In 1986 the oncoming age of downloads and streaming which would reduce the impact of album cover art to that of a mere thumbnail was way beyond comprehension. The cd was rising in popularity but was still a minority format, certainly beyond my student budget at the time. When David Sylvian’s Gone to Earth was released, LP sleeves were an art form in themselves, especially the glorious expanse of the gatefold. There was something so tangible and satisfying about holding and studying the record cover as the vinyl spun on your treasured hi-fi. For the duration of a side of music you were settled in one place, enjoying the full package that the artist presented.

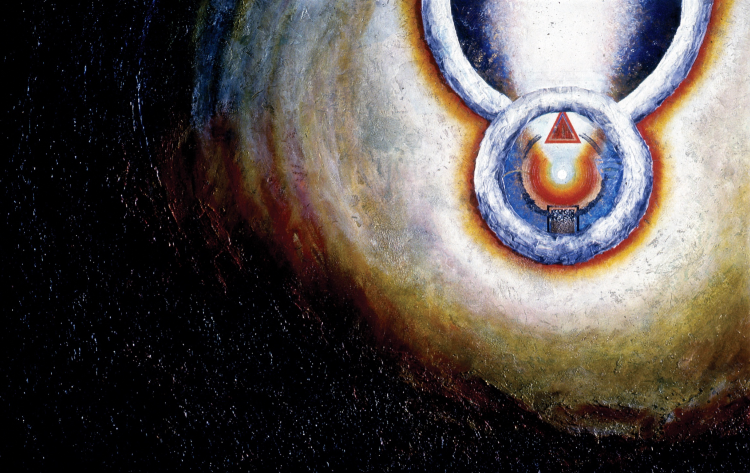

The golden autumn tones of the sleeve of David Sylvian’s second solo vocal album were striking. This time there was no trace of the singer’s own image, his presence subjugated in favour of an apparently higher purpose at hand. There was, of course, an earlier reference point with the same artist – Russell Mills – having produced the artwork for the Japan retrospective Exorcising Ghosts which followed closely on the heels of Sylvian’s debut, Brilliant Trees.

The press tour in support of Gone to Earth was extensive. On one of the European stopovers, Sylvian met a correspondent who was evidently enthused by the new offering. Before diving into an array of questions about individual songs, their philosophical basis, and the musical progression from Brilliant Trees, the first enquiry was: ‘If you can explain, is this cover telling something of the music? How much and what does the cover represent?’

‘Well,’ said Sylvian, conceding the significance both of the album’s title and its artistic presentation, ‘the original idea for the cover came from a diagram drawn by an English philosopher called Robert Fludd…He did these kind of geometric designs of heaven and earth, and that’s where the original design came from, the two circles. I showed this to the artist Russell Mills and said I wanted to base the cover on this picture.’

‘David and I had numerous meetings over a couple of months to discuss the cover art,’ Mills recalls, the wide-ranging conversations taking place at the artist’s residential studio of the time at Vauxhall in south-west London. ‘Fludd and others were considered as possible reference points. Many of my works, particularly in the early 1980s, were inspired to varying degrees by Fludd’s ideas and those of other alchemist philosophers.’ As the discussions homed in on particular possibilities, Sylvian brought along specific images for deliberation as to their relevance to inform the visuals for the album sleeve.

Sylvian was an admirer of Mills’ work, seeing a parallel in the textural and tonal qualities of his visual expression with an aspect of musical exploration. In a later conversation with Oliver Lowenstein for Fourth Door Review, he said, ‘I’d agree with you that Russ’ work was/is a visual analogue to the field of ambient music. That had to be a conscious influence or consideration in Russell’s development that saw him move away from the figurative and into these richly illustrative or suggestive images. That description doesn’t quite hold true for the Gone to Earth artwork which I felt pushed Russell in a slightly different direction at that time.

‘I came to his studio bearing books ripe with illustrations that I felt might work as an interesting starting point for the cover art or discussion thereof. Codex Rosae Crucis was one volume I remember bringing, and the graphics of Robert Fludd another. They had a clear influence on the nature of the finished work. Russ digested these elements, appropriated them, made them part of his own vocabulary.’ (2004)

Robert Fludd (1574-1637) was an English physician, mathematician and cosmologist with a passion for determining how the breadth of human knowledge could be assimilated in our understanding. His theories embraced Christian theology, the thoughts of Greek philosophers, and the esoteric beliefs of the alchemists and Rosicrucians. He is perhaps best remembered for capturing his thinking in graphic form, condensing the conceptual into more familiar imagery to promote understanding.

