March 2009. The venue is on the north-east coast of Gran Canaria, the near-circular island surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean. Part of a Spanish archipelago but geographically much closer to Africa. In fact, at its closest point, Morocco is less than a hundred miles to the East. Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno (CAAM, or the Atlantic Centre of Modern Art) in Las Palmas has dedicated exhibition space to the second architecture and art biennial of the Canary Islands, with parallel presentations taking place at a number of venues across Gran Canaria.

Silencio, silence, was the chosen theme of a festival that was conceived on this occasion as a meditation on the landscape of the Canary Islands and their unique geographical, topographical and sociological make-up. The event brochure sets the scene: ‘Through photographs, paintings, projections, installations and architectural and landscape projects we seek to reveal a number of different approaches that arise from analysing landscape as an object and as a process: a task which combines elements from architecture, geography and art… these provide us with a framework to analyse and reflect on the elements that form the mosaic of relationships which articulates and constitutes our environment, taking the production of the landscape and its progressive modification over time as our point of reference.’

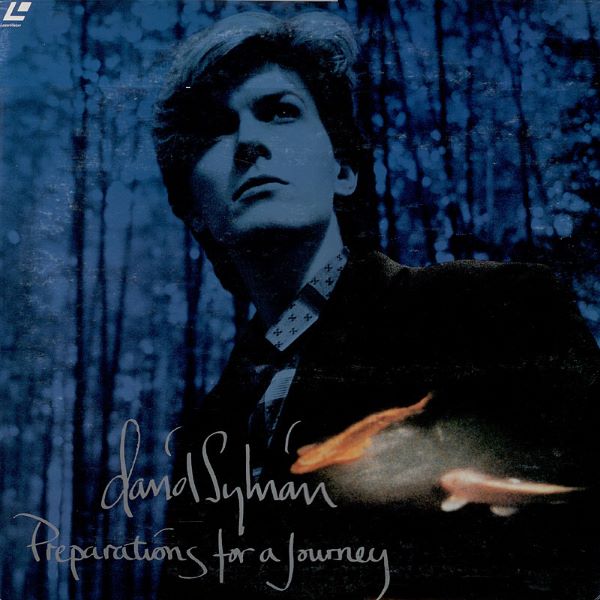

In the middle of the balcony galleries is a square room with central seating and a sound system of five speakers surrounding the visitors. Little publicised outside of the festival, this is David Sylvian’s sound-installation in response to the local landscape: Cuando Volvamus, No Nos Conocerás, or in translation, When We Return You Won’t Recognise Us.

‘A work of this nature starts with a visit to the location to absorb something of the spirit of the place, the landscape and its inhabitants,’ wrote Sylvian in the guide to the 2nd Bienal de Canarias. ‘If I’m fortunate, an intuitive connection is made from which the work will evolve. It’s from this point that a path of inquiry is suggested and pursued.’ There are clear parallels with his earlier site-specific sound installation When Loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima, commissioned on the occasion of Sylvian’s visit to that tiny island in the Seto Inland Sea and premiered in 2006.

‘Two images stayed foremost in my mind following my first visit to Gran Canaria. One, of a hunting dog, which I photographed as it prowled nervously, cautiously, seemingly wild, around a car park high in the mountains above Las Palmas. The other; the way the sunlight played from sunrise to sunset, on what was at one time considered, by the aborigines of the island, to be the holy mountain of Ajódar, and which is now commonly referred to as Gáldar mountain.’ The hunting dog will be familiar to followers of Sylvian’s photography and featured in a Chris Bigg-designed creative for the installation, as shown at the head of this article.

‘With these images came impressions of a powerful sense of place, of what it means to belong to the land, to feel rooted in it, to appropriate it or, alternately, to be exiled, displaced. There are many peoples of the world who believe they’ll be reborn in their homeland when their current lives end. In such instances the marriage of self to place takes on broader ramifications, metaphysical dimensions. I wondered if I’d find something in my research of the island’s early inhabitants that might echo a philosophy of this kind.’

Sylvian set out to explore the story of the first inhabitants of the Canaries, those present long before the Europeans arrived and reputedly living on the islands in the first millennium BC. ‘When I started my research on the Guanches I was disappointed to find that there was relatively little information to go on. With the exception of a few outstanding characteristics, their footprints appeared all but erased with the passage of time.’

