1988. Home with the vinyl in my hand. Plight & Premonition. First play. A quiet start – turn it up. Then jump out of my skin, startled by that vibrating, loud percussive alarm! Senses heightened now, like exploring unfamiliar territory, unsure of what will be discovered… dark, with occasional glimpses of light… ‘the spiralling of winter ghosts’ indeed.

Many times along the way a new release from David Sylvian has resulted in initial bewilderment. Exactly what is this music and where did it come from? Such was my experience on that day back in ’88. This time a collaboration with Holger Czukay of Can, following on from the contributions Holger had made to Brilliant Trees, Words with the Shaman and Steel Cathedrals. Recorded much earlier – long before any sessions for Secrets of the Beehive – but only now reaching the ears of the public.

‘Great things are not accomplished by those who yield to trends and fads and popular opinion’ (attributed to Jack Kerouac). Those words could have been written for these artists.

At the time of this release I was still most used to listening to music in five-minute parcels, architected with form and progression, with a beat or a vocal to capture the attention. ‘Plight’ is something else entirely. It takes you to another place, somewhere to experience through sound. One of the amazing things about the piece is that it is constructed with elements that are unique and other-worldly, yet they also seem organic and conjure an authentic sense of location.

We hear deep drones, single piano notes, tape hiss, distant voices, notes that build and ebb away. At one point a breathy flute melody appears like a firefly dancing in the half-light. There are bells, a crescendo of strings, then a train makes its way across the landscape rattling in its tracks. I can remember thinking, ‘nothing really happens,’ but on repeated listens I was captivated by what does happen.

Gazing at the beautiful cover photograph by Yuka Fujii only heightened the mysterious sense of place, with discarded cloth caught in fallen timber – an untold back-story captured in that image.

The serendipity in the creation of the album is a joy. ‘Holger Czukay and I were in constant contact during the ’80s, so to receive a request from him asking me to come to Köln when convenient wasn’t unusual,’ Sylvian recalled. ‘Specifically, I’d been asked by Holger to supply a vocal for ‘Music in the Air’, the final track on Rome Remains Rome, which was released in 1987. This places us back in the Winter of 1986. The night I arrived in Köln and drove on out to Can’s studio, Holger was in high spirits.

‘I’d arrived on a winter’s evening. I probably checked in the little, suitably depressing, pension a short walk from the studio and then we convened at Holger’s favourite restaurant where, as was custom at the time, I watched him consume a plateful of cooked meats while I picked at some bread, the only vegetarian option. We drank some wine, spoke of tomorrow’s recording, and then made our way to the studio.’

What sparked between Czukay, Sylvian and DJ/journalist Karl Lippegaus at the studio that night caused the intended project to be set aside for something else entirely. The following two nights were spent pursuing the ideas that surfaced. Then Sylvian’s time was up, so he departed without ever delivering that vocal.

Speaking very soon after leaving these first sessions, Sylvian was clearly inspired in Can’s abandoned-cinema studio; it was a space designed to trigger creation, and free from the ticking clock and climbing bill of a commercial set up. ‘Holger just tried to create an atmosphere in which Karl and myself would start to play, to perform. So we started just playing, and just played for hours all night…As Holger always says, he has built the studio for the artists and not for the engineer. So it works to your advantage. You just sit down and plug into something, and there’s instruments everywhere. And while you make a loop here with the guitar, you go over to the harmonium and you start playing, and you end up with this whole cycle of sounds going on. And you can’t pinpoint what they are, which is interesting. And Holger was also using short wave. Do you know, something very special came out. I felt something very special when I left.’ (1986)

In fact, to begin with it wasn’t even clear that the musical explorations were being captured at all. ‘I settled down at the harmonium, I think it was, and unbeknownst to me Holger put the machines into record…As the evening went on I recorded a series of improvisations on a number of instruments. It became clear as the work progressed that there should be little in the way of “performance”, that the work should sound as though it’d been captured illicitly while the instruments themselves reverberated in that large room. Holger made a point of recording me in the process of finding myself on any given instrument. At the point that I felt I had developed something worthy of recording, the moment had already passed and we’d move on.’ (2010)

Czukay’s use of short-wave radio and dictaphone introduce ‘found’ voices and musical snippets to the piece, adding to the aura of this unfamiliar but authentic environment. The techniques date from some of his earliest creative experiments following time under the tutelage of Karlheinz Stockhausen and they inspired his imagination for future projects.

