Robert Fripp’s online diary, 20th October 2004:

‘Today’s work in London is a recording session for David Sylvian’s new solo album. Eden Studios is conveniently just around the corner from the bijou Chateau de Petite Chevalle [an affectionate reference to the Willcox/Fripp residence in Chiswick, just north of the Thames in London].

Today’s session: for me, a treat. David & his brother Steve were both waiting when I arrived…’

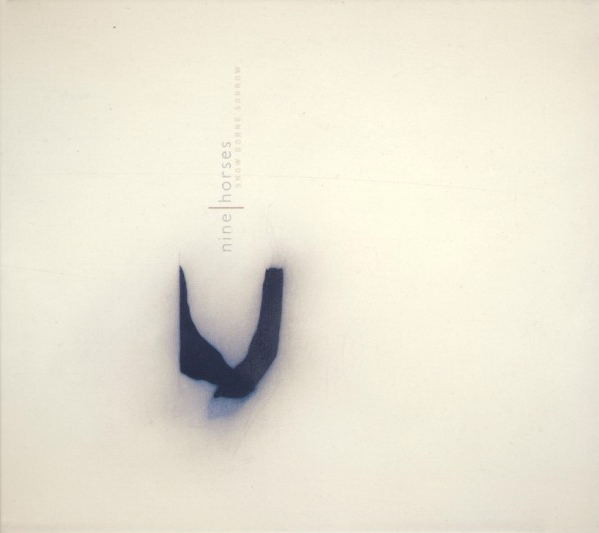

In fact, the studio was booked to capture some final performances to embellish the tapestry of mixes for the debut release of Nine Horses, the trio in which Sylvian shared equal billing with Steve Jansen and Burnt Friedman. Fripp continues:

‘Standard Operating Procedure: I overplay, to give a plenitude of material & phrases for cutting, pasting, re-arranging, sampling, (sometimes) leaving as they are, and a lot for discarding. The piece: a wonderful, classic, gorgeous Sylvian ballad.

Several firsts on this session:

PodPro rackmount as the effects unit; no echo or reverb on either effects or monitoring; nearly all my playing with the thumb.

Not a first, but for the first time in over thirty years: soft “modern” chords (that’s what they were called when I was learning them in the early 1960s). “Giles, Giles & Fripp!,” called out David.’

The evident enthusiasm for the challenge lies somewhere in the jeopardy of the situation…

‘At a session, there are no laurels and no past achievements to rest upon: however good a recorded solo from history might be, today you deliver or not. And if you don’t, your professional future is in doubt. A session is always a challenge, always a pointed stick, particularly when re-visiting a former collaborator of good work.’

That day was a first for Steve Jansen too, even though he had been previously heard playing alongside the guitarist on both Gone to Earth and ‘Steel Cathedrals’: ‘I didn’t meet Fripp on any Sylvian recordings because we worked at different stages in the making of the record. In fact, I hadn’t met Fripp until he worked on the Nine Horses album at David’s request and he was a pleasure to work with, never for a moment deterred from exploring various ideas and providing a wealth of alternative takes.’ (2017)

Theo Travis also received the call to Eden that day. The virtuoso woodwind player had linked up with Jansen, Richard Barbieri and Mick Karn back in 1997 for a short series of live dates in a band that also numbered Steven Wilson amongst its ranks, including a truly memorable night at London’s Astoria. It was a gig that led to Theo’s involvement in a host of projects in a related constellation of musicians including Yukihiro Takahashi, Masami Tsuchiya, Anja Garbarek, Indigo Falls and Porcupine Tree.

The invitation to contribute to Snow Borne Sorrow ‘came from Steve Jansen who was one third of the Nine Horses band,’ Theo explained to me. ‘I knew Steve well since 1997 and he rang me up one day in 2004 and asked if I was free to come to a recording session for David at Eden in West London.

‘I remember the recording session very well. Robert had been in the studio recording a guitar solo; I understand he was in the morning of the day I went in in the afternoon. Steve was present and was an equal partner in the direction during the session. Burnt wasn’t there.’ This was Theo’s first time working with David Sylvian. ‘I knew Brilliant Trees and the Rain Tree Crow album. I think I might have heard Gone to Earth too, but not others. I was very aware of him, especially having been around Steve, Mick and Richard so much since 1997.

