‘There have been exceptional times when making music hasn’t been possible,’ reflected Ryuichi Sakamoto in a 2018 interview. ‘Right after 9/11, for example, I couldn’t make any music for a month. The same happened after the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan, in 2011. And, obviously, when I got cancer, too. Otherwise, yeah, every single day I listen to music, think about music, play the piano and the synthesiser and I get through cups and cups of coffee.’

The events that paused Sakamoto’s creativity were of profound national, international and personal significance. ‘The tsunami and earthquake and disease, they made me think about life and death. The huge tsunami destroyed part of our civilisation, so we were warned about how our civilisation is fragile and how the force of nature is great. Also, the much more intimate thing about the cancer… It made me think very deeply about life and death – naturally. Our body is part of nature. Our creations, they’re not natural. We build things that aren’t natural, but our bodies, they’re part of that system.’

In the aftermath of the disaster in Japan, Ryuichi directed his energies towards projects that sought to help those directly impacted. He was particularly concerned with the consequences of the resulting nuclear incident at Fukushima which saw radioactive contaminants released into the atmosphere and resulted in more than 150,000 local inhabitants being displaced. ‘Many accidents happened in Japan. I started some charity projects and those are still ongoing. That made me very busy.’

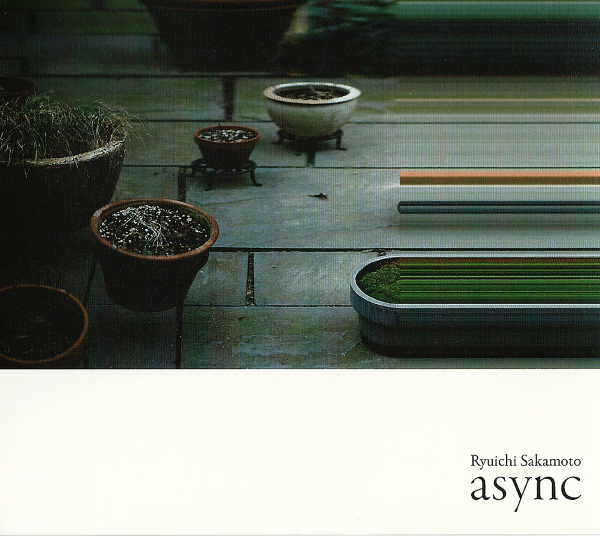

Thoughts were returning to music when his own health meant that the priority must rather be his own well-being. ‘I was going to make an album in 2014, the year I was diagnosed with cancer. I cancelled everything, and then two years later, I started making this album [async], and I decided to forget everything and dump everything I had at that point. I wanted to start from scratch, because I was the closest to death I’d been in my life. This was an important experience, and I wanted to dig into that experience.’

It was a time to reassess everything. ‘I studied Western music for a long time, ever since I was ten or eleven. I started taking piano lessons when I was six years old, and I also did composition techniques and the history of different styles from Baroque to contemporary music. For this album, I tried to forget everything I’d learned,’ he declared.

‘I didn’t know how or what I wanted to make. For a long time, I felt like a painter looking at a big blank canvas and not knowing how to paint. I kind of enjoyed that time though; it was like a big gift. For almost forty years I’ve been so busy working on so many things at the same time, so this was almost like the first time it felt luxurious, like I could do nothing and just look at the blank canvas. But then I had to actually start. I opened up my ears, collecting sounds I liked, inside and outside in the world, for four months. Soon I got tired of hearing New York noises and went to Paris, Kyoto, upstate. There are some sounds I just like as sound objects, but others generate musical emotions, so I was looking for elements inside these objects to help develop a piece.’

The liner notes for async reveal that as well as desiring to ‘collect the sounds of things and of places – of ruins, crowds, markets, rain…’, another key approach for the project was to ‘try making music whose parts and sounds all have different tempos.’ This concept of asynchronism gave the album its title.

‘99% of the music in this world is in synch, or strives to be. It’s human nature. We have a tendency to synchronise. We fall into line without even realising it. It seems we’re actually creatures that find pleasure in being in synch. That’s why I wanted to create untraditional music that doesn’t synchronise. Creating music that doesn’t synchronise is like speaking in a language that doesn’t exist.’