Fludd’s most famous diagrams encapsulate the relationship between ‘macrocosm’ and ‘microcosm’, showing how the physiology and spirituality of a human being has direct parallels with the nature of the cosmos and God’s role in its creation. His belief was that divine light invading darkness was responsible for the creation of the universe. The sun literally radiated the Spirit of God, and, as shown in the illustration below with the words ‘cor’ and ‘sol’, the heart was to the human being as the sun is to the universe, circulating the Spirit of God throughout the body.

The human’s head is closest to the divine light of God, with each of the larger concentric circles having both a light and dark hemisphere, the dark section being closest to the earthy mass that supports the universe. Fludd wrote that ‘The wonderful harmony of these two extremes is brought about by the Spiritus Mundi, the limpid spirit, represented here by a string. It extends from God to the Earth, and participates in both extremes. On it are marked the stages of the soul’s descent into the body and its re-ascent after death.’

The string may well be a musical reference, with Fludd elsewhere incorporating musical scales into his diagrams along with a representation of a monochord – a single-stringed instrument – and so bringing not only science and the heavens within the scope of his grand orderly vision, but also the arts.

‘I also wanted to include other forms of symbolism,’ said Sylvian, ‘…the symbols on the cover – like the triangles – this is fire, water, earth and air. And really, I suppose that ties in in a way with a lot of the lyrics on the album. The lyrics have a double-meaning in many cases. There are references to the elements on the album, continuous references, and they have both the references to the physical world and to in a higher sense, a spiritual sense. So… it ties in.’

Surrounding the central circle that is the focus of Mills’ composition for Gone to Earth there is a red triangle at the top, presumably the refining Fire that is the closest element to heaven, the three points of the triangle representing the trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. As we move clockwise to the right there is an upturned triangle with its blue waves depicting Water, and we can surmise that the dark square at the bottom represents Earth and the barely visible arc to the left is Air. Triangles were very much part of Fludd’s symbolism, and the four base elements regularly appear in his depictions of order in the natural and supernatural realms. However, the representations in the final artwork for Sylvian’s album also draw on wider reference points.

‘You’ve identified all the symbolism correctly, although not all of the elements relate to Fludd,’ Russell Mills confirmed to me. ‘I researched a lot into Fludd and Galileo and the early alchemist philosophers when approaching the painting for the cover. I did hear the tracks for the album before proceeding with the commission, and David and I talked a lot about their ideas and decided that they did reflect much of the music on the album.’

I know some fans had the opportunity to visit the offices of Opium Arts in central London and saw the original painting hanging there. However, it is only in the last few years that I have seen photographs of Russell’s canvas and what is immediately striking is the sheer scale of it.

Seeing the picture in its full extent, the darkness of the bottom left corner is offset by the radiance in the upper right, the warmth of the colours there emphasising the concept of a heavenly light of hope in the vastness of the cosmos. Even in this abstract setting the colours bring to mind the skies of J.M.W. Turner, whose work Mills has acknowledged as an inspiration more generally. Another notable aspect is how thickly applied the paint is, especially in the darkness of the abyss, resulting in a highly textured surface that resembles the tactile, gestural brushwork of Anselm Kiefer.

As Russell indicated, there was a direct link between the concepts behind the cover-art, the resulting image and the music itself. ‘The title of the album, Gone to Earth,’ Sylvian told his enthusiastic interlocutor on the press tour, ‘is in a way to do with the idea of the spirit existing before birth and existing after birth. And the idea of the spirit coming down and taking physical form, in that sense “gone to earth”.’

Evidently Sylvian was investigating various belief systems to discover his own guiding light and his expression in music was part and parcel of the process. ‘Basically I see creation as an act of faith,’ he stated. ‘The whole process of recording and writing this material is an act of faith for me. In the past, all great works were based on faith and it’s only in the recent past that faith has become a dirty word, and that should be changed.

‘Through the work it’s possible to show an appreciation of nature and a love for life and its value. Yes, it has to do with finding the true value of life within yourself and not looking for substitutes outside. My reading is more factual than literary, just reading up on subjects which help me throw light on my experiences. It covers various forms of religion and religious belief from Buddhism, Christianity to The Kabbala and some forms of magic to Rosicrucianism – just an assortment of sources that help me pinpoint the true values of life. It’s a learning process, no matter how fast you read in practice it doesn’t change you. You have to change from experience and not from intellectual reasoning.’ (1987)

The rejection of faith in modern society, often a violent rejection, was at the core of the lyric. Perhaps this was even meted out by an organised religion unwilling to tolerate alternative belief systems. ‘‘Gone To Earth’ is…about the fact that most of the things that I see of value in the world are trodden down, the value is not seen, aggression is always used against it,’ explained Sylvian. The opening scene takes up the symbols of a religious ceremony…

‘With a burning candle

A book of holy things’

…a physical rebuttal ensues…

‘They’ll throw you up against the wall

Bind your hands with string’

Ancient spiritual wisdom and truth gives rise to irrational fear…

‘Caught in this sudden shower

Our host of heavenly kings

They’re all victims of circumstance

Of ancient bells that bring

All the fear in the world, naked and shy

Down upon our heads with no reason why’

For all the noise and the violence, nothing can deny the truth of the spirit taking on flesh for a life on earth.

