Early in the 2000s, Charles Lindsay hit upon an innovative approach to the creation of photographic images that would transform his artistic work, and, without exaggeration, alter the course of his life. The techniques he used were grounded equally in his scientific education and aesthetic sensibilities as an artist. He created pictures that captured the imagination both of academics and fellow artists, leading him into collaborations with individuals from both disciplines – including David Sylvian and Steve Jansen.

Lindsay trained as a geologist, visiting the Arctic as a student to obtain relevant work experience which would also help to fund his studies. Living in Canada from a young age he grew up immersed in the grandeur of the natural world – but the Arctic was unlike anything else. The environment he encountered there made a lasting impression on the young man. ‘It was my first exposure to vast, tree-less, human-less landscapes. And that was really exciting to me. It was also the beginnings of photography for me, and the camera became the lens through which I experienced the world.’

Both his formal education and his travels engendered a true fascination with the depths of time. ‘I split after school, and I’ve always been interested in our deep evolutionary past. I’m also a big outdoors guy. I went to Indonesia, and I was trying to go and live with a tribe of people – a hunting tribe – that were as primitive as I could find… I’m talking about the mid-eighties… and those tribes are few and far between on the planet.’ He ended up spending two months every year for eight years with the Mentawai, one of the oldest tribes in Indonesia who live a hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the coastal and rainforest environs of their island home. There he befriended a particular shaman and witnessed first-hand the ritual ceremonies and community life of the animist people, including rites of initiation, healing, and hunting with poisoned arrows. Charles chronicled these incredible experiences through the camera lens, publishing Mentawai Shaman: Keeper of the Rainforest with APERTURE in 1992.

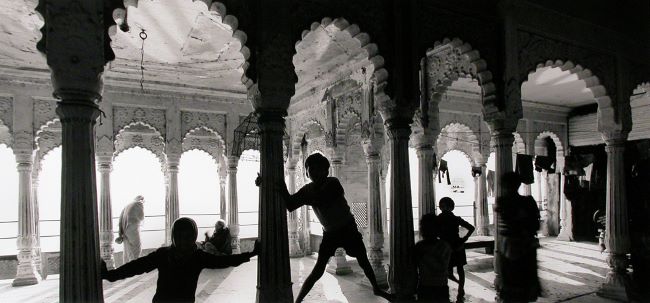

There followed time in Bali, investigating a complex and savage relationship between man and the natural world which results in the capture of green turtles to be sacrificed in ‘religious rituals linking three different belief systems: Hinduism, Islam and Chinese merchants.’ Then to India, creating black and white panoramas portraying the architectural splendour and vibrant chaos of life there as if in a Shakespearean street drama.

As the new millennium dawned, the strangest of experiments would lead Charles to explore some familiar themes through abstract rather than representational images. ‘I was experimenting with contact printing and various types of camera-less photography,’ he recalls, ‘it was really a form of play. It’s an area that’s well trod; I wasn’t thinking I was going to find that much. But I was in an industrial building and on the glass plate where the safety inspector marks whether the elevator is safe or not, there were a couple of generations of spray-painted graffiti and that glass plate was hanging by one screw. I took out that piece of glass – it was about eight by ten inches, something like that – I took it back to my dark room and I contact printed it. And what I saw was that the paint that looked two dimensional on glass became three-dimensional through the translation of photogram. Black became white and vice versa. So, the dimensionality of the image was what woke me up to this idea, this process.

‘I then went out and worked with many forms of clear back or base, and many forms of emulsions, liquids with pigments and all kinds of things. The one I settled on is carbon-based, it’s not silver as traditional photographic chemistry is. The carbon is super-fine, it has incredible tonal scale. I’m working with it on large pieces of a clear base, doing a number of things with it.’