The track ‘ZURE’ is a case in point, where two deliciously warm analogue synth notes start as one but drift uneasily apart, then being joined by an electronic pulse marking a beat entirely of its own. As the track ends, we listen to disembodied piano notes and snippets of field recordings, left to ponder whether there is a line that differentiates ‘sound’ from ‘music’?

Two prominent voices are heard on async: that of the author Paul Bowles, and later the familiar tones of David Sylvian.

Asked whether there was a track on the album that was particularly personal to him, Sakamoto responded, ‘They’re all personal, but my big attachment is ‘fullmoon’, which starts with the voice of Paul Bowles. Did you recognise his voice? He already passed away, but he was one of the greatest 20th century American novelists. [Bernardo] Bertolucci made a film based on the novel, The Sheltering Sky. The author himself was in the film at the beginning and the end. He himself narrated an excerpt of the novel at the very end. That’s the voice I used for ‘fullmoon’.’

Sakamoto, of course, composed the soundtrack for The Sheltering Sky (1990) and was awarded a Golden Globe for the Best Original Score. ‘The first time I heard that voice and watched the final scene, it struck me very much.’

‘Because we don’t know when we will die, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens only a certain number of times, and a very small number really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, some afternoon that is so deeply a part of your being that you can’t even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five times more, perhaps not even that. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless.’

‘Obviously the text is so heavy and serious about life and death, and that excerpt is right after the husband dies in the middle of the Sahara, in the middle of nowhere. The quote in Bowles’ voice sounds something very profound to me: it’s not too dark, it’s very light; it doesn’t sound too serious, the way he expresses it. I like that balance. So for a long time, I wanted to do something with that recording, but I was not sure I could make good music with it.

‘Then, this time, for making the async album – because after the cancer, I thought this could be my last one – so I thought I should do everything that I wanted to do. So I asked Bertolucci to use that recording. He replied immediately, “Go for it.” So I listened to it many times, put [on] a sound, and listened to it over and over. Thinking what I needed more than that? Just a drone and his voice, looped. It sounded very nice. So what do I need? I was waiting for some weeks, for any idea to come.’ Bowles’ voice rises above the sound of a glass bowl resonating at the steady circular motion of human touch, the words he speaks a counterpoint to a ringing that seems to have the capacity to continue without decay.

‘Finally, I thought it would be nice to hear the same text but in Russian – because I love [Andrei] Tarkovsky. Although I don’t understand Russian, I like the sound. Then, I love Chinese movies, so why not Chinese? Then gradually I added some others. Luckily, I had a Russian friend here so he did it. Lots of friendly connections spread to many different countries, so those people [in the latter half of ‘fullmoon’] are basically my friends or friends of friends. Somehow they are all artists, writers, musicians. The German is spoken by my friend Carsten Nicolai. The Persian language Farsi is narrated by Shirin Neshat, who is an Iranian artist. By the [end], we got Spanish, French, German, Farsi, Icelandic, Chinese, Russian — why not Italian? For Italian narration, I should ask Bertolucci first, otherwise he will be mad [laughs]. So I wrote another email to him and explained that I wanted him to read Paul Bowles’ quote in Italian, okay? And he did it. Amazing.’

The result was intensely satisfying. ‘It’s gorgeous, so beautiful to me.’

The influence of film-maker Andrei Tarkovsky extended much deeper across async than prompting the Russian language on ‘fullmoon’. ‘I said to myself, maybe I should go with this idea of making a soundtrack for an imaginary Tarkovsky film, a film that only exists in my brain. It was impossible to imagine a completely new Tarkovsky film, so it was more an accumulation of memories of his existing films. It’s not just the stories but also the memory of one cut or one scene or just the images and sounds picked up from his work. Ever since I saw Tarkovsky’s films for the first time in the eighties, I’ve thought about his themes.

‘I didn’t specifically watch Tarkovsky films for this album, but I am a long-time fan of his films. He only left seven masterpieces, and I have watched them again and again throughout my life, but recently I like his films more than before, maybe because of age, maybe the disease. Maybe my experience with cancer is more related to the concepts of his films – life and death and memories. His films are full of poetry. There’s one, very biographic movie called Mirror. It’s very poetic and there’s almost no story, but it’s all about his imagination and his memories.’