‘As far as I remember I had not heard the tracks before I arrived at the studio, so heard them for the first time when I got there.’ The original multi-tracks put together by Burnt Friedman already included woodwind parts from both Thomas Hass and Hayden Chisholm, but Jansen and Sylvian were looking to supplement this this with something different…

‘For ‘Banality of Evil’ I don’t remember any discussion about the lyrics at all, but there was talk of the sort of approach to take. I think I remember David and Steve saying they wanted to do things that were not the expected sounds, and go for a more unpredictable approach. Choosing the tenor sax was one such choice. I remember Steve saying that what they wanted me to try was something a little “out”, like Ornette Coleman or something like that – not bluesy or obvious at all. I recorded a few takes like that. Then Steve asked for something very “far out”!

‘I had recorded these pretty free improvisations on the track and he asked if I could try and play something in harmony with those but in a different time feel. Crazy stuff!’

Many of the songs on the album were rooted in unusual metre. An inquisitive interviewer asked Sylvian to confirm his conclusion that ‘The Banality of Evil’ was in 10/8 time. Sylvian laughed, ‘You know what, there are a couple of tracks on the album which were written by Burnt Friedman – and that’s one of them – which he created in very strange time signatures and originally they had drum patterns by Can’s drummer, Jaki Liebezeit. And so these tracks were really in rather complex rhythms and timings, and then Steve, my brother, replaced the original drum patterns and sometimes he would change the time signatures completely as well. So, at this point of time I’m confused as to where we sit with ‘The Banality of Evil’!’

Sylvian confessed to adding what the interviewer described as the ‘lower retuned guitar that goes “dow-dow-dow”ʼ, his host surmising that this enabled the count of 9-10-1 as an anchor for the vocal. How could he possibly sing with such unfamiliar rhythms? ‘I have never counted in my life while I’ve played music, it’s purely intuitive…I can’t possibly count while I’m singing. It has to just make sense to me and when I heard these pieces that Burnt had created, the melodies immediately fell into place. They just kicked into place wherever I felt I was comfortable with them – which wasn’t always where Burnt had intended me to sing and in the time signature that Burnt had intended, but he allowed me that freedom.’ (For more on Burnt Friedman and Jaki Liebezeit’s fascination with non-Western rhythms, see ‘The Librarian’).

‘At the very end of the track,’ Theo Travis continues, ‘you hear this multiphonic saxophone sound that is pretty wild and in a key different to that of the song, but it works in its own way. What was really wild was that in the mix it was again decided to leave multiple saxes in at the same time.’ The exact same thing had happened with ‘A History of Holes’, where Travis had been amazed to find on hearing the final disc that his various takes had been edited together so that he accompanies himself many times over (read more here).

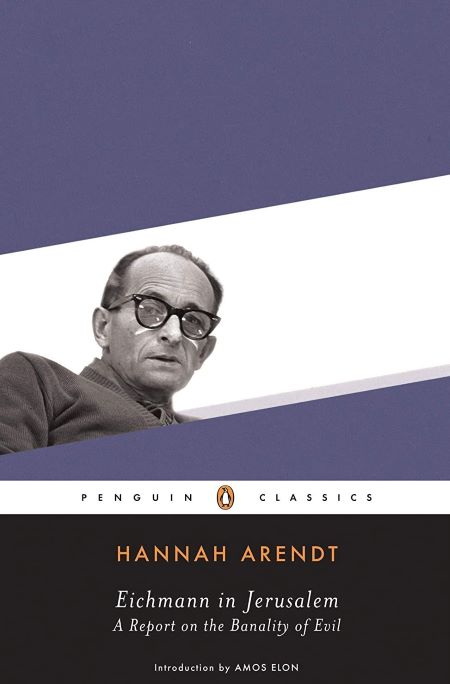

The title of the track is a reference to Hannah Arendt’s book on the trial of German Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann, entitled Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Eichmann was one of the principal organisers of the horrors of The Holocaust, what the Nazi’s referred to as ‘The Final Solution to the Jewish Question’. He facilitated much of the logistics involved with the mass deportation of Jews. Captured in Argentina in 1960, he was subsequently found guilty of war crimes at trial in Israel where he was executed by hanging in 1962.