Not being well-versed in such intricacies, Charles explained to me that a photogram is a photographic image made without a camera. Instead, objects – in this case a transparent base with traces of carbon manipulated upon its surface – are placed directly onto the surface of a light-sensitive material. Man Ray’s innovations in the method were the inspiration for Charles’ own experiments and the evolution of his own approach. Adam Fuss, a friend of Lindsay’s, was also an important influence; Fuss’s colour photograms in particular.

‘The process involves evaporation, it also involves electro-magnetism. I’m often clipping a battery charger at one end or the other of the base; it affects the charge that’s running across the material and how the material itself gathers. So it’s definitely mad chemistry. As far as what creates the images, it’s both accident and my manipulation. The real breakthrough I felt was when I started to scan these negatives at high resolution to make digital prints. The scan turned up a lot of information, it revealed information in that negative that traditional silver photography and traditional enlarging wasn’t. It also gave me a lot more control over contrast and tone.’

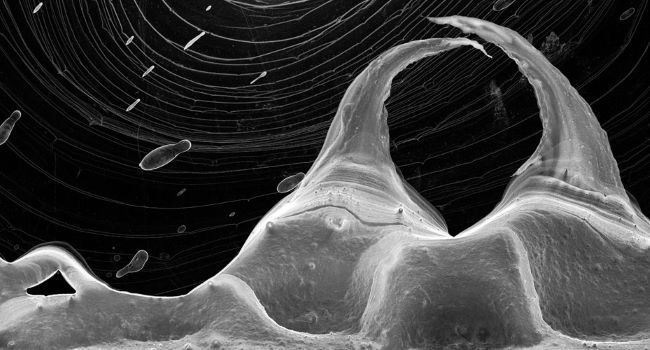

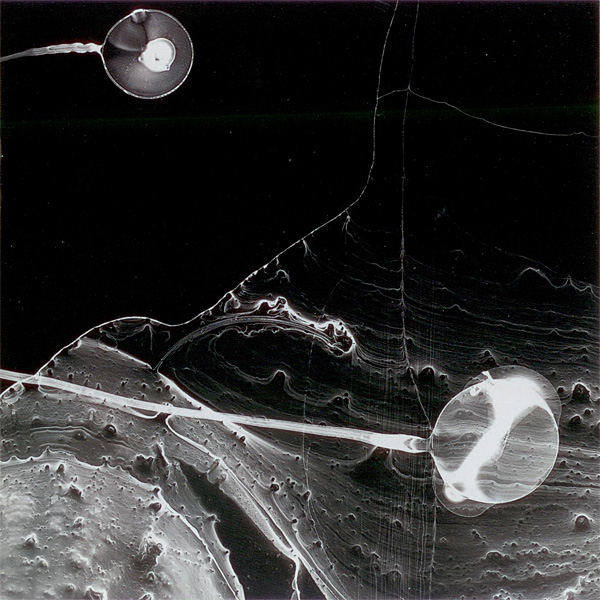

The results totally arrest the viewer’s attention in that they could equally be interpreted as depicting vast areas of deep space, or hugely magnified images of microscopic objects or organisms – ‘spatial ambiguities.’ I think it’s something about the fine detail as well as the forms represented that prompts this response. One thing is certain: they look absolutely real.

