1982 started out with Japan on hiatus. Their Visions of China tour came to an end with a show at London’s Hammersmith Odeon on 27 December 1981, the dates having been overshadowed – at least off-stage – by tensions between band members, in particular between David Sylvian and Mick Karn. ‘Everyone has started on individual projects and Japan doesn’t exist for the next four or five months while we get on with other work,’ Sylvian told an interviewer the following March. ‘So most of what I do and what I think about revolves around what I’m going to do on my own…Steve [Jansen] and Mick [Karn] are doing session work at the moment. They’re performing with some Japanese artists who have come to England to record and Mick’s then going to do a solo single and I think Steve is too.’

As for the specifics of the lead-singer’s plans, ‘The first thing is to record a single with Yellow Magic Orchestra,’ the article recorded. ‘After that I’ve got a couple of ideas but I’m not sure which one I’m going to take up. Actually, I might make an album with our keyboard player Richard [Barbieri]. We might be doing an instrumental album together.’

The possibility of a joint project with Barbieri was mentioned in other interviews at the time. I’ve always thought this would have been an intriguing prospect, given how closely the two worked on the painstaking synth programming for Tin Drum, crafting a sound palette unlike any contemporary record I ever heard. The first project did come to fruition, however, albeit to be precise it was a double a-sided single with Ryuichi Sakamoto – one-third of YMO, alongside Haruomi Hosono and Yukihiro Takahashi.

The first experience of making music with Sakamoto had been for Japan’s 1980 album Gentlemen Take Polaroids on the track ‘Taking Islands in Africa’ (read the story here). Whilst released under the band’s name it was certainly the view of some band-members that this was more of a Sylvian/Sakamoto creation than one truly by Japan. From the pair’s first meeting for a magazine interview in the country of Sakamoto’s birth they hit it off. ‘I already knew some of his work at the time and immediately got on well with him,’ said Sylvian. ‘We wrote a song together, which went really well – very exciting.’ (1999)

After the ‘Taking Islands…’ experience there was a firm intention to work more together, it was just a matter of logistics with the two being extremely busy with schedules that being part of successful bands entail, and operating on different continents to boot. In fact both artists were considering what their next step might be away from the context of their respective band line-ups, exchanging ideas in a conversation for Japanese magazine Rock Show in February 1981.

Sakamoto was already established as an artist in his own right, his latest solo LP – B-2 Unit – having been recorded at the same time as Gentlemen Take Polaroids. It was a disc, Ryuichi told David, that ‘was almost like an experiment in self-indulgence. Now I know how far I can go, which has eliminated the need to do it any more, and from now on I would prefer to collaborate more with other musicians, and make music that is easier to communicate with.’

Sylvian agreed: ‘I find that more and more interesting, actually, working with other people. Working with you on this album […Polaroids] and for example working for the first time with someone like Simon House, who played violin. It was really nice to get outside people working, their reaction to what we were doing…it was a really nice thing that we’re going to expand on. We want to get different guitarists and different keyboard players, and maybe co-write songs with different people, just to add something totally new to the band, which might not otherwise happen.’

‘When we get around to doing something together,’ suggested Sakamoto, ‘I think it’d be interesting for you to work with Yukihiro [Takahashi, YMO’s drummer] too. I think you’d find you have a lot in common…I’d certainly be interested to hear, and work on, some of the things you want to do outside Japan.’

Sylvian: ‘There are lots of possibilities, lots of ideas I’ve got. I really would like to spend all my time in the studio. I really don’t like the touring. I mean, I love travelling, but the touring aspect of being in a band I find totally boring. I’d just like to walk from studio to studio.’

At this point in time future plans for both artists were expected to incorporate work inside and outside of a band context, each being a distinct setting. ‘There’s lots of things I’d like to do,’ Sylvian continued, ‘but I won’t waste a Japan album doing it. I’ll do it…as a solo project – which I haven’t been able to do up to now because of time and because companies haven’t been interested…There are different ways you can approach an album. I mean there are albums I want to do with just muzak, orchestrated muzak, maybe just a track a side, but as much as I want to do that I won’t do it with Japan.’