‘A short-wave radio is just basically an unpredictable synthesiser,’ Holger would assert. ‘You don’t know what it’s going to bring from one moment to the next. It surprises you all the time and you have to react spontaneously. The idea came from Stockhausen again. He made a piece called ‘Short Wave’ [‘Kurzwellen’]. And I could hear that the musicians were searching for music, for stations or whatever, and he was sitting in the middle of it all and the sounds came into his hands and he made music out of it. He was mixing it live – and composing it live. He had a kind of plan, but didn’t know what the plan would bring him. With Can, I would mix stuff in with what the rest of the band were playing. Also, we were searching for a singer and we didn’t find one – we tested many, but couldn’t find anyone – so I thought, “Why not look to the radio for someone instead? The man inside the radio does not hear us, but we hear him.”’ (2009)

Sylvian has described ‘Plight’ as more Holger’s track, given that Czukay continued to develop it for some months after recording, as opposed to ‘Premonition’ which is more his own and stands much closer to the first recorded take. ‘Plight’, he says, ‘didn’t stand up as a finished work at the time of my departure.’

‘That piece I think was about an eight-minute piece of music which he worked on for about six months: editing, on and off. And I think he transformed it completely because the original piece doesn’t have the, I don’t know what the right word would be, kind of potency of the piece that he produced out of it. It has a very strong atmosphere, even though very little is going on.’

Notable are edits that radically change the flow. ‘He has a totally idiosyncratic approach to technology, and the way he handles tape and so on would frighten most engineers and producers because he really plays with it…he’s very radical with the editing, he’s straight in there and cutting up these mixes with no sense of preciousness about the master or whatever. In that way he takes risks and comes up with more amazing results because of that.

‘The cuts, as radical as they are, really appeal to me…they create the shift in perspective in your mind, because it’s the kind of music that creates visual images in the mind. I found that when I was listening to it, these cuts worked in the same way as edits in film did for shifting perspective, or complete cut away to another location of image in the mind. And again nobody else would have, I think, taken the risk of leaving edits in in the way that Holger did.’ (1989)

The crafting of the piece involved adding more samples (‘a minor piano motif, a flute sample, etc’) and was part of Czukay’s familiar methodology of recording quickly only to spend inordinately longer developing the mix.

‘Holger himself would edit and rework his own material for extremely long durations. He frequently said the tracks or sketches he’d been working on would reach a stage in their development that necessitated their temporary retirement, at which time he’d file them away, “let them mature like wine”, only later taking the tapes from the stacked shelves, bringing them into play. A means of forgetting context and content perhaps. Memories of evocations tied to uncertainties. I’m sure this is how some of the orchestral samples in both ‘Plight’ and ‘Premonition’ were created. He’d brought them out of the “wine cellar”, into the light, for just this purpose.’

What’s certain is that both these tracks have their roots firmly in improvisation. Sylvian’s career is marked by a continual desire to embrace this approach to creating music, whether it be a solo within a song structure or an extended non-linear instrumental. Plight & Premonition is a milestone album in the exploration.

Listening to ‘Plight’ now, the bewilderment of thirty years ago is gone but it retains all of its potency. Familiarity takes away none of the mystery implied in the track’s subtitle, ‘the spiralling of winter ghosts’. ‘We’d happened upon a form of composition that gave the impression that the sounds had been created while we were absent by instruments abandoned to the earth and the woods, sounded by the coarse winter elements. Or, the unanticipated impression on listening back to the work was that there was no one person dictating the direction of the pieces, as if the sounds on tape were created by the ghosts of the instruments themselves.’

The title of the track may well have been inspired by a work by Joseph Beuys, an artist for whom Sylvian held a deep fascination (see ‘The Healing Place‘). Beuys’ Plight installation was first staged at the Anthony d’Offay gallery in central London in the Autumn of 1985. It consisted of two rooms that were lined with vertically positioned rolls of felt. The material held the heat within the room and deadened the sound. In the midst of this strange acoustic environment stood a grand piano, closed, its silence emphasised by a board laid across the lid displaying blank musical staves. Perhaps there is a parallel between Sylvian’s description of his album with Czukay being played by the instruments themselves or directed by some outside force, and the sense in Beuys’ installation that the soundtrack to the visual art was generated by nothing other than the movement of visitors through the space he had created.