Arendt observed that Eichmann ‘lost the need to feel anything at all. This was the way things were, this was the new law of the land, based on the Führer’s order: whatever he did he did, as far as he could see, as a law-abiding citizen. He did his duty, as he told the police and the court over and over again; he not only obeyed orders, he also obeyed the law.’

The most atrocious and despicable acts were perpetrated by a seemingly ordinary man carrying out what his superiors required of him to the best of his ability and in pursuit of his own professional advancement. Arendt’s book caused significant controversy and future editions carried a ‘Postscript’ in which the author addresses some of issues raised by critics. She says:

‘I also can well imagine that an authentic controversy might have arisen over the subtitle of the book; for when I speak of the banality of evil, I do so only on the strictly factual level, pointing to a phenomenon which stared one in the face at the trial. Eichmann was not Iago and not Macbeth, and nothing would have been farther from his mind than to determine with Richard III “to prove a villain.” Except for an extraordinary diligence in looking out for his personal advancement, he had no motives at all. And this diligence in itself was in no way criminal; he certainly would never have murdered his superior in order to inherit his post. He merely, to put the matter colloquially, never realised what he was doing. It was precisely this lack of imagination which enabled him to sit for months on end facing a German Jew who was conducting the police interrogation, pouring out his heart to the man and explaining again and again how it was that he reached only the rank of lieutenant colonel in the S.S. and that it had not been his fault that he was not promoted…It was

sheer thoughtlessness – something by no means identical with stupidity – that predisposed him to become one of the greatest criminals of that period.’

In this context, Sylvian’s opening lyric chills to the core in its description of menacing authority bestowed by dint of a uniform:

‘I got me a badge

A bright shiny badge

I’m painting the crest in yellow and blue

I’ve got me a club

An exclusive club

It doesn’t include a place for you

Hey, hello neighbour

Hey, hello neighbour, right you are’

There is ridicule in the language, but it signals a dangerous truth: how can a ‘bright shiny badge’ of ‘yellow and blue’ confer authority to one person over another?

The pretence calls to mind Sylvian’s immediate response to 9/11 (see ‘World Citizen’-‘Chain Music’) when he wrote that, ‘To give in to the propaganda perpetrated by both sides of this conflict that perpetuates this sense of “otherness” where the “enemy” is concerned is to enable us to distance ourselves from the crimes against humanity executed in our names.’ Surely greater principles are at play than a nationalistic agenda? Namely our common humanity, united – as Sylvian described it – by ‘the spark of divinity [that] resides in all beings.’

The “otherness” he speaks of is embodied here in a world-view that devalues anyone who is not the same as “us”:

‘I don’t believe in what you believe

Your skin is filthy

And your gods don’t look like God to me’

There are words in this song that make my skin crawl. They imply a flicker of recognition as to the humanity of the enemy, but the greater hint is towards the violation that too often in history has accompanied the conquering of physical territory and subjugation of a native people. And the perpetrator’s implication is that the fault lies with the abused:

‘But I want to touch you

Now that isn’t right

No, that can’t be right

But I want to touch you

You’re leading me on, I know it’

The blasé attitude that comes with unbridled power is caricatured, but this is more sinister than satire:

‘King of the castle

Room at the top

Off with their heads

Chop ’em off’

In a link with Eichmann’s declarations at his trial, ‘the perpetrators are in denial’; but the parallel phrase is also true, ‘the benefactors are in denial’. Do we have our eyes open wide enough to see whether we are the unwitting beneficiaries of cruel abuses of power?

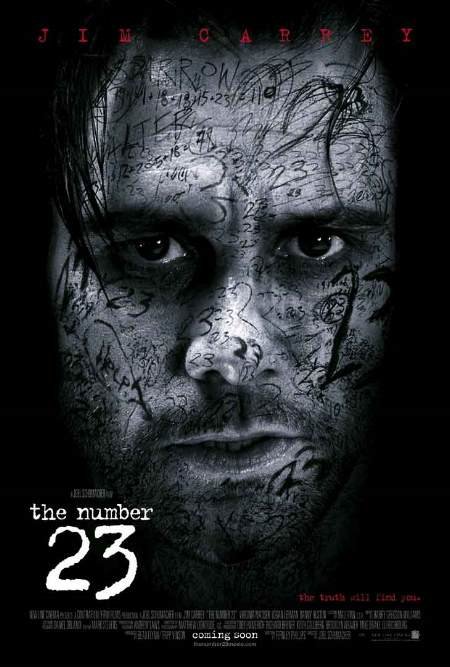

The song’s atmosphere and theme led to its use in another context. Theo Travis recalls, ‘I was on a plane on tour some time later and I saw the Jim Carrey film The Number 23, which is a pretty cool film – quite dark. Over the closing credits the track ‘The Banality of Evil’ plays including the end sax solo. It was a surprise and a thrill hearing that. It is a great track and I am proud to be on it.’