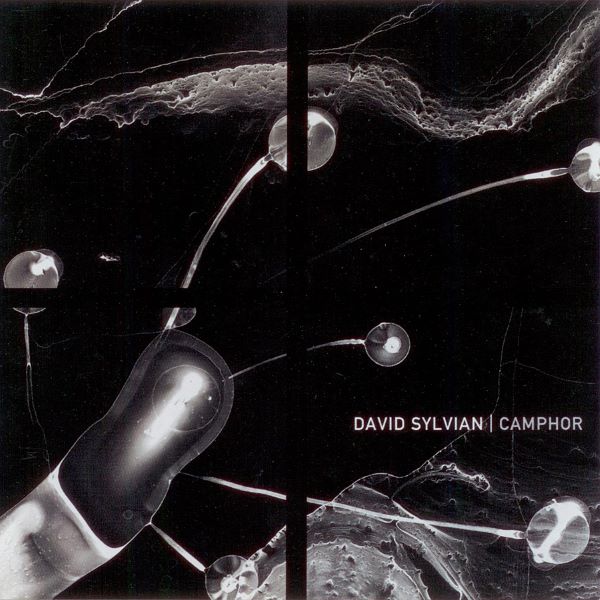

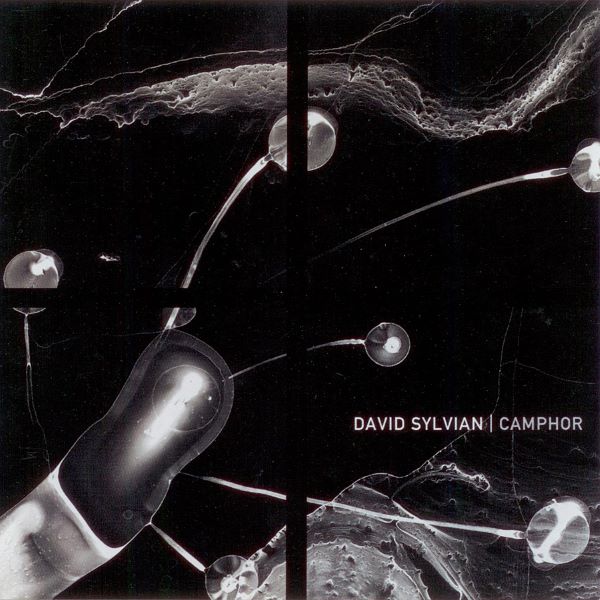

Lindsay’s pictures were soon being featured in the specialist press and reached an appreciative audience. ‘If I’m not mistaken David Sylvian first saw my work in the photographic periodical BLIND SPOT and approached me for artwork for the Camphor double CD package,’ Charles recalls. Many of us will remember picking up the instrumental retrospective when it was released in 2002, and contrasting the imagery it carried with Shinya Fujiwara’s bizarre eye-browed dog on the vocal companion piece, Everything and Nothing.

There was something of a commonality of purpose between the visuals and music. David Sylvian creates such lucid, organic environments in his instrumental work and the photographer has a similar intent. ‘I like to create worlds,’ Charles told me. ‘The photograph alone, sitting framed in a white space where viewers whisper, is not very satisfying to me.’

‘I’d prefer not to talk so much about process but for people to look at the pictures and think about other worlds. I like to think about what comes before and after humans and what’s outside of ourselves, and outside of our planet. It’s an amazing time through science – the images through the Hubble telescope – it’s a time to think about these things.’

At this early stage the work was presented under the name Science Fiction, encapsulating how the pieces work at the intersect between scientific discipline and the power of imagination. The physical presentation of the work was important and needed to be true to the vision of reaching beyond the ‘framed white space.’ Movement and music were called upon to inject dynamism. Having been invited to contribute to Camphor, it was Charles’ opportunity to return the compliment. ‘I animated the work and asked David to collaborate with me on sound for the short videos. He and Steve did a very good job of that.’ I wondered whether the pieces were excerpts from a longer composition created to be played in an installation space displaying the pictures, but Charles confirms not. The music was ‘specifically composed for the videos,’ so was conceived to match these exact images and movements. Lindsay was keen that the musicians responded spontaneously to the visual stimulus. ‘I did not guide. What they provided was spot on.’

The two short videos – ‘Science Fiction 1 & 2’ – were later posted on Sylvian’s official website and that of samadhisound, making available these two instrumental compositions by Sylvian and Jansen for the first time. The video was at a low resolution which suited the capability of the internet bandwidth of the time rather than the hyper-resolution of the photographer’s work, but it was great to hear how the duo matched processed electronics, radio, bowed cymbals and percussion to enhance the experience of entering the far reaches of the universe through one’s imagination. The work comes from a fascinating period when the samadhisound studio in New Hampshire was being put together and the capabilities of new technology were being tested out. The sound ideas here are part of the melting pot from which Sylvian developed Blemish the following year.