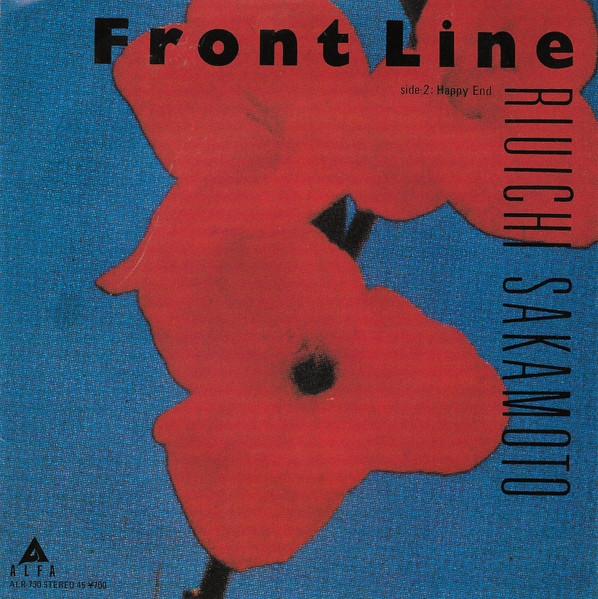

In April 1981, just a few weeks after the conversation with Sylvian, Sakamoto released a solo single called ‘Front Line’, backed with an alternative version of ‘Happy End’ which had appeared on YMO’s album BGM the previous month – the first of two new studio albums to be put out by the band that year, the other being Technodolic in November. It seems ‘Front Line’ could have been a collaboration with Sylvian, Sakamoto’s NHK-FM radio programme Sound Street is reported as the source for a comment that ‘David Sylvian liked the song and requested that he add lyrics to it and sing it, but this was never done.’

‘Front Line’ features bright synthesiser melodies with an overt Eastern grounding both in their sound and the musical scale employed as Sakamoto sings about ‘fighting a mind war/it’s called music/and I’m a soldier.‘ Ryuichi had told Sylvian about his approach to the music scene in his homeland at the time: ‘It’s very hard to listen to music here and take it seriously…When it comes to making a record, I sometimes feel that nobody is going to listen to it seriously anyway, so I try to keep the form as strikingly pop as possible, while also putting something of myself into it. I mean there’s so many records coming out all the time in Tokyo that it’s really quite something to get a decent listening among all of that, even YMO. I don’t mean commercially as much as in a purely musical sense. I mean, like there are all these young screaming girls who come chasing after you, which I don’t personally enjoy, but I think it’s important to make records which are going to appeal to all those people.’

The opportunity eventually came to collaborate when Sakamoto was in the UK to produce Akiko Yano’s album Ai Ga Nakucha Ne at London’s Air Studios, sessions in which both Steve Jansen and Mick Karn participated during the sabbatical from band duties. Once recording was complete in March 1982, the opportunity was taken for Sylvian, Sakamoto and Jansen to enter Genetic Studios in Berkshire, interrupted only by a performance on the Old Grey Whistle Test for which Japan reconvened with Ryuichi appearing as a special guest, timed to promote the release of ‘Ghosts’ as a single (see ‘Ghosts – live’).

Sylvian was asked at the time whether his current writing was along similar lines to Tin Drum, to which he responded, ‘Basically we’re using some of the musical ideas, yeah. We wouldn’t keep the actual theme going in the lyrics much longer though. We will do it for a while because there’s so many ideas I could take but I wouldn’t want to wear it thin. So maybe a couple more songs. After that I would try to forget it.’

Collaborating with Ryuichi lived up to long-held expectations. ‘We recorded the single ‘Bamboo Music’,’ remembered Sylvian. ‘That was an interesting step, because I hardly wrote with others anymore, not even with the other Japan members. And he had all that knowledge of music, thanks to his classical training. That fascinated me. From there our friendship has grown.’ (1999)

After Ryuichi’s sad passing in 2023, Sylvian looked back to the 1982 recording sessions for a Japanese publication celebrating Sakamoto’s life and music. ‘I think Ryuichi had a very limited period of time left over between a project he’d been conducting in London…and when he had to return home to Japan. I’d written a song titled ‘Bamboo Music’ but I didn’t play it for Ryuichi as I hoped we’d come up with something purely collaborative…

‘There wasn’t a discussion about direction…Ryuichi was primarily responsible for ‘Bamboo Music’, most of the compositional changes came from him as he played with the in-house Synclavier. It wasn’t the easiest track to respond to vocally but I managed to find one of some kind.’

‘Bamboo Music’ was the most commercial of the two tracks on the single and could certainly be said to pick up where Tin Drum left off. Complex rhythms are dominant as on the Japan album but something about the attack was different this time around. A variety of keyboard parts dip in and out, warbling undertones beneath principal lines that approximate the sound of real Asian instruments, from wind to metal chimes, in a style rooted in gamelan.

An interviewer in The Face observed, ‘If you don’t mind me saying so, I don’t think ‘Bamboo Music’ is much of a step forward. It sounds very much like Japan and I thought the whole point of branching out on your own was to satisfy creative urges that can’t be fulfilled within the confines of the group.’