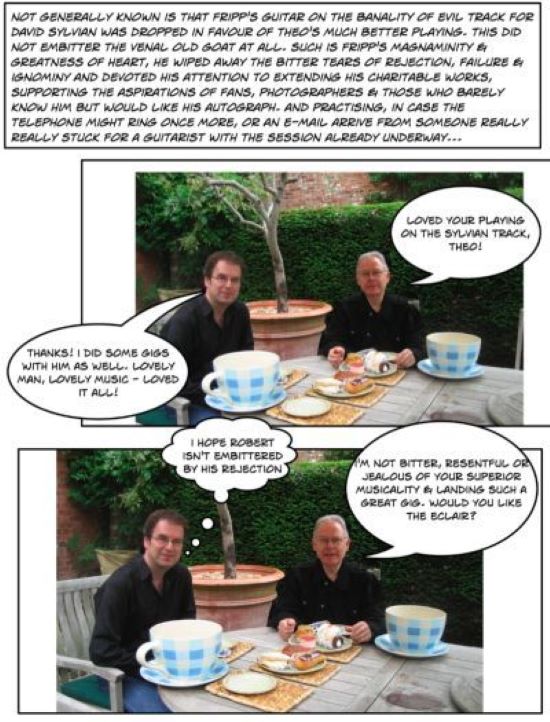

The fact that Robert Fripp was involved with the Snow Borne Sorrow sessions emboldened Theo to approach him about a contribution to a solo project he had underway. ‘It was because we had both been invited to record for this album – and also I was a friend of Steven Wilson and Robert had just been on tour with Steven playing a solo soundscapes support slot for Porcupine Tree – that I thought it would not be out of place for me to get in contact with Robert, as I wanted to propose the idea that he contribute some playing to an album of mine I was working on – Double Talk. It seemed that I was nearer his “orbit”. I wrote to Robert and introduced myself, and he e-mailed back to say that he knew who I was as David Sylvian had chosen my solos over his on the Nine Horses album! That was embarrassing and made me feel very awkward indeed. We did laugh about it later though…’

The episode was immortalised in another entry in Fripp’s diary:

‘Apart from the awkwardness surrounding the solos for the ‘Banality of Evil’, Robert asked to hear some music of mine and then asked if he could come and hear me play live. I sent him my Slow Life album, which he later said he enjoyed. He then came as a guest to a Soft Machine Legacy gig at the Pizza Express, Soho in London. That was February 2006. He came along, listened to the gig, and we chatted. Robert seemed to approve of my playing and said he would contribute a soundscape for my recording. I went to the DGM studio in Wiltshire in January 2007 and Robert recorded the soundscape for me.

‘When that was done we had time left, so I suggested we record some improvisations together. He said yes, so I set up in the studio. In the two hours that followed we had recorded enough music to make the entire Travis & Fripp Thread album.’

Thread was my introduction to the music that Theo and Robert have made together; it was incredible to learn that it was borne out of an impromptu footnote to another project. We have never heard Fripp’s guitar crafted for Nine Horses – nor, intriguingly, another track that he referenced in his diary entry that day: ‘here at DGM, David Singleton is presently editing a demo of The Vicar’s to be submitted to David Sylvian for his consideration.’ However, a musical partnership was spawned which has so far resulted in the release of three studio albums and most recently a triple live-set.

‘The Unspoken’ and ‘Curious Liquids’ from Thread sit alongside ‘The Banality of Evil’ on my playlist. Less strident than the Nine Horses cut, but showcasing Theo’s playing and a pairing that might have appeared on record together earlier had Steve and David made different final editing decisions.