Mirror has a famously non-linear narrative, switching throughout the movie between pre-war, wartime and post-war scenes from the life of the protagonist, Aleksei. Original newsreel footage is also interlaced with the scenes that Tarkovsky directed. One such excerpt provided a pivotal moment in the film. ‘I had to look through thousands of metres of film before hitting on the sequence of the Soviet Army crossing Lake Sivash; and it stunned me,’ recalled Andrei Tarkovsky in his book Sculpting in Time. ‘Here was a record of one of the most dramatic moments in the history of the Soviet advance of 1943…When, on the screen before me, there appeared, as if coming out of nothing, these people shattered by the fearful, inhuman effort of that tragic moment of history, I knew that this episode had to become the centre, the very essence, heart, nerve of this picture…

‘The scene was about that suffering which is the price of what is known as historical progress, and of the innumerable victims whom, from time immemorial, it has claimed. It was impossible to believe for a moment that their suffering was senseless…Once imprinted on the film, the truth recorded in this accurate chronicle ceased to be simply like life. It suddenly became an image of heroic sacrifice and the price of that sacrifice; the image of a historical turning point brought about at incalculable cost.’

The footage captured both a moment of enduring historical significance and the last moments of ‘simply people’ regarding whom Tarkovsky commented, ‘hardly anyone survived.’ Accompanying the images was the recitation of a poem in Russian by the director’s father. ‘The images spoke of immortality, and Arseny Tarkovsky’s poems were the consummation of the episode because they gave voice to its ultimate meaning…’ ‘Death does not exist. Everyone’s immortal.’

The piece read during that scene was called ‘Life, Life.’ For Ryuichi Sakamoto’s soundtrack to an imaginary Tarkovsky movie, words from another poem by the director’s father were incorporated, on this occasion read in English translation ‘by my good friend David Sylvian,’ for a track itself called ‘Life, Life’ – most probably a nod to the title of a collection of Arseny’s verse, and certainly thematically appropriate. The deadened sound of pizzicato strings is the prelude to the text:

‘And this I dreamt, and this I dream,

And some time this I will dream again,

And all will be repeated, all be re-embodied,

You will dream everything I have seen in dream.

To one side from ourselves, to one side from the world

Wave follows wave to break on the shore,

On each wave is a star, a person, a bird,

Dreams, reality, death – on wave after wave.

No need for a date: I was, I am, and I will be,

Life is a wonder of wonders, and to wonder

I dedicate myself, on my knees, like an orphan,

Alone – among mirrors – fenced in by reflections:

Cities and seas, iridescent, intensified.

A mother in tears takes a child on her lap.’

‘I’ve been reading Arseny Tarkovsky’s poems for a long time,’ said Sakamoto, ‘but this poem is about life and dreams, so naturally it sounds very charming and interesting to me after cancer.’

Images of recurring dreams, waves crashing unerringly on the coastline, and the reassurance of passing generations all emphasise continuity as one event passes in favour of the next, each a part of life itself, the ‘wonder of wonders’. ‘This recording of the poem by David Sylvian was actually made right after the big tsunami and earthquake happened in Japan in 2011,’ Ryuichi shared. ‘So David sent me around ten recordings of Arseny’s poems and I used maybe three of them for a charity concert for Japan around that time.’ (See ‘Concert for Japan’.)

There was a significant parallel between Sakamoto’s appreciation for cinema and developments in his music-making. ‘Nowadays, I like movies with a lot of silence and a lot of quietness. Tarkovsky, Robert Bresson, Ingmar Bergman – they’re generally very slow and they’re not overly expressive. There’s a lot of space in between, so you can go deep into the cinematic language or into the story. In music, when you have a lot of space you can have enough time to enjoy it and we can check the colours and shapes between the notes and the depth of the sound. So I think it’s very important for me to have space in between objects.’