‘It was the first time that I had worked with Ryuichi Sakamoto properly,’ Sylvian explained. ‘We both went into the studio and started writing there and then and the idea was to come up with something interesting. But there’s always a chance that it isn’t going to turn out exactly as you planned it. When I finished ‘Bamboo Music’ I couldn’t say that I was 100% pleased with it, but that was partly because of the circumstances, we were only together for about six days and it took me ages to finish the thing after Sakamoto left. As time goes by, I enjoy it more and more simply because the song has so many things about it that I would like to improve on. I always find that songs that I’m pleased with at the time of finishing – I never go back and listen to again – there’s no point, but with something that you’re not totally sure about you find that you get more attached to it as time goes by.

‘I’ve always written the stuff for Japan and normally I’ve directed it as well, so obviously something that I did is going to sound close to Japan even if it’s a solo project; I don’t think that’s a bad thing although I suppose it’s true that you should try to get away from what you were doing previously. However, that single was planned while Japan still existed, Sakamoto and I had wanted to work together for over a year. I’m in no hurry to break away and prove myself as a capable solo artist, I still relate to things I did with Japan, probably more strongly than any of the others do, because it’s all my material. I don’t actually differentiate between that single and Japan’s stuff.’

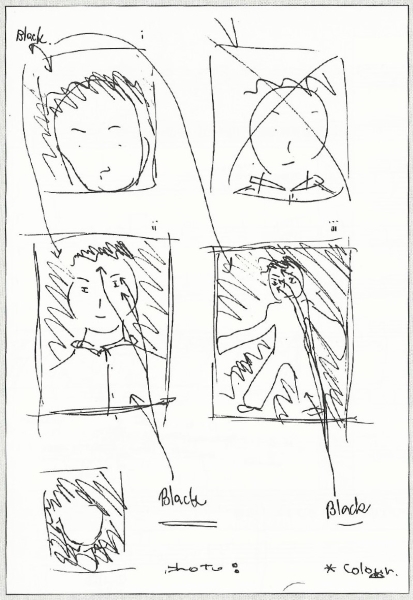

The single was accompanied by a promotional video shot in tight timescales to take advantage of another rare occasion when Sylvian, Sakamoto and Jansen were in the same place at the same time – at the end of Yukihiro Takahashi’s 1982 live shows for which Steve was in the band line-up. ‘The video was shot in Tokyo after [the] Yukihiro Takahashi tour,’ remembered Steve Jansen in an abbreviated posting on X. Production started at midnight and the video ‘went straight into editing by 7am – David Sylvian had to go to check in at [the] airport – I had to go to immigration to extend [my] visa which expired next day.’ Steve then ‘went back to editing with Pete Barakan.’ Once the work was finished it was rushed by car to David at the airport. (2023)

Ryuichi and David are seen playing Sequential Circuits Prophet keyboards, with Sylvian sporting a head-mic which no doubt seemed cutting-edge technology at the time. Jansen, on the other hand, intently ‘plays’ the typewriter, glasses perched half-way down his nose. ‘For that song I used the infamous Linn drum machine,’ said Steve, explaining why the rhythm sounds have a different feel to those on Tin Drum where the device was used only as an element within the drums. ‘But instead of programming it with the rhythm parts and syncing it to tape so that it played itself (as it was designed to do) I decided to play it in real time, which meant tapping buttons for each sound (drums, claps etc.) as the track played, which if you can imagine wasn’t too dissimilar to tapping a typewriter. In hindsight I’m not sure why I was even asked to appear in the video but since I was, I had to do something and perhaps it was the prospect of performing with a drum machine that prompted other, more visually interesting ideas (sweet jeezus the ’80′s) to be suggested.’ (2015)

The music is interspersed with archive footage such as labourers marching out to the fields to harvest the crop, large-scale processing in a factory setting, a bamboo forest (most likely the one in Kyoto to which Sylvian would return for the filming of Preparations for a Journey) and Buddhist monks. The device is similar to that used in the Oil on Canvas video of Japan’s final shows in London; it’s easy to forget that the ‘Bamboo Music’ video pre-dates that tour and the commemorative releases which followed.

Lyrically the song certainly continues the approach of Tin Drum, amalgamating images to create the impression of a scene without revealing too much about their author. A description of an experience and an observation of a way of life:

‘I walk through open fields

Where children sing

Bamboo music

A song of life itself

Played to win

In bamboo music’

The images of mass-production in the video imply a society where individuality is subsumed to the point of insignificance, but there is strength and purpose to be found in the inner life.

‘Building bamboo houses by the million

Lighting fires that only burn inside

Singing bamboo music by the million

Fighting for our lives’

Sylvian’s next lyric for a joint project with Sakamoto would appropriate the title of a Yukio Mishima novel – ‘Forbidden Colours’. The same is likely to be true here, this time referencing Mishima’s autobiographical work Sun and Steel, or at least borrowing the words to enhance the imagery.