‘What I enjoy about creating music with Robert is multi-fold,’ enthuses Theo. ‘I love the sound we make together. I love the ambient soundscape world we both inhabit using loops and technology but keeping the music very organic and human. I like the way Robert uses harmony in his playing and it fits well with how I like to play melodically. I enjoy the “edge” to Robert’s music. It is not soft/new age or “light”. There is always a seriousness, a heart, a darkness and a depth to what he does – and you can hear it.

‘On a personal level there is a mutual respect and a symbiosis that works and is hugely enjoyable and rewarding. Finally, there is a great response from audiences who seem to “get” what we are doing and our music seems to resonate with people – sometimes deeply. Someone said they attended one of the concerts and afterwards went to their car to go home and just sat and cried from the emotion. I found that incredibly powerful.’

‘The Banality of Evil’

Hayden Chisholm – clarinet; Burnt Friedman – keyboards, editing, drum programming; Morten Grønvad – vibraphone; Thomas Hass – 1st saxophone solo; Steve Jansen – percussion; Rif Pike III – electric guitar; Carsten Skøv – vibraphone; Neal Sutherland – bass guitar; Theo Travis – 2nd saxophone solo; David Sylvian – guitars, keyboards, vocals; Marcina Arnold & Eska G Mtungwazi – backing vocals

Music by Burnt Friedman & David Sylvian. Lyrics by David Sylvian.

Produced and arranged by David Sylvian. From Snow Borne Sorrow by Nine Horses, Samadhisound, 2005.

Mixed by David Sylvian with Steve Jansen at samadhisound

lyrics © copyright samadhisound publishing

Many thanks to Theo Travis for his generous contribution to this article. Do check out Theo’s bandcamp page and website.

Robert Fripp’s diary can be read at the DGMlive website here. Thank you to DGM for their permission to use excerpts and images in this article.

Full sources and acknowledgements for this article can be found here.

Download links: ‘The Banality of Evil’ (iTunes); ‘The Unspoken’ (burningshed); ‘Curious Liquids’ (burningshed)

Physical media links: Snow Borne Sorrow (Amazon); Thread (Amazon) (burningshed – vinyl)

‘I think Snow Borne Sorrow is one of the best albums I have ever guested on. It really holds up and I still love to listen to it. Great songs, great sounds, wonderful playing and skilfully and tastefully produced. David sings beautifully and, in my opinion, David and Steve are at their absolute best on it.’ Theo Travis, 2020

More on Snow Borne Sorrow:

Atom and Cell

A History of Holes

Snow Borne Sorrow

The Day the Earth Stole Heaven

Related:

The Librarian – Friedman & Liebezeit feat. Sylvian

Thank you for this. I appreciate the way you draw from various sources to form a coherent and interesting article. I learn something new every time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a spectacular flashback about so many intriguing figures that for years have truly been part of my life, not just in a musical sense. Your tesserae are precious milestones for the comprehension of the whole.

I owe you so much, David. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful piece, it would be interesting to hear a version with RF playing on it. A truly wonderful album from start to finish. I have been loving Robert n Toyahs Sunday lunch on you tube, such a wonderful endearing couple.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you again for another revealing post, this time about a favorite track. I had just re-watched the Hannah Arendt film from 2012 yesterday – amazing synchronicity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The cognoscenti of the modern music world, I hope that one day the musicians here are recognised by a wider public… We just need a Sylvian /Wilson collaboration to complete the circle.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Because Thomas Hass’ solo was a part of the original track that Burnt sent Sylvian he felt Travis had to match its character, forthrightness, and sense of freedom. The Hass original is a wonderful solo break. Sylvian suggested Coleman as a point of reference (He also selected Coleman’s Free Jazz (?) in his iTunes playlist and witnessed his final concert in London) so as to try to loosen up Travis’ approach to the piece. As a footnote, all editing of the Burnt/Sylvian compositions were executed by Sylvian.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you again for a fascinating insight. I agree with you about Hass’ solo. To confirm, Sylvian chose ‘Free Jazz (Parts 1 & 2)’ by Ornette Coleman on his iTunes curated playlist, writing: ‘What’s happening here is so complex, intense and full-on, but it’s also strangely accessible. Like finally settling down with a literary tome whose reputation you’ve always found intimidating and realising, “This is easy, I get this.” It lifts you and expands your horizons.’ Thanks for the reminder of that selection.

LikeLiked by 1 person