He was aware that his own work had become quieter and more spacious. ‘It has been getting less dense since maybe 2000. For composition and for performance, for playing, too. Almost ten years ago, when I was touring, I played some concerts in London. A friend of mine, Dai Fujikura, who is a very successful contemporary composer – like Pierre Boulez loved him very much – knew almost all the music I’d made in the past. He grew up with my music. He knows it more than I do.

‘After the concert, we started talking, and he complained that I played much slower than the original songs or pieces. He asked, “Why?” That made me think, “Why do I want to play much slower than before?” Because I wanted to hear the resonance. I want to have less notes and more spaces. Spaces, not silence. Space is resonant, is still ringing. I want to enjoy that resonance, to hear it growing, then the next sound, and the next note or harmony can come. That’s exactly what I want.’

Ryuichi’s theme for The Sheltering Sky was a case in point, markedly slowed in his later piano performances when compared with the original. On async, both ‘fullmoon’ and ‘Life, Life’ boast spare clusters of piano. ‘I was coming to think the decaying and the disappearance of the piano sound is somehow very much symbolic of life and its mortality. It’s not sad. I just meditate about it. Also I have a longing for sustaining sounds such as violin or organ. Is it too simple to say those sustaining sounds symbolise immortality?’

Intriguing elements in the ‘Life, Life’ arrangement include a performance on shō – a type of Japanese mouth-organ – by Ko Ishikawa, and a vocal part by Luca Delphi that by her own admission resembles ‘the sound of a synth.’ There are field recordings too. ‘When I was looking for objects to record, I remembered seeing the Baschet Brothers’ sound sculptures at the Osaka Expo in 1970. I found them in a university building in Kyoto, and on a hot summer day, they let me record the sculptures in the sweltering heat amidst echoes of cicadas.’

With async so rooted in thoughts of life and death, an interviewer asked Sakamoto whether he aligned himself with any major religion?

‘No,’ came the reply, ‘but I’ve been interested in Tibetan Buddhism for a long time, since the early ’90s. I met His Holiness the Dalai Lama three times. Personally, face-to-face — well, with some guards [laughs]. He’s an amazing person. When I made my first and only opera called Life in 1999, the end of the 20th century, I really wanted to have a message from His Holiness. I wrote a letter, several times. And finally, I got a letter from his office saying on [a specific] day at one o’clock, come to Leh. Leh? What is Leh? Obviously, Leh is a city of the Kashmir region of north India. I had never heard of Leh, and found out it’s one of the highest cities — 4,000 meters from the sea level in the Himalayas. So come to Leh on that day at 1 p.m.! [Laughs.]

‘I couldn’t believe it, but I did it. So we were very nervous and waiting in the waiting room, then His Holiness came into the room, and I felt like some light was coming out from him, like a Jesus. “This is him, this is the man,” I felt — not I thought, but I felt it — some aura or light coming from him. If I am Matthew or Paul or John, and I put down my fishing nets and just started following him. I wrote about this to [David] Sylvian, I said I was like John when he saw Jesus coming on the street. “Why didn’t you do that, just follow him?” Sylvian said.

‘He’s an amazing person, and I hope and pray for his long life.’

Not long after async‘s release there followed an album of reinventions of the tracks by the likes of Alva Noto, Fennesz and Jóhann Jóhannsson. It was a testament to Ryuichi’s love of collaboration and deep appreciation for the skills of other musicians. ‘I am interested in someone who has a different talent, different set of ideas, different visions to me. If someone had the same talents, skills, ideas, visions, why would I work with them? I want opposition. I want difference.

‘So it’s interesting to listen for my elements in the tracks on async Remodels. The Arca remodel [of the title track], for example, I was trying to find my sounds somewhere in there, modulated, or pitched down, and I couldn’t. And that’s great! It is 100% Arca’s music. I enjoyed that. A remix is a different mix. These aren’t that. They’re reconstructions of music with some elements from my album. These remodels are like reflections. It’s a mixture of my music and their skills and ideas and palettes. I get to enjoy that my album inspired them.’

The version of ‘Life, Life’ on the album release of async Remodels was created by British electronic musician Andy Stott. For this rendition, Sylvian’s recitation of Arseny Tarkovsky’s poem is absent, with prominent beats introduced and a synth signature line that is directly in the spirit of Sakamoto’s original album.

