creative approach for Sylvian – taking the words of a poet as lyrics and the starting point for developing a complementary composition.

The trigger for this was a commission that Christian Fennesz and Sylvian had received to set to music poetry by the nineteenth century American writer Emily Dickinson. This project most probably related to the Gustav Deutsch film Shirley: Visions of Reality which features another Died in the Wool track based on a Dickinson poem – ‘I Should Not Dare’ – as well as other music by Fennesz and two Sylvian tracks from Manafon. The movie was released later, in 2013, and brings alive thirteen paintings by the American artist Edward Hopper. Shirley, the protagonist, is first seen aboard a train in a recreation of Hopper’s painting Chair Car, reading a book of Emily Dickinson poems. Edward Hopper is said to have been absorbed by Dickinson’s writings.

Whatever the motivation, it’s easy to see why Emily Dickinson might be someone to whom Sylvian would be drawn – a reclusive figure, covertly devoted to her art, and who confronted in her writing some of the fundamental themes of human existence: faith and doubt, life and death. She had been a resident of Amherst, Massachusetts, just sixty miles from Sylvian’s then home in New Hampshire.

Born in December 1830 into a prominent Amherst family, Emily Dickinson lived in the town for her entire life, taking extended trips away on as little as a dozen occasions in all that time. She enjoyed a rich education at the Amherst Academy, studying subjects such as Philosophy, Geology, Latin and Botany, everything underpinned with a firm biblical foundation that saw natural order as an outworking of heavenly design. Neither she nor her sister Lavinia ever married, residing together in the home they had once shared with their parents. The extent to which Emily had been dedicated to writing poetry was only discovered by Lavinia after Emily’s death in 1886, and whilst a first selection was published in 1890, it wasn’t until 1955 that a complete edition was produced with the verse presented as it had been written rather than subject to edits or grammatical ‘correction’.

The sisters were brought up in a devout Christian home where daily religious observances were held. This was a time of Christian revivals in New England when many people felt a strong conviction to turn to God and commit their lives to Him. Some of those closest to Emily responded but she was never able to come to faith in the same way. Letters to her school friend Abiah Root pay testament to her spiritual struggles:

‘Dear A. upon the all important subject, to which you have so frequently & so affectionately called my attention in your letters. But I feel that I have not yet made my peace with God. I am still a s[tran]ger – to the delightful emotions which fill your heart. I have perfect confidence in God & his promises & yet I know not why, I feel that the world holds a predominant place in my affections. I do not feel that I could give up all for Christ, were I called to die. Pray for me Dear A. that I may yet enter into the kingdom, that there may be room left for me in the shining courts above.’

Letter from Emily Dickinson to Abiah Root, September 1846

A well-known later poem, written when Emily had eschewed church attendance, rejects formal religious observance but not the very existence of the deity. She hears God preaching in the sanctuary of the world around her, rather than in a church building:

‘Some keep the Sabbath going to Church –

I keep it, staying at Home –

With a Bobolink for a Chorister –

And an Orchard, for a Dome –

Some keep the Sabbath in Surplice –

I, just wear my Wings –

And instead of tolling the Bell, for Church,

Our little Sexton – sings.

God preaches, a noted Clergyman –

And the sermon is never long,

So instead of getting to Heaven, at last –

I’m going, all along.’

(A ‘Bobolink’ is a songbird)

‘A Certain Slant of Light’ showcases Sylvian’s new catalyst for composition and has a close thematic fit with his compositions of the time. The shadow of death and loss pervades much of Emily Dickinson’s work, and all the new tracks on Died in the Wool touch upon thoughts of the end of life and the significance of a life lived.

Elsewhere in Dickinson’s poetry the sound of a church organ is something which is captivating and mysteriously restorative:

‘I’ve heard an Organ talk, sometimes

In a Cathedral Aisle,

And understood no word it said –

Yet held my breath, the while –

And risen up – and gone away,

A more Berdardine Girl –

Yet – know not what was done to me

In that old Chapel Aisle.’

(‘Berdardine’ is probably a reference to a follower of St. Bernard, the founder of the Cistercian order, implying Dickinson had been drawn closer to God by her experience in the church that day.)

In ‘A Certain Slant of Light’ the sacred music heard at a place of worship recurs as an image but this time with no positive association. The light of the first line does not bring brightness and clarity as might be associated with a shaft of sunlight illuminating a dreary scene, rather it ‘oppresses, like the Heft/Of Cathedral Tunes’. It brings with it a hurt borne from heaven:

‘An imperial affliction

Sent us of the Air’

The poem speaks of internal pain, a ‘Despair’, the cause of which is no physical wound; the pain cannot be described but is so real that even the physical landscape takes notice as dark, silent shadows are cast by the light.