The video presentations featured in the early exhibitions of the work, and were available on a crazily limited DVD sold onsite. Charles confirms that the DVD contained no other contributions from Sylvian and Jansen, the two pieces being the extent of their work together.

Fortunately, Charles later posted the videos in HD quality on his vimeo channel, and they are presented below, now carrying the titles ‘Carbon I & II’, but otherwise unchanged.

‘My interest in abstraction is coming out in imagery, but I’m also interested very much in abstract music…I’ve always been interested in abstraction…I like making images and I like thinking in a way that while it’s made by humans, it’s not human-centric.’

Working with David and Steve was an important part of the evolution of the project, and led Charles to consider the creation of sound as being fundamental to his own art. ‘I loved it. It’s as a thrill to be collaborating with such talents. They visited my studio at that time. A lovely encounter on what was a very foggy day.

‘Shortly after that I went deep with sound/electronic music on my own, such that since then I’ve done all my own soundtracks. That seemed a more “true” way to create my art — but that’s not a hard and fast rule.’

The change of title from Science Fiction to Carbon reflected the artist’s developing thoughts about the connection between the methods employed to create such stunning pictures and the visceral response of the audience. Writing in Lindsay’s 2016 monogram dedicated to this series, astronomer Dr Jill Tarter comments:

‘Carbon is the fourth most abundant element in the universe (after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen). It controls the chemistry of life as we know it, and scientists argue that it is also likely to control the chemistry of any life that may exist beyond Earth…what enables the splendid diversity of microscopic and macroscopic life on this planet was manufactured deep within the nuclear furnaces of massive stars many billions of years ago.

‘Those stars exploded at the end of their lives, seeding the cosmos with the chemical building blocks of life. We are, in the truest sense, all made of “starstuff,” as Carl Sagan used to remind us.

‘So imagine what would happen on another world, circling a star other than the Sun. Would life evolve there? Would it be carbon based? Can we envision it in the depths of Charles Lindsay’s art?’

And there are still more angles to be explored. ‘Carbon is also fundamental to ink drawing and calligraphy,’ Lindsay enthuses, ‘one of the most ancient art forms, first developed in China. There are mines in Anhui Province specifically for art-grade carbon. I intend to go there post Covid.’

From those first experiments not long after the turn of the new millennium, pursuing the concept has clearly been absorbing. ‘The process always surprises me. There is something inherent in abstract work being so highly resolved, so “real”, that is completely compelling. They scale well, and animate too, as in the videos which David Sylvian and Steve Jansen made the sound tracks for.’

As photographic processing software and digital printing capabilities have advanced, so the work can be presented at a scale to envelop its observer. Below is a concept video for an installation of Carbon, which was largely realised at The Dennos Museum in Traverse City, Michigan in 2009. It’s accompanied by a unique mix of David and Steve’s music:

So, how did this project change Charles Lindsay’s life? On a single day in 2010 the photographer was bestowed with a Guggenheim Fellowship to pursue this work and he also met Dr Jill Tarter, the astronomer whose words are quoted above, introducing her to his abstract creations. ‘It was this other worldly, unknowable quality that led Jill Tarter to invite me to be the first artist in residence at the SETI Institute.’

The SETI institute is a research organisation whose mission is to explore, understand, and explain the origin of life in the universe, and to apply the knowledge gained to inspire and guide present and future generations. SETI stands for the ‘search for extraterrestrial intelligence’, and as a contractor to NASA the institute is engaged in monitoring for signs of transmissions from civilisations on other planets.

What followed was an extended period leading the institute’s arts programme. Artists and scientists working alongside one another, with the cross-pollination of ideas and techniques. Not parallel disciplines with incompatible world-views, but passions united in exploring possibilities that are beyond our human experience.

