Brief airy atmospherics and then immediately, the voice.

‘Running like a horse between the trees

The ground beneath my feet

Gives me something to hold onto’

‘Laughter and Forgetting’ picks up from the theme of the song ‘Brilliant Trees’. Here, though, joy and optimism are more unreserved. ‘Brilliant Trees’ captures the faltering of conventional religious faith, yet transforming love is found in another’s eyes. In ‘Laughter and Forgetting’ the sense of loss is not so acute as Sylvian again uses imagery from nature to express a joie de vivre that I find uplifting and alluring.

The songwriter could sense the progression. ‘This has been a period of self discovery. The darker things are understood now. ‘Ghosts’ was somebody lost, ‘Brilliant Trees’ was on the point of learning how to cope with those things and really begin to enjoy life. This album is more positive, yes.’

In my mind’s eye the horse is cantering through the woodland with sun streaming through the branches and dappling the ground, throwing back its mane as it weaves amongst the tree trunks in search of a pathway. It’s such an evocative image of liberation and of pleasure taken in simply being alive. The ‘ground beneath my feet’ recalls the phrase ‘leading my life back to the soil’ in ‘Brilliant Trees’. Here the earth is not a haven in the absence of a relationship with the celestial, but a source of strength and certainty in itself.

The equine image develops as a metaphor for the singer, who experiences freedom whilst being directed in a way that opens up the wonder of life:

‘With the reins around my heart

Guided by hands that spread life before my very eyes’

…new horizons revealed through love.

In later years, Sylvian has suggested that living without hope is potentially a positive mindset to adopt. That is to say, not longing for a point in the future when all will be good and life can be savoured, but rather enjoying today in all its fullness. ‘“To live without hope is to live in the present.” I’d begun to consider what it means to dwell in a state of hopelessness. That is, to attempt to live without submitting to the impulse to project possible outcomes resulting from one’s actions. To work fully committed to the present moment, to seek solutions, to treat others with dignity and compassion whatever the circumstances. Hope does tend to get in the way in this respect as it takes you out of the present towards an idealised or preferred outcome. Or, if a better outcome isn’t imaginable, if the situation appears without merit, it can lead to inertia, inaction. To live without hope but without a loss of love for, and commitment to life this, it seems to me, is perhaps a good place from which to start.’ (DS, 2009)

There are echoes of this world view in:

‘Well every hope falls down on its knees in time

But I’m no longer lost

Every day, every second, every hour inside

Love’s my only guide’

These lines start with a beautifully ambiguous phrase – possible interpretations being ‘all hope fails in time’, or ‘all human hope gives way to prayer eventually’. Either way, the fulfilment in the present is unequivocal.

The ‘God-given fields’, mountains, seas, rivers and shores of Gone to Earth hint at pantheism, so this guiding love could equally be that bestowed by another person or by the divine, as expressed through the splendour of nature.

‘Are these the years for laughter and forgetting?’

Sylvian has often weaved references from literature and cinema into his own compositions, borrowing phrases that resonate with his own thinking and express succinctly an image or emotion. Here the reference is to the title of Czech novelist Milan Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. I don’t read any direct parallels with that book, but rather words quoted that perfectly capture a sense of living with freedom in the moment, unburdened by the weight of the past.

Acknowledging the appropriation of Kundera’s title to radio host Alan Bangs, Sylvian explained how other art forms influence his own creativity. ‘It tends to be that you take in so much information and suddenly you find it surfacing in the composition. somehow… I tend to use titles a lot from other mediums like film, like literature. That’s a personal reference to something. That’s to say that something about that film, that book or whatever, helped bring out the nature of this piece of music. But it’s never really solely derived from a film or a book. Never, never. It’s from personal experience. But something from the film, or something from the book, just helped tip the balance and helped the ideas to flow.’

It is significant that there is ‘forgetting’ to be done. In order to laugh, one has to consciously leave behind past experiences that could overshadow the present. Sylvian: ‘“Laughter” isn’t a reference to outright laughter, but to an enjoyment of life in its most noble sense. Not your life, but life in itself. “Forgetting” means…not to take things too seriously. Not to take yourself too seriously. To dig behind…to move away from a past or segments of a past you find it difficult to move away from – but in a positive way. That’s the best explanation I can give, but it has many more levels than that.’