‘A song of life itself

Of sun and steel

In bamboo music’

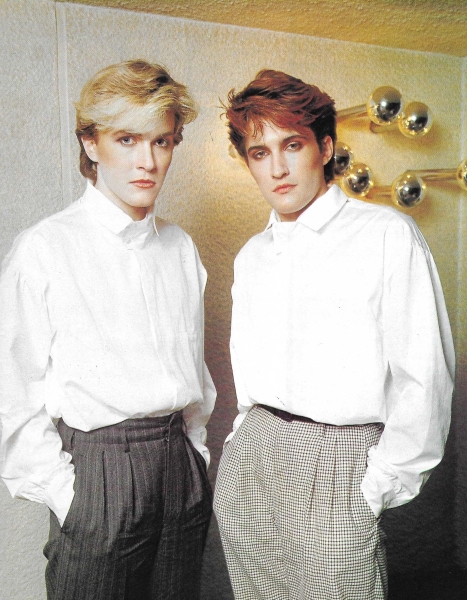

The featured photograph of Sylvian, Sakamoto and Jansen at the head of this article was taken at the time of the ‘Bamboo Music’ video production and included in the tour programme for Japan’s final, Sons of Pioneers, tour. The band were back together for one last time after their various side-projects for a final round of shows to say farewell to their fans. The set-list was made up of Japan numbers from ‘Life in Tokyo’ to Tin Drum, with no time allocated to the recent solo or collaborative work. It was stated at the time that ‘Bamboo Music’ was considered for inclusion along with Mick Karn’s solo single ‘Sensitive’ and something from Jansen/Barbieri, but whilst relationships were not at the all-time-low of the previous tour, agreement could not be reached between all parties and the band material was the common ground they shared.

‘Bamboo Music’ did, however, get a live rendition on the tour – just once. As the group moved on from Hong Kong for the final leg, the first Japanese show was staged at Tokyo’s Budokan on 8 December 1982. That night YMO members Yukihiro Takahashi and Ryuichi Sakamoto, together with Akiko Yano, guested at the end of the set, the entire performance broadcast on Tokyo FM. Bootlegs of the show have always existed and in recent years the recording has seen release through a legal loophole that seems to allow radio broadcasts to be made into cds or vinyl and sold through major retailers, no doubt with the musicians themselves seeing none of the financial benefit.

Akiko shared the lead vocal with David Sylvian for ‘Bamboo Music’, with her husband Sakamoto providing additional keyboards. Unfortunately Akiko’s microphone was insufficiently faded up at the start of the number, apparently the added complexity of having extra musicians on stage led to problems both with the performers being heard and being able to hear themselves, but it stands as the record of a special performance as the band wound down and a new phase started for all involved.

In 2011, Akiko Yano made her own recording of ‘Bamboo Music’, released as Yanokami, being a duo of Yano herself and Rei Harakami, an electronica artist who tragically died suddenly before the record – Tōku wa Chikai – was released. David Sylvian has expressed his fondness for Yano’s interpretation, even going as far as to say that he preferred her rendition to the original.

For my playlist, I like to precede ‘Bamboo Music’ with the version of ‘Happy End’ that was on the b-side of ‘Front Line’. It was included on cd in one of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s retrospective sets, Year Book 1980-1984. The track takes me back to those days of the early musical explorations between Sylvian and Sakamoto whilst they were still members of Japan and YMO respectively, and also spans the decades, given Ryuichi returned to the track’s inter-twining melodies for many of the solo piano performances that became a hallmark of his expression in later years.

‘Bamboo Music’

Steve Jansen – percussion, electronic percussion, keyboards; Ryuichi Sakamoto – keyboards, keyboard programming, MC4, marimba; David Sylvian –keyboards, keyboard programming, vocals

Composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto & David Sylvian. Lyrics by David Sylvian.

Produced by Steve Nye and David Sylvian, from ‘Bamboo Music’/’Bamboo Houses’, Virgin, 1983

Lyrics © samadhisound publishing

All artist quotes are from interviews conducted in 1981/82 unless otherwise indicated. Full sources and acknowledgements for this article can be found here.

Download links: ‘Bamboo Music’ (Apple)

Physical media: A Victim of Stars (Amazon) (burningshed); Year Book 1980-1984 (Amazon); Japan Live from the Budokan, Tokyo FM, 1982 (Amazon)

‘When we were in the studio, we both explored different directions, but there was always that common language.’ David Sylvian of Ryuichi Sakamoto, 1999

More about collaborations with Ryuichi Sakamoto:

Forbidden Colours

Forbidden Colours (version)

The Devil’s Own

Heartbeat (Tainai Kaiki II)

Zero Landmine

World Citizen – Chain Music

Concert for Japan

Dumb Type – 2022

Many thanks David, (Vistablogger)

LikeLiked by 1 person