However, inspiration struck from an unusual source: an academic article published in the European Journal of Human Genetics in 2004. ‘One detail I came across did strike me as fascinating. Despite the continuous changes suffered by the population, aboriginal mtDNA [direct maternal] lineages constitute 42 – 73% of the Canarian gene pool. The intersection I’d been hoping to find where seemingly independent lines of inquiry might cross appeared to me in the connection between the physical or scientific reality of the biological make up, the links to lineage (genetic genealogy), location and, to move beyond the realm of science into intuitive logic, the interior life of a community or people. An implied cultural heritage, a plausible continuum where, on first glance, there appeared to be none.’

Sylvian’s experience of the place and discoveries about its people provided the spark for his musical contribution to the festival’s theme. ‘From here I developed working guidelines for a predominantly improvised piece of music. There were compositional elements involved but they allowed for a significant degree of indeterminacy. I supplied references for the musicians of both a musical and non-musical nature. How they interpreted these and brought the information into play (or otherwise) on the day was unique to each performer. We recorded four takes of the improvisation, each based on the same identical guidelines. We ended up with three markedly different pieces that varied in colour, density and dynamics. As the day wore on the improvisations became more refined and it was from these that I selected the final work. The recording was edited and then mixed in 5.1 surround.’

Clockwise from top left: messenger; untitled; location; location, location.

Saxophone player John Butcher was among the musicians invited to Air Studios to take part. This was his first experience of recording with David Sylvian, joining an experienced group of improvisers gathered for the project. Alongside him were trumpeter Arve Henriksen who had previously appeared on the Nine Horses album and Naoshima installation piece, Manafon contributor Toshimaru Nakamura with his no-input mixing board, and two fellow debutants to a Sylvian session: percussionist and AMM co-founder Eddie Prévost, and Günter Müller whose electronics set-up processes sounds generated from ipods.

At one stage in the production of the Manafon album, Sylvian had considered incorporating strings into the musical landscape, with Dai Fujikura’s arrangement for ‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence’ an experiment in the approach. The concept would form the catalyst for the re-imagining of some Manafon tracks on the subsequent disc, Died in the Wool. For the sessions towards the commission from the Bienal de Canarias, Sylvian decided to bring a string ensemble into the studio to record alongside the electro-acoustic improvisers. The composer Dai Fujikura was present to direct the Elysian Quartet who were supplemented by both an additional violin and viola player.

‘The process of creating the piece was informed by the Manafon sessions themselves,’ said Sylvian, ‘but went a step further by having a written text regarding the context of the installation and the concept behind it with specific references to sound, and by having Dai “improvise” with a sextet of string players. This was handled by settling on a handful of chord clusters prior to the session. Dai formulated a series of hand gestures that would indicate which combination of responses was required from the sextet at any given moment in time. I believe we recorded five takes total and each take was vastly different from the one prior. I did speak with the ensemble after each successive take to guide them towards, not a specific result—that would be impossible and would defeat the purpose of working in this manner—but a narrower, sonically and dynamically more-defined, field of inquiry.’

John Butcher told me how everything came together at Air Studios on 19 January 2009 and through the exchanges leading up to that day. ‘The guidelines for the improvisers came mostly in an email where David Sylvian expanded on the concept before the session. It included the photograph he’d taken of a stray dog in a misty car park on Gran Canaria. Apparently the island name is connected to “Island of Dogs”.

‘He sent a couple of articles about the early inhabitants of the islands and the genetics research you mention. There was also discussion about the whistling language of the island.’ The musicians were given access to a film about this unique system of communication used on the island of La Gomera in the Canaries, a practice developed to enable the transmission of messages within the physical constraints of the landscape to which they were born. The Silbo Gomero, as it is known, was in the process of being recognised by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) given its importance to the ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’ and the need to preserve the ancient practice into the future.

Like the genetic links that Sylvian had discovered, here was a clear association between today’s islanders and the communities that preceded them over hundreds of years. ‘The whistled language of La Gomera Island in the Canaries, the Silbo Gomero, replicates the islanders’ habitual language (Castilian Spanish) with whistling,’ explains the UNESCO citation. ‘Handed down over centuries from master to pupil, it is the only whistled language in the world that is fully developed and practised by a large community (more than 22,000 inhabitants). The whistled language replaces each vowel or consonant with a whistling sound: two distinct whistles replace the five Spanish vowels, and there are four whistles for consonants. The whistles can be distinguished according to pitch and whether they are interrupted or continuous. With practice, whistlers can convey any message…Taught in schools since 1999, the Silbo Gomero is understood by almost all islanders and practised by the vast majority, particularly the elderly and the young. It is also used during festivities and ceremonies, including religious occasions. To prevent it from disappearing like the other whistled languages of the Canary Islands, it is important to do more for its transmission and promote the Silbo Gomero as intangible cultural heritage cherished by the inhabitants of La Gomera and the Canary Islands as a whole.’