The uplifting feel of the piece had not been Sylvian’s original intention. ‘Actually, ‘Laughter and Forgetting’ started out as ironic… When I finished the piece, it just seemed so positive. And whenever I listened to it, I felt positive about it. So I obviously fooled myself when I was writing it. It’s a very positive piece of music.’ (DS, 1987)

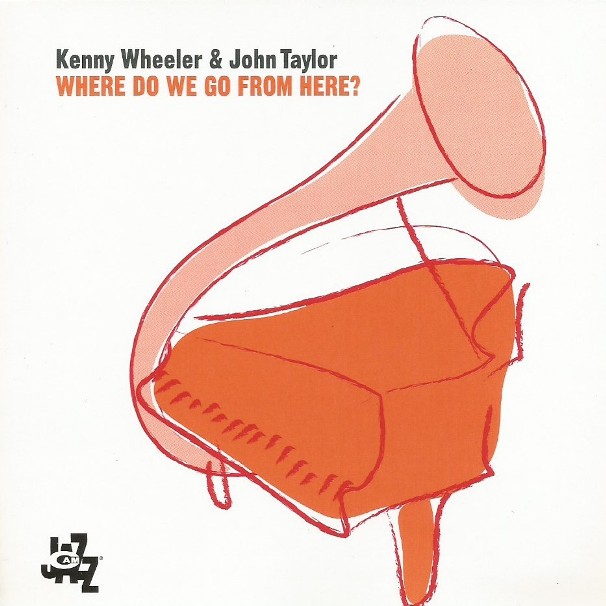

The music that follows beautifully extends the sense of release in the interplay between the piano of John Taylor and flugelhorn of Kenny Wheeler. Rather than share musical phrases, the duo engage in a melodic dialogue – responding to one another with perfect pacing and such a lightness of touch. It’s a chemistry that is all the more impressive in the knowledge that, whilst they had known one another and performed together for many years, their contributions were individually recorded for the song.

‘Kenny and I played on separate occasions,’ John later recalled, ‘we never met during this record. Maybe that’s the way David wanted to record because he didn’t like the recording situation.’ The session came together quickly. ‘‘Laughter and Forgetting’ wasn’t that long because we tried a few other ideas but there were only a few,’ the atmosphere created in the studio being ‘very comfortable. It’s nice to be treated that way.’ (JT, 1992)

Speaking just after the release of Gone to Earth, Sylvian explained how he had come to appreciate Kenny Wheeler’s playing: ‘When I first started living with Yuka, she introduced me to jazz music which I hadn’t really listened to. It’s so very difficult to get into jazz without somebody to help you. You need your way in, because there are so many paths to follow and it’s very difficult to find what’s right for you, I think. Yuka’s got a wide taste in jazz, and I began to pick up things that she would be playing in the house, and Kenny was one of those people…I tended to like the melodic quality of his playing. It’s a kind of smoothness and it’s very rich in quality and a melancholic feel which is really beautiful, which I haven’t heard in many trumpet players. It’s kind of purity of tone.’

The experience of working in the studio with Wheeler was also positive. ‘When I met Kenny, I was really surprised at his nature and his character…I met this very quiet, very shy man. I was really surprised and very pleased. The passion that he puts into his work… watching him playing in the studio, there is a quality of character he has that I really appreciate.’ Sylvian was particularly impressed with his attentiveness in achieving the right outcome for a song, even if he wasn’t convinced that Kenny truly comprehended the work to which he was contributing: ‘The feeling I like from him is that he is a perfectionist and he won’t let go – he won’t come in and think, “well this is an easy way of making £200 for a couple of hours,” or something like that, as a lot of jazz sessions musicians do, which I find very disappointing. But he doesn’t, he comes in and he has a standard of his own which he won’t let go, and he’ll keep on working until he has got something that he’s happy with, and I appreciate that way of working, even if I know that he doesn’t really understand what I am doing musically.’

It’s so sad that both Kenny and John Taylor have passed away in recent years. A joint album of earlier recordings was prepared for release in 2015, soon after Kenny’s death (On the Way to Two). In the sleeve notes John wrote touchingly, ‘it was a pleasure and joy to play with you for most of my life and I wish you were here now to listen to this music again with me.’ By the time the album was out, John had also passed having suffered a heart attack while performing at the Saveurs Jazz Festival in France.

It must have been late in 1986 or early in 1987 that, inspired by the interplay between these musicians on ‘Laughter and Forgetting’, I made for the 100 Club in London’s Oxford Street where the pair were due to perform in a small jazz ensemble. The venue will be known to some as the home to parties organised by the fanzine Bamboo. The club itself is situated below ground level, and as my friend and I descended the steps we saw a handwritten notice announcing that Kenny Wheeler would not be able to perform. Money was tight in those student days: should we still go in? We did, and I’m very glad of that decision because this was the most intimate venue in which I would hear John Taylor play. He was such an unassuming character, in fact my friend mistook him for a roadie.

