On 1 March 1982, an album simply titled Japan was released in the US by the band of the same name. A deal with the Epic label gave the group a tilt at the American market. Japan’s members were on hiatus at the time, taking a break after the tensions of the Visions of China tour in late 1981, a chance to pursue solo and other projects or interests. There was a UK TV appearance for the BBC’s Old Grey Whistle Test on 4 March, with ‘Ghosts’ and ‘Cantonese Boy’ played live to promote the former’s release as a single (see ‘Ghosts – live’) but this was a brief reunion among other endeavours. Steve Jansen, Mick Karn and David Sylvian contributed to Akiko Yano’s album Ai Ga Nakucha Ne, sessions taking place in London in February ’82 with Ryuichi Sakamoto producing. Then Sylvian and Sakamoto headed into the studio to fulfil a long-held ambition for a joint project, the fruits of which were ‘Bamboo Music’ and ‘Bamboo Houses’.

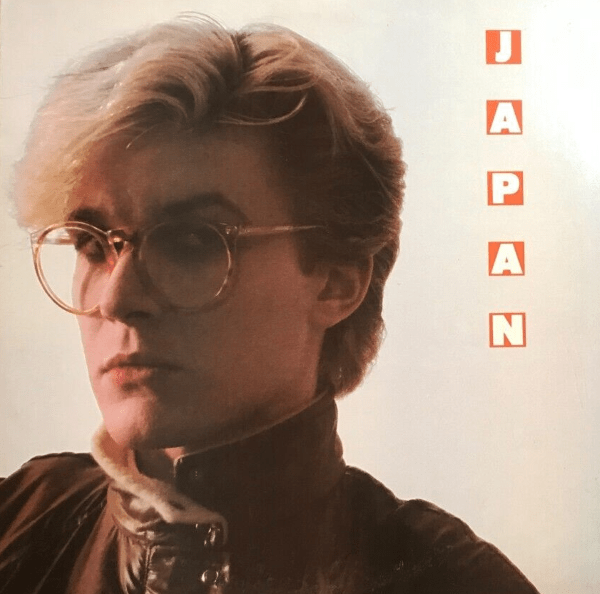

The release Japan set before American listeners was a rather odd amalgam of the band’s Tin Drum and Gentlemen Take Polaroids albums. The track-listing started with ‘The Art of Parties’ and ended with ‘Cantonese Boy’, consistent with the familiar Tin Drum running order, but here ‘Canton’ is replaced by the …Polaroids title track, with ‘Sons of Pioneers’ giving way to ‘Taking Islands in Africa’ and ‘Swing’. Compared with the craft of the sleeve designs for the band’s UK releases, the rather bland lay-out and shot of Sylvian chosen for the cover seemed uninspired to me, but I guess Epic knew how they wanted to present the record to their market.

David Sylvian professed to a lack of enthusiasm for pushing either Japan or his own music in the US but in April 1982 he did take the opportunity to visit New York for some promotional activities. On 20 April, Sylvian appeared on MTV. Far from the commercial pillar of mainstream music culture it is today, the channel was then a fledgling operation having only launched the previous August. Photographs from the TV set show Sylvian wearing a checked jacket and seemingly in confident mood. A photo session was also staged high above the New York streets.

Sylvian was particularly enthusiastic about being invited to be a subject for Interview magazine, founded in 1969 by Andy Warhol, also being filmed in conversation for Warhol’s cable TV programme and meeting the man himself on 23 April. He had long admired the American’s pop art, citing the famous ‘Campbell’s soup can’ images as inspiration for the hypnotic repetition incorporated into Japan’s music (see ‘Nightporter’).

Ultimately, the article for Interview remained unpublished and the footage for Andy Warhol TV was edited but never broadcast – although it can be viewed at the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and was screened there at a Warhol’s Unseen Television event in February 2024. Contact sheets in the Warhol archive show images from the pair’s meeting. Both seem smitten with the experience.

Later in the year Sylvian was asked by The Face magazine, ‘Is there anyone you admire and would especially like to meet?’

‘Andy Warhol was on the top of my list until I met him recently in New York…’ came the response. ‘You know that image he portrays, that of banality, like going along with everything that you say, everything’s great and wonderful? Well he’s not really like that, you can tell that there’s something deeper than that. Most people have the impression that he doesn’t speak very much, that he just responds to people’s questions in that “Yeah great” manner, but really he talks quite a lot and he’s a very interesting person.’

There was even talk of working on music together. The same publication separately asked Warhol: ‘Are you still working on some lyrics for the group Japan or did that all fall through?’

After gushing, ‘He was so cute. God, he was so cute. I really liked him a lot…’, when pushed about the lyrics, Warhol explained: ‘Well, because he went back to England and then he went to Japan it was sort of hard for us to get together. Anyway, it was only going to be one line.’

What was the line?

‘That’s what we were having trouble deciding’!

It so happened that when Sylvian was in New York for this whirl of engagements, an exhibition was being held at the Marlborough Gallery at 40 West 57th Street, just a couple of blocks from Central Park. Running from 2 to 30 April 1982, the show comprised recent portrait and landscape paintings, and chalk and charcoal drawings, by London-based contemporary artist Frank Auerbach. The Marlborough was Auerbach’s gallery with offices in both London and New York, and this was his first solo exhibition since 1979.

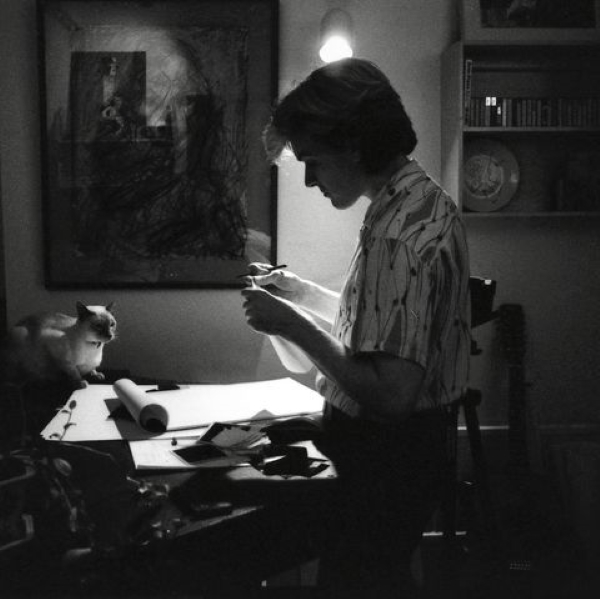

In David Sylvian’s introduction to the Japanese edition of his book Perspectives (1985), he writes: ‘In the early part of 1982 I had, for numerous reasons, decided to take a rest from songwriting. This was to be the first break I had had since I’d started as a child at the age of twelve. It was therefore not surprising that to relieve the subsequent frustration caused by this action, I turned to the only other creative outlet I’d known, and which had been my main preoccupation until my discovery of music, drawing.

‘The freshness brought on