‘And though voices may holler

For all they’re worth

The rabbits have fled their burrows

Gone to earth’

‘I did see the record as being a reflection of that alchemical process from base instincts to the development of higher properties or attributes,’ Sylvian later explained. ‘I was reading Gurdjieff around this time but was intrigued by the Gnostics, the Rosicrucians also, Pascal etc.’ (2004)

Only two performers feature on the title track, guitarist Robert Fripp and Sylvian himself. In Fripp, Sylvian found a kindred spirit in these explorations. In the mid ’70s, Robert had experienced a personal epiphany, an absolute conviction that led him to leave music behind for a time and to follow a very different path. ‘All the contradictions of being a rock musician… it was simply not giving me the answers I needed,’ explained Fripp in an ’80s TV interview. ‘I had been looking around for help, direction, and one Sunday night in my bed in Putney I read the Second Inaugural address of J.G. Bennett to the second basic course at Sherborne House, and the top of my head blew off, because I knew this was exactly what I had to do.’ He would move into Bennett’s school – or International Academy for Continuous Education, as it was named – at Sherborne House for the residential course that ran from October 1975 to August 1976. Bennett himself had by this time passed away, the course being run by past students and by the philosopher’s son, Ben.

‘It’s not rational. Part of me recognised something which the rest of me had to go along with,’ Fripp attempted to explain. ‘It’s so difficult to talk about these things… I saw what it was to be a human being… I saw what real freedom for a human being is, and I saw that it was possible for me to have that, but I also saw the price I had to pay. And at this time King Crimson was just about poised to be the most successful rock band in Europe… So how can I throw away my career to go and live in a house with a hundred loonies at Sherborne in very difficult conditions and, if you like, give up everything I’d acquired up until the age of twenty-eight? At the same time, I knew I had to do that.’

Bennett’s teachings were rooted in and developed from what he had himself learned from George Gurdjieff, not least from his time spent at the latter’s own school in France. When Sylvian and Fripp met to record for Sylvian’s follow up to Brilliant Trees, this was an obvious topic for conversation. ‘My interest in all things Gurdjieff led me to the writings of J.G. Bennett,’ explained Sylvian. ‘Of course, on meeting Robert for the first time I spent far more time inquiring of Mr and Mrs Bennett and their teachings than recording. Actually Robert set up a number of Frippertronics loops so we put the machines into record and left them to it, allowing us to take tea and talk whilst simultaneously working.’ (2004)

Interestingly, Bennett drew parallels between Fludd’s visualisations, the symbolism of Rosicrucianism and Gurdjieff’s ‘Diagram of Everything Living’, so the various threads of influence draw together. And of course, J.G. Bennett’s voice is heard on ‘Gone to Earth’ in what is akin to a verbalisation of Fludd’s representations of the journey of life:

‘the soul goes beyond being and enters this divine world’

The precise source of the quotation is unknown to me, some have said it is taken from a talk concerning Bennett’s autobiographical volume, Witness; if so, it’s not a direct quotation from the book. It is quite possible that Fripp was the provider of the listening material that led to its inclusion. Whilst Robert returned to the music world following his time at Sherborne – famously prompted by the invitation to record with David Bowie and Brian Eno for Heroes – his fascination ran deep and he remained closely connected with the Bennett family. Indeed, the J.G. Bennett foundation website tells us that, ‘At Sherborne House, between October 1971 and December 1974, more than 450 cassette recordings were made of talks by Mr. Bennett to public audiences, various groups of students and other groups of people. Most of these recordings were preserved, although some original recordings were sent out to group leaders overseas, and have since been lost. When The International Academy for Continuous Education closed its doors for the last time in August 1976, Elizabeth Bennett entrusted all the remaining recordings, as well as some 120 recordings made prior to the Sherborne experiment, to the care of Robert Fripp… Robert undertook the task of editing, mastering and publishing some of the major recordings…’