We were seated to the left of the stage and beside John’s piano. I can still vividly recall the atmosphere as the musicians bounced off another in performance. I’m pretty sure there were five on stage, a drummer, double bass, two woodwind and John himself. My live music diet to then had been ’80s bands and Bowie – this was something new and I was fascinated by it. John’s shock of curly hair was animated as he delivered flourishes of melody from those piano keys. A formative musical experience. Later I was fortunate to hear Kenny live on a number of occasions, although never at such close quarters.

Over fifteen years later, I was thrilled to discover the album Where Do We Go from Here? by Kenny Wheeler and John Taylor. It was released in 2004 – long after Gone to Earth – but nevertheless the track ‘Fordor’ sounds to me like an unreleased sister session to that for ‘Laughter and Forgetting’. If you enjoy the duo’s work with David Sylvian, I would really encourage you to seek out this piece of music. The empathy that each player demonstrates for the other is extraordinary, Taylor’s crisp piano-work complementing Wheeler’s poignant and thoughtful flugelhorn. This is not showy jazz playing where speed of technique is displayed for its own sake, rather we hear two players who know one another’s sensibility and range, creating a mood through a clarity of tone and judgement of pace and rhythm that is a joy to experience. As the last sustained notes are dampened, I can only be glad that we have their recordings as a lasting legacy.

‘Laughter and Forgetting’

David Sylvian – vocals, atmospherics; John Taylor – piano; Kenny Wheeler – flugelhorn

Music and lyrics by David Sylvian

Produced by David Sylvian and Steve Nye. From Gone to Earth by David Sylvian, Virgin, 1986.

Recorded in London and Oxfordshire 1985-6

Lyrics © samadhisound publishing

Download links: ‘Laughter and Forgetting’ (iTunes), ‘Fordor’ (iTunes)

Physical media: Gone to Earth (Amazon – cd) (burningshed – cd) (Amazon – vinyl re-issue) (burningshed – vinyl re-issue); Where Do We Go from Here? (Amazon)

All David Sylvian quotes are from interviews in 1986 unless indicated. Full sources and acknowledgments for this article can be found here. Originally published in August 2018 and subsequently revised and expanded in March 2021.

‘They were intended to be satirical lyrics, rather than romantic as they may appear at first. But as time’s gone on I’ve seen different levels of integration to it. “Laughter” is the lightness to be able to stand back and say, “This is all worthless”, and in that sense you can stand away and see more clearly what you’re trying to do, not just in music but in life. “Forgetting” is the ability to not dwell in the past on things you’ve done which are wrong, or things inside you which are wrong, it’s a kind of overcoming of yourself, of the fear of failure.’ David Sylvian, 1986

Once again you have nailed it. Thank you for your insightful piece

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks so much, Paula

LikeLike

Brilliantly put, I’m impressed at how you turn these thought provoking pieces around so effortlessly and so quickly! Can’t wait for the next instalment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks indeed, Kelvin

LikeLike

Very enjoyable read.

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This one song has been always a pivotal moment in my life as music listener.

At the beginning liberating me from guitar/drums canon I grew up with, and later always soothing my soul from harsher sounds I became accustomed to, thanks to gentle hugging by David’s voice.

You reminded me of all that …

your blog has been a lucky encounter

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing that, Gianfranco.

LikeLike

Wow – this song would not go away from my head so after listening to it repeatedly I googled it and came to this amazing writeup. Two things I wanted to point out: it is very succint. In the beginning the vocals are with bare minimum music – similar to A Fire in the Forest theme. The second part is when the music comes out and I really loved appreciating the flugelhorn through David Sylvian’ s work ( though Jon Hassell in early years – not sure why that stopped). Anyway thanks – looking forward to reading your other entries !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you found the site, Del. ‘Laughter and Forgetting’ is a wonderful piece of music indeed.

LikeLike

‘I started writing that song (‘Laughter and Forgetting’) as something tongue-in-cheek and pessimistic, but I ended up reacting to it positively. It’s right to be able to forget, and overcome certain obstacles. I tend to hold onto certain negative things in my past. It’s a struggle to put them behind me, accept them.’ David Sylvian, from Scared of Success: David Sylvian — The Man Who Would Be Invisible, Simon Witter, i-D, 1987

LikeLike