For John Butcher, these scene-setting materials were helpful to preparation and enabled participants to arrive attuned to the territory that Sylvian wished to explore. ‘Overall, the information set a mood and a mental landscape for the piece. I’ve found that with experienced improvisers small elements of direction can have quite profound effects on the musical outcome,’ he says.

‘It was the first time I’d met the string players, Dai Fujikura and Arve Henriksen. I’ve played with Eddie and Toshi for some years and twice previously with Günter.

‘For the main part of the session we played all together. The five improvisers were separated from each other, and the string players, by baffles – and we used headphones to hear each other. Mine kept cutting out – and despite two changes of headphone amp the problem remained. So, for me it was initially tricky… and it led to a discussion about the importance of hearing each other properly. Obviously that’s always needed, but when you don’t have a pre-arranged part it’s completely vital.

‘Improvisers really need to feel they’re all in the same acoustic space, and headphones don’t help this. So we decided to remove the baffles (or maybe just some of them) and forgo the clean recorded separation for the intimacy of playing together more naturally. I think the music improved after this.

‘So we probably did a couple of takes (the full group) with baffles and couple without.’

Ros Stephen was part of the string ensemble and explained to me how their improvisation worked, triggered by signals from Fujikura. ‘Dai had hand symbols for the kind of sound he wanted us to make, for example a T-shape meant play over the tailpiece. There were several others – I can’t remember what they were – but we used various extended techniques such as moving the bow in a circular motion over the fingerboard, playing on the tailpiece, playing on the bridge. My overriding memory is how incredibly quietly we had to play. The takes were around forty-five minutes each – we had to be completely still, breathing as quietly as possible and playing super quietly, so it required a lot of concentration.’

Sylvian recalled the progress over the successive takes. ‘Everything fell into place for me on the fourth. There was a fair amount of editing in the mixing stages but nothing that detracted from the form the original improvisation had taken.’

John Butcher: ‘Interesting that it was the later recordings he used. I’d say Sylvian’s been quite selective and chosen part of the recordings to re-compose the music for the final piece. He’s obviously got a very good ear for imagining possibilities.

‘There wasn’t that much verbal direction during the actual session – except I do remember Sylvian gently encouraging us towards playing more sparsely and quietly. In some ways one picks up intuitively on the “feeling” of what is being aimed at in these kind of situations. And as some of the players had worked with him before, I could try to sense things from how they were approaching the music.

‘I think of the improvisers I like as being composers, in the sense that they use improvisation to create their own music. So it’s not simple for someone “outside” to direct this and still keep the qualities that make the players interesting in the first place. Pinning things down can kill them. Sylvian seems very good at keeping the freshness of the improvised ingredients whilst moulding them to his intentions.

‘I first heard him on Blemish, and particularly liked the tracks with Derek Bailey where such different worlds were brought together in a way that really worked but without diluting either person’s voice.’

When Died in the Wool was released in 2011, Sylvian elected to include ‘When We Return You Won’t Recognise Us’ as a second disc in the set. ‘All said and done it seemed to belong to this body of work,’ he concluded. The principal challenge was converting what was an immersive surround-sound installation to a stereo cd format. ‘I was moving from the spaciousness of a 5.1 surround mix, which was how the audio was set up for the installation, to a stereo one. The composition should hold up either way so it was a matter of maintaining that sense of spaciousness regardless of limitations. I’ve been working in the realm of stereo all my life so this wasn’t a difficult transition to make, but whilst I was handling these adjustments I took the opportunity to edit the piece further, to improve on it by bringing in other elements from earlier takes, mainly very subtle additions which spoke to the natural dynamics of the piece and the intricate details of sound design.’

Immediately following the recording session for ‘When We Return…’, John Butcher was interviewed in an adjoining room at Air for the samadhisound film Amplified Gesture which was first included within the Manafon deluxe edition. The film explores the philosophies and practice of a cast of improvising musicians. Having just played with a new constellation of artists, he describes the drive that keeps him creating. ‘I think the perpetual stimulus is a very mysterious thing. It’s how renewable it is through the process of playing with other people. How any two circumstances are never the same. How there are new players always coming up with an interest in this way of working, who may have very little difference from some of the previous players but enough difference – because they are different people – to have a different slant on it. And somehow you play with them and you are led different ways; something new comes…It’s got to be the playing with other people that is the drive to continue. The surprise is what they can make you do.’