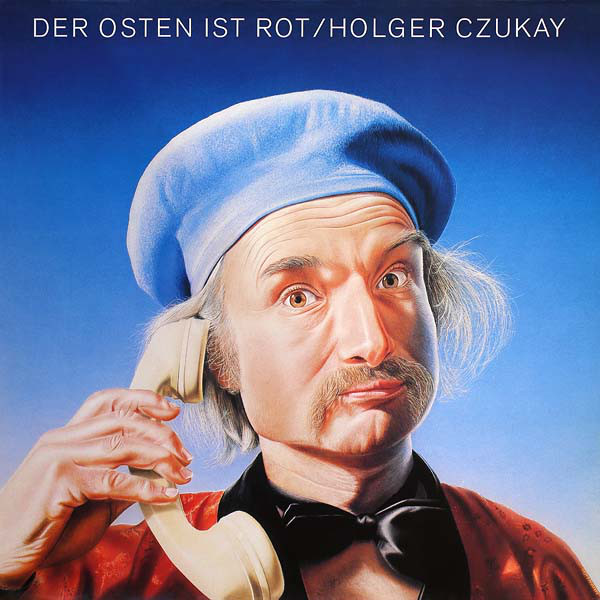

Whilst some of Holger’s solo work veers perilously close to the zany, there are truly lovely pieces to be discovered. On my playlist I follow ‘Plight’ with ‘Träum Mal Wieder’ from the album Der Osten ist Rot, released by Virgin in 1984. Where the Sylvian & Czukay instrumental is beatless, ‘Träum Mal Wieder’ has an odd industrial rhythm, like the turning of a printing press or a mechanical loom. Around this are layers of found voices and Holger’s distinctive guitar work. Each new listen reveals more nuance and the short-wave voices become familiar friends. ‘Träum Mal Wieder’ features Can’s Jaki Liebezeit who is credited on Der Osten ist Rot with playing drums, harmonium, trumpet, piano and organ. Jaki also appears on Plight & Premonition.

‘Träum mal wieder’ translates from German as ‘dream again’. The world lost a special talent when Holger passed away in 2017. Keep dreaming, Holger… keep dreaming.

‘Plight (the spiralling of winter ghosts)’

Holger Czukay – radio, organ, sampled piano, orchestral and environmental treatments; Jaki Liebezeit – infra-sound; Karl Lippegaus – radio tuning; David Sylvian – piano, prepared piano, harmonium, vibes, synthesisers, guitar

Mixed and processed by Holger Czukay

Produced by Holger Czukay. From Plight & Premonition, Venture, 1988

Recorded at Can Studios, Köln, West Germany 1986-7

All David Sylvian quotes are from articles in 2018 unless otherwise indicated. Full sources and acknowledgments can be found here. Originally published in May 2018 and subsequently revised and expanded in June 2021.

Download links: ‘Träum Mal Wieder’ (iTunes)

Physical media links: ‘Träum Mal Wieder’ (as part of the Cinema box-set) (Amazon)

David Sylvian’s 2002 remix of Plight & Premonition was re-released on Grönland Records in 2018, together with the later collaboration Flux & Mutability. Issued on digital download, vinyl and cd (Grönland) (Amazon – cd) (burningshed – vinyl) (burningshed – cd)

A video of the Plight installation by Joseph Beuys can be viewed here.

‘The general idea was not to perform as such, it was to do as little as possible. To generate music with as little, as minimum performance as possible so it’s almost like it generates itself, so the finished result is very organic. It was very strange.’ David Sylvian, 1986

More about work with Holger Czukay:

Fascinating! I recall a similar experience buying Plight. It really got me into ambient music. At the time I didn’t think it strange that Sylvian had produced this work, I just accepted it. Looking back it was quite a departure even from words with the shaman!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe a comment on a small detail in the credits: Holger’s Can Studio was not in Cologne (as it is often referred to), it is in a small town called Weilerswist which is a rough 30 km outside of Cologne. Apart from that – I really enjoy reading all these articles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the insight, Peter.

LikeLike