Looking back over Charles’ work, I was curious whether he discussed his time with the Mentawai with David Sylvian, given David’s repeated reference to the shaman as symbol of the musician or artist in society? ‘Yes, of course, we spoke about many things in the spiritual realm: we are both influenced by the heritage of India and Japan, among others. I’m more naturally comfortable in big nature, alone, and that would include the use of psychedelics. David and I never actually spoke about the pharmacological territory.

‘In 2004 we met in Japan, on Naoshima Island, where David was creating a sound installation. Another connection we shared was that I studied guitar with Robert Fripp at Guitar Craft in Spain. That’s another entire chapter… very interesting monastic practice.’

At the time of writing, there is another dramatic diversion in the creative life of Charles Lindsay. Stranded in Japan due to sudden Covid-19 travel restrictions, he holed up in Kyoto to see out the lockdown. Connections were made and imagination was sparked. ‘I’m so nomadic… and in fact selling my studio in New York state’s Catskill region right now, in order to move to Kyoto for an installation at Kenninji Zen Temple and a professorial position at Kyoto University of the Arts. On we go.

‘Carbon always struck me as fossils of the very near past. I was trained as an exploration geologist, so this is not simply hyperbole — I see the world in vast, and nano, time scales.’

‘Science Fiction I & II’

David Sylvian and Steve Jansen – all instruments

Music by David Sylvian and Steve Jansen

From Science Fiction 1 & 2, videos by Charles Lindsay, 2002

Video editing by Liron Unreich

Grateful thanks to Charles Lindsay for his participation in this article. Please do check out Charles’ website (http://www.charleslindsay.com/) and vimeo channel (https://vimeo.com/charleslindsay).

In a very recently released interview with Charles in the Artist Depiction series he talks about Carbon – view this segment here, or the whole 30 minute programme here.

The excellent book Carbon containing many photographs from this series can be obtained from the publisher, Minor Matters.

Full sources and acknowledgements for this article can be found here.

‘CARBON is a creation of fictitious worlds, drawing on my interest in the aesthetics of space exploration, microscopic discovery and abstract symbols. I am intrigued by the idea that so much of our expanding scientific knowledge is based on images from beyond our body’s normal scope of vision. I am also interested in the challenge and implications of comprehending our relative scale within the universe.’ Charles Lindsay, 2009

More about Camphor:

Why do you think the world deserves such an incredible, singular piece of writing/reportage? Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Outstanding piece on a very interesting individual, irrespective of links to DS – Bravo!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Science, art and music comprise a significant ‘chunk’ of my interests. In fact, I am studying the former at the moment as a v. mature student (third year). English and words also exert a very strong ‘draw’ upon me and I agree with Jas and Alasdair about the quality of your feature, vistablogger. Whilst the art work is abstract, to part quote Bryan Ferry, it is ‘…part true, part false, like anything…(from For Your Pleasure, Roxy Music, 1973). It (one image) could be a landscape from a high up orbiter, another part could be the micro inside part of a body magnified thousands of times. It could be physiological or just an object of the imagination. When Sigmund Freud said art had no purpose he was referring only to a direct purpose. He saw its value in sublimation. It’s what we see in it and what we feel from it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting to read some of the background – especially the link with Fripp and Naoshima!

I am fortunate to own one of the original Carbon photos, as well as the hardback book. The photo is exquisite – it is hard to convey the appearance, size, calmness and eerieness which somehow keeps grabbing you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was fascinated to discover how small some of the original pieces are, which are then reproduced at much larger scale in high definition. It really is incredible that so much fine detail is revealed. As Charles has said, our brains are programmed to read ‘high definition’ as ‘real’, giving that sense that you describe.

LikeLike

Fascinating stuff! As I’ve said before elsewhere, you should collect all these articles and publish them in a physical book. I’m sure there would be great interest in such a book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the thoughts and comments left here. Always read, always appreciated.

LikeLike

Just want to add my voice and thank you for all of your posts , but those two videos (particularly the soundtracks) shone for me. Would never have found them otherwise.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your blog, sir! I’m really grateful to you. It’s such a pleasure to read your writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person