It’s something that holds true whether in live performance or during a recording project such as that with Sylvian. ‘When one improvises in a room to an audience there’s a sense of a beginning, middle and end that you’re all sharing – even if the music is very non-narrative.

‘When you know that the material is likely to be extracted and re-composed, as in this session, it’s important to still try to play in-the-moment and to feel that everything counts. Otherwise you lose the subtlety of the interactions, and the magic of how all the individual decisions add up to something no single person is in control of. The day in the studio was very conducive to working inventively in a (mostly) ego-less way.

‘Listening again to ‘When We Return…’ I feel that David Sylvian has been very creative in shaping the raw material into something that seems to grow and develop naturally even though it’s not verbatim. The piece doesn’t sound like collage – it flows very organically and at the same time you sense a guiding hand. Its surface is quite gentle but it contains sharp edges and dark corners. It hovers between ease and unease.’

John Butcher and Toshimaru Nakamura took the opportunity to record a disc of their own the day following the Air sessions, further exploring a musical relationship that had started with a performance several years earlier in Tokyo. In some ways it’s an unlikely partnership. John explains the fascination for him: ‘The saxophone is a very physical instrument. The sound is completely dependent on breath and it all comes from having a piece of vibrating cane inside your mouth that you try to control with your lips, tongue and throat. Toshi’s instrument is close to the opposite, it has almost no need for his body – he can manipulate the most incredible sounds by the tiniest twist of a knob. I’m interested in what happens when you bring these poles together.

‘At the Dusted Machinery session we improvised a number of pieces and chose the parts we liked for the album. To take a step closer to Toshi, I also worked with some saxophone-controlled feedback – which doesn’t use the reed/breath – just the saxophone body and amplification.’

My favourite track from the collection is ‘Maku’ where there is a symbiotic interaction between the pulsing frequency of the sounds that Nakamura coaxes from his no-input mixing board and those created by the reed vibrations of Butcher’s woodwind.

‘When We Return You Won’t Recognise Us’

John Butcher – saxophone; Arve Henriksen – trumpet; Günter Müller – ipods; Toshimaru Nakamura – no-input mixing board; Eddie Prévost – percussion

Elysian Quartet under direction from Dai Fujikura: Emma Smith – violin; Jennymay Logan – violin; Vincent Sipprell – viola; Laura Moody – cello; with Ros Stephen – violin; Charlie Cross – viola

Music by John Butcher, Dai Fujikura, Arve Henriksen, Günter Müller, Toshimaru Nakamura, Eddie Prévost and David Sylvian

Produced by David Sylvian. From Died in the Wool, Samadhisound, 2011.

Mixed by David Sylvian. Recorded at Air Studios, London by Rupert Coulson.

Commissioned by the second architecture, art and landscape Biennal of Canaries 2008-2009

Grateful thanks to John Butcher and Ros Stephen for sharing their recollections of the creation of this piece for the article. All David Sylvian quotes are from 2009 when the installation was staged or 2011 when the recording was released, unless otherwise indicated. Full sources and acknowledgments can be found here.

The article from the European Journal of Human Genetics can be found here.

Eagle-eyed readers may note that a recording date of March 2009 is stated on the cd release of Dusted Machinery, but John Butcher confirms that the recording was in January as noted in this article.

Download links: ‘When We Return You Won’t Recognise Us’ (iTunes); ‘Maku’ (bandcamp)

Physical media links: Died in the Wool (Amazon)

‘Usually my interest in group improvisation is where you have a situation where you all feel like any one of you could change the direction of the music at any moment by a very subtle change of your own direction. You don’t have to hammer it to have a change…small changes can lead to vastly different outcomes.’ John Butcher, 2009

I enjoyed reading and viewing this piece. The photographic image of the dog surrounded by misty landscape is compelling (I’ve seen it before but can’t recall precisely where or when) and particularly, the connection, for a moment, between photographer and subject – the latter seems to convey the impression that the photographer may be friendly, is at least what I feel. I can recall how I felt myself around the age of 50 too, and relatively, it’s not that long ago. I am interested that David Sylvian was interested in investigative science, evidence based, at this time, which is a total parallel with where I find myself, today.

After finishing reading, viewing and listening to the audio clip, I felt compelled, particularly as I hadn’t for a while, to visit David’s official site. I was delighted to find that he was active in the art direction of published work that only became available a couple of weeks ago. This includes (further) photography by him and written work by another. Thank you VB, and I wish you and all the readership, the compliments of the season.

LikeLiked by 1 person