Bennett’s voice was present on Fripp’s 1979 solo album Exposure. The title track takes his phrase ‘it is impossible to achieve the aim without suffering’ as a recurring motif, chiming with Robert’s reflection above on the cost associated with human freedom. The words are from the First Inaugural Address to the International Academy for Continuous Education, Sherborne House, which itself appears as a track on Exposure, albeit condensed into a few seconds of what sounds like static by deploying a process it was claimed extraterrestrial intelligences might use to send information across the universe. On ‘Water Music I’, Bennett’s taped voice can be heard above Frippertronics, warning of a coming ice age and rising sea levels that would flood major cities in the world, before Fripp, Brian Eno and Peter Gabriel combine for the exquisite ‘Here Comes the Flood’.

Plenty of precedent then for Bennett’s voice being interwoven into ‘Gone to Earth’. ‘I’d met Robert a few months earlier when we recorded ‘Wave’ and he mentioned Gurdjieff and J.G. Bennett to me. I had been using tapes of people speaking in various ways before, so when I found some tapes of J.G. Bennett I decided to use them on the record. I mean I’m not afraid of allowing somebody else to have a large input into the music. I think you’d only be afraid of that if you’re a little insecure about having your personality come through a piece of music, and that in itself is not the ultimate thing.’ (1987)

‘The context the sample was used in, it was like this moment of clarity in an otherwise chaotic universe. So it was to indicate, to some degree, the possibility of divine insight, if you like. I think on any path of spiritual development you have these moments of revelation, of liberation, you know, you suddenly stand on some fresh ground. There is a clarity to those moments which are really intense. They don’t always last for that long. You can be immediately plunged into a whole new process. A whole new cycle and you have to get on with that. But those moments of clarity, those mini epiphanies, are so strong that they drive you on, regardless.’ (1999)

Fripp’s muscular solo brought the violent conflict of the scene conjured in Sylvian’s lyric to life. ‘That track is the nearest I’ve got to what I’ve been aiming at all this time,’ said Sylvian on release, ‘just because it’s so raw. It was almost recorded live, with no overdubs.’

‘That was written a long time before I went into the studio and what I intended to do was a version with Robert and a version with Bill [Nelson]. I unfortunately ran out of time with Bill, so I only had time to do the version with Robert. I just sat down with a guitar, sang the song to him and said, “What would you do?” He responded by saying, “Ah! I would do something like this”, and that’s how it all started. He recorded the guitar parts all in the first take and the whole thing was spontaneous. I liked his aggressive approach, it was something that I wanted to do. The way that Robert reacted to the song was totally in keeping with what I wanted.’

Sylvian ‘recorded the rhythm track there and then…The vocal went down soon after, and in all, it was a very spontaneously created song with the minimum of studio overdubbing.’ (1990)

The track stood apart from ‘Before the Bullfight’ which preceded it and ‘Wave’ that followed for its hostility, a joust between guitar and vocal reminiscent of Fripp’s duel with David Bowie on ‘It’s No Game (No. 1)’ from Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps). ‘Well it’s a very small part of my character and so it tends to be a very small part of the music,’ explained Sylvian of the aggression. ‘Maybe on Brilliant Trees it would be ‘Pulling Punches’, on this one it would be ‘Gone To Earth’, but because it doesn’t constitute a large part of my character, I don’t think I could produce an album’s worth of music, it would mean a fundamental change in my character.’

For Fripp, there was something new in his contribution to this album that challenged the very fundamentals of his technical approach to the guitar. It was the first session for which he used the New Standard Tuning that would be the cornerstone of his craft for decades to come. He had attempted to use it for an invitation just prior, but it proved to be too early in his mastery of the new convention. ‘It was in 1985, right at the beginning, in the spring. I’d only been working with the tuning for a month or two, and I was asked to play on a Scott Walker album that Eno was producing [the album was not completed]. I went to Phil Manzanera’s studio to do this, and I was given these written chords, very complex chords. It was too soon for me to be able to figure out these chords with this tuning on their time. So for that one I had to acknowledge I couldn’t play that in the new tuning, and I went back to the old one.

‘However, not long afterwards, David Sylvian called me for Gone To Earth. I was a little more familiar with it, but I had no parts to read as such, no really dense extended chords that would make the eyes boggle, let alone the hands. So, nevertheless, I opted to brave it out, and there’s nothing like exposure to public ridicule to galvanise the attention. So I’m afraid David had to duck a little in the studio as one or two bold notes flew by. But that was really the no-turning-back point.’ This recollection was made in 1991, by which time Fripp was still observing: ‘I’m not what I would understand as fluent in the tuning—I’m still learning the tuning.’