Many may have missed that in 2018 there was an official online-only release of another remodel of ‘Life, Life’, a digital single to coincide with the launch of aysnc Remodels outside of Japan. This version was created by LA-based Brian Allen Simon who records under the name Anenon. His album Tongue came out around the same time, and the tracks ‘Open’ and ‘Mansana’ from that release make excellent companions for his ‘Dream Mix’ of ‘Life, Life’, in which Sylvian’s voice is encircled by swirling mists of synth and saxophone. It’s a reconstruction of the track that is well worth seeking out, ending poignantly with the phrase: ‘I was, I am, and I will be.’

Just after this article was first published, Brian told me a little more about his assignment to reimagine the track. ‘It brings me back to 2018 when I listened to async over and over again,’ he said. ‘‘Life, Life’ with Sylvian reading Tarkovsky is about as good as it gets. Anyway, the remix was commissioned by Milan Records around the time of Tongue being released, but I recall that the physical version of the …Remodels had already been produced when they asked me to do it…I spent a week straight working on the remix with many drafts, and the final version was perhaps the most straightforward and simple….I’m glad you enjoy it.’

Sylvian was asked about Sakamoto when his rendition of Arseny Tarkovsky’s poem was released on async. ‘He has a restless curiosity and might’ve been seen as something of a jack-of-all-trades, if it wasn’t for the fact that he’s a master of so many of them,’ he told the New York Times. ‘async,’ David added, is a work that ‘sings of mortality. It expresses a love and gratitude for life accompanied by the knowledge of its fragility.’

This article is dedicated to the memory of Ryuichi Sakamoto, 17/01/1952-28/03/2023, on the first anniversary of his passing. Thank you for the gift of your music.

‘Life, Life’

Ko Ishikawa – shō; Luca [Delphi] – vocals; Ryuichi Sakamoto – all other instruments; David Sylvian – spoken word

Music by Ryuichi Sakamoto. Words by Arseny Tarkovsky.

Contains poetry ‘And this I dreamt, and this I dream’ by Arseny Tarkovsky from Life, Life, used with permission by The Estate of Arseny Tarkovsky

Elements of the track recorded at Kyoto City University of Arts

From async by Ryuichi Sakamoto, Milan, 2017. Produced by Ryuichi Sakamoto.

‘Life, Life (Anenon Dream Mix)’

Brian Allen Simon – additional instrumentation

Released online, Milan, 2018

All musician quotes are from interviews in 2017/18. Full sources and acknowledgements can be found here.

Download links: ‘The Sheltering Sky’ (Apple), ‘ZURE’ (Apple), ‘fullmoon’ (Apple), ‘Life, Life’ (Apple), ‘Life, Life (Andy Stott Remodel)’ (Apple), ‘Open’ (bandcamp), ‘Life, Life (Anenon Dream Mix)’ (soundcloud), ‘Mansana’ (bandcamp)

Physical media: async (Amazon); async – Remodels (Amazon); Playing the Piano 12122020 (Amazon), Tongue (bandcamp)

The reading by David Sylvian is from Life, Life, Selected Poems by Arseny Tarkovsky, translated by Virginia Rounding, Crescent Moon Publishing, 2000, which is available to order here. © Virginia Rounding.

The 2018 Japanese release of the documentary Coda came with a second disc containing a live performance of async at New York’s Park Avenue Armory. This includes a live version of ‘Life, Life’ incorporating David Sylvian’s recorded spoken word part. The performance was subsequently also included on a US release (see here).

In 2023 a site-specific installation based on async was staged in the basement of the Kyoto Shimbun Building. Earlier this year async – immersion 2023 was released in digital format, being a unique mix that blends the ambient sounds of the exhibition space – a former printing factory – with Sakamoto’s original compositions. This includes ‘Life, Life’ featuring David Sylvian (see here).

‘Music is endless, it’s limitless, and there is no limitation on imagination.’ Ryuichi Sakamoto, 2018

Related articles:

Always speechless in front of your innate aptitude to distill knowledge, memories, experience and feelings in these concise yet so focused essays. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for the feedback.

LikeLike