Sylvian’s vocal is front and centre as the track starts and I love his rendition of Dickinson’s words, the vibrato of his mature voice emphasising the emotion. The musical soundtrack is created by Jan Bang and Erik Honoré, their inventive use of electronics and samples building a sound-collage atmosphere with both texture and depth. They create a delicate, poignant pause in the accompaniment after the description of this hurt as being ‘…internal difference/Where the Meanings, are’: in the inner self, where we seek to make sense of our lives.

As the poem ends Bang and Honoré introduce the plaintive trumpet of Arve Henriksen, capturing the mood of Dickinson’s final couplet; as the sun sets on this winter afternoon, its distance from us is as great as that seen ‘On the look of Death’. Henriksen’s sensitive vibrato echoes that of Sylvian’s vocal. ‘We used samples of trumpeter Arve Henriksen extensively on the second part of the song,’ explain the sound sculptors. ‘These were taken from a live performance, resampled and improvised onto the track by Jan.’ (2011)

Sat on the floor of the Sørlandets art gallery in Kristiansand with maybe 150 other people on 1 September 2011 was the first time I witnessed Arve Henriksen playing the trumpet live. It was also my first visit to Norway and attendance at the Punkt festival. I was instantly drawn in by the evocative tone and delicacy of Arve’s playing. He seemed to caress the instrument with tender breaths, sometimes half-singing through the trumpet in an impossibly high falsetto. Ghostly, gentle, genuinely beautiful.

I’d been unconsciously aware of Arve’s work previously, in particular appreciating his contributions to the Nine Horses album Snow Borne Sorrow without ever realising that it was he who was playing. I’d also owned a copy of Cartography, his 2008 recording on ECM, since its release, but I’d mainly concentrated on the tracks featuring contributions from David Sylvian and was yet to appreciate fully what is now one of my all-time favourite albums. (See: ‘Before and Afterlife’.)

Having subsequently seen Arve play live in a number of different settings, I can picture him performing whenever I hear his distinctive sound – seated, eyes closed, a picture of concentration. He very worthily continues the tradition of trumpet/flugelhorn players who act as a foil to Sylvian’s vocal: Mark Isham, Kenny Wheeler, Jon Hassell, Harry Beckett, Arve Henriksen…

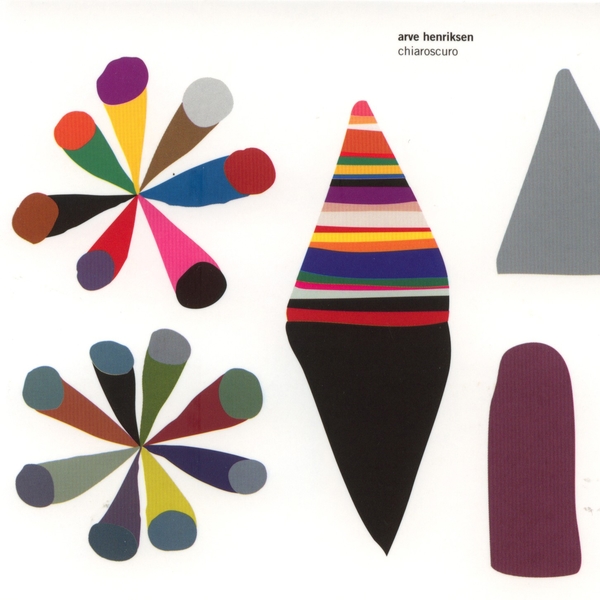

When I listen to ‘A Certain Slant of Light’ on my playlist, having been immersed in the sample of Arve’s playing used by Jan Bang and Erik Honoré in the final part of the song, I like to follow it with the track ‘Ending Image’ from Henriksen’s 2004 album Chiaroscuro. The album is produced by Jan and Erik and features their sampling and electronics skills as well as the drums and percussion of Audun Kleive who also appears on the Henriksen/Sylvian collaborations on Cartography.

Selecting a playlist of tracks for iTunes in 2009, David Sylvian included ‘Blue Silk’ from Chiaroscuro, commenting: ‘it’s hard to believe Arve wasn’t born with the trumpet attached to his lips. It’s rare to find a musician so utterly in tune with his instrument. And then there’s his voice.’

‘Ending Image’ is a short track, the heart-rending playing complementing ‘A Certain Slant of Light’ perfectly. It’s a time also to reflect on the dedication by Sylvian of ‘A Certain Slant…’ to M.K. – Mick Karn, his Japan and Rain Tree Crow bandmate and collaborator. A stripped back version of the track accompanied simply by acoustic guitar had appeared as a free download on davidsylvian.com in June 2010 with an invitation to make a donation to the ‘MKA’. Mick had been stricken with cancer and the Mick Karn Appeal was launched by friends to raise money to help fund his return for treatment from Cyprus to London.

Soon after the formative version of the song appeared online, Sylvian was asked about Karn. ‘As far as Mick’s illness is concerned, I feel terribly for him. We’re no longer close but there are people in life with whom you’re connected for a reason. We’ve fulfilled karmic duties in one another’s lives. In that sense, if in no other, he’s family and the relationship will no doubt continue to play itself out.

‘His illness has been protracted and involved considerable suffering, the kind you wouldn’t wish upon anyone. I wish him peace, something he appears to have known so little of in all the years I’ve known him. Peace and a haven from the inner demons that have plagued him throughout this lifetime.

‘If I could, I’d embrace him and remind him how much I’ve always loved him and in that instance, for the duration of the embrace if not a moment longer, he would know it to be true.’

Tragically, Mick Karn died on 4 January 2011.

‘A Certain Slant of Light’

Jan Bang – samples; Erik Honoré – synthesiser, samples; David Sylvian – vocals

Samples: Arve Henriksen – trumpet, Helge Sten – guitar

Music by David Sylvian, Jan Bang & Erik Honoré. Words by Emily Dickinson. Arranged by Jan Bang & Erik Honoré.

Produced by David Sylvian. From Died in the Wool, Samadhisound, 2011.

Emily Dickinson’s words © copyright The President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Download links: ‘A Certain Slant of Light’ (Apple); ‘Ending Image’ (Apple); ‘Blue Silk’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Died in the Wool (Amazon); Chiaroscuro (Amazon)

The version of the track posted in support of the Mick Karn Appeal can be downloaded at David Sylvian’s official website here.

The film Shirley: Visions of Reality is available for rent or download here.

This article was first published in June 2018 and subsequently updated in December 2022. Sources and acknowledgments can be found here.

Thank you to Alf Solbakken for permission to use his image of Arve Henriksen.

There’s a certain Slant of light,

Winter Afternoons –

That oppresses, like the Heft

Of Cathedral Tunes –

Heavenly Hurt, it gives us –

We can find no scar,

But internal difference –

Where the Meanings, are –

None may teach it – Any –

‘Tis the seal Despair –

An imperial affliction

Sent us of the Air –

When it comes, the Landscape listens –

Shadows – hold their breath –

When it goes, ’tis like the Distance

On the look of Death –

Emily Dickinson

More about collaborations with Jan Bang, Arve Henriksen & Erik Honoré:

Atom and Cell

Before and Afterlife

The God of Silence

Playing the Schoolhouse

More about Died in the Wool:

Lovely post. I saw Arve recently for the first time with Jan Bang, Erik Honere, and Eivind Aarset, a completely mind blowing evening.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks datz. Seeing these musicians perform really brings alive their craft, and afterwards I always hear new aspects when listening to tracks where they feature.

LikeLike

Time also, has to relate to distance, in the number of Earth orbits, since 1886 or since 2011. Plus 1 shortly, for 2022. Light is fundamental. Life and death are fundamental, to individuals, of all species. Now, I think of the latter more, as it has to be a fact, that (for me) many less years remain, than I have already lived. Without being morbid about it, this is a natural train of thought. Very many others will have thought and will think, about it,

“…internal difference where the meanings, are…”,

reminds me of my current cellular and physiological studies. This touched Mick and currently, it touches two members of our (my partner and I’s) respective families. Mutations in proteins and replication occur. They have to.

I will ask my partner about Emily Dickinson (as she is more literary than I). With Edward Hopper, she and I are on a more equal footing. Ditto with the work of David Sylvian and Mick Karn et al. They are and were, great at their chosen careers.

David Sylvian has bridged life and death, as far as can be done, in the skilful blending of 1 minute and 19 seconds of his music, to Emily’s words (written before at least eight billion people were alive). A tribute to his colleague and friend.

Only a site like this, and another skilful writer, could bring all these elements together. Thanks. All the best to all readers for the new Earth orbit of 2023 AD (after circa. 4.6 billion already, as far as science knows). J.

LikeLiked by 1 person