For the 2019 vinyl re-release of Gone to Earth and the other early solo discs, a beautiful series of photographs by Yuka Fujii was used for the cover art of the new presentations. It was a delight to have these new sleeves which were evidently put together with a great deal of care and showcased many unseen images. The vinyl revival also took me back to those 1980s days of luxuriating in the music with visuals in large scale, the attention fixed for a period. I will, however, always have an over-riding affection for the original sleeve with its artistic representation of the ideas with which Sylvian was enamoured at the time. For the re-release, Sylvian is pictured sat in the driver’s seat of a classic Volvo p1800, a shot dating from the specific time of the album’s creation/first release. For me, Russell Mills’ original cover is as timeless as the music captured on the two discs of vinyl protected by the gatefold.

In time, Sylvian would move on from the concepts of Fludd et al. ‘I was briefly held captive by the symbolism, the language, the romance,’ he admitted, but ‘ultimately I felt this knowledge obscured as much as it revealed.

‘The straight ahead clarity of the Buddhists, the lack of obfuscation, the indisputable benefits and results of the practice determined that I should stick with the [Buddhist] teachings when other avenues of interest had lost their charm.’ (2004)

‘Gone to Earth’

Robert Fripp – guitars, frippertronics; David Sylvian – vocals, guitar

Music by David Sylvian & Robert Fripp. Lyrics by David Sylvian.

Produced by David Sylvian and Steve Nye, from Gone to Earth, Virgin, 1986

Lyrics © samadhisound publishing

The voice of J.G. Bennett by kind permission of Mrs E. Bennett

Recorded in London and Oxfordshire 1985-6

All David Sylvian quotes are from interviews in 1986/87 unless otherwise indicated. Quotes from Russell Mills are from 2023. Full sources and acknowledgments for this article can be found here.

The featured image is of Russell Mills’ painting for the cover of Gone to Earth. Russell has high quality art prints of this image available in a limited edition here, with Exorcising Ghosts and Trophies also available. His website can be viewed here.

Thank you for Sven Jacobs for permission to share the image of the original painting from his private collection.

Download links: ‘Gone to Earth’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Gone to Earth (burningshed – cd) (Amazon – cd) (Amazon – vinyl re-issue)

‘Robert’s played some of his best work on other people’s material. He knows that too. He loves to just walk into a session and feed back off of the energy in that session. This is a good example of that. I felt that Robert and I definitely connected on Gone To Earth.’ David Sylvian, 2003

A fascinating chronicle! I would have loved to toss around philosophical ideas on the “Universe, how and why man is here and the struggles we all experience before we move into the next dimension and the mysteries in that element. Fludd, Robert and David would be a trip to sit down with and trade philosophies. I believe they would find my ideas rather intriguing, more in line with their beliefs but deeper. Now I see why David’s music has captured my soul. fyi, I am nearly 80 in body and 30 in soul!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Paula, for reading and for sharing that.

LikeLike

A brilliant article! I had never seen a photograph of the original art before! Remarkable. Would love to see it in person.

As you post another great piece, I would love it if you were able to publish all of your articles in a physical form as they really deserve that honour.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the kind words and encouragement, Jon. The original painting really is quite something, isn’t it?

No plans for anything other than online publication at this time, but thanks for sharing your enthusiasm for preserving them in a physical format.

LikeLike

Thank you. I enjoyed reading this article, which sheds some light on the origins of Russell’s artwork ‘Gone to Earth’.

I was privileged to experience the sheer scale and texture of this canvas and David’s album with Roberts input remains one of my favourite LPs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Amanda. Good to know that you got to see the original artwork. I think the texture comes over quite well in photographs and on the cover, but no doubt nothing can compare to seeing it with your own eyes

LikeLike

I wish David’s work with Bill Nelson had been discussed. Bill’s solo work at the exact same time reflected a great amount of contemplation in the same spiritual questings as David, and it would have been very enlightening to see exactly what parallels and what diversions existed between them, and how these perspectives fed into their collaborations on the “Gone To Earth” recordings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the comment. I agree that the series on the ‘Gone to Earth’ album won’t be complete without some reference to Bill Nelson’s spiritual quest and parallels with David’s own thinking at the time. I shall certainly aim to explore that before the articles are complete. There is some reference to Bill’s excellent guitar playing in the previously published instalments on ‘Before the Bullfight’, ‘Sunlight Seen Through Towering Trees’ and ‘The Healing Place’ – links in the ‘More about Gone to Earth’ section at the end of the article. Thank you for reading and for sharing the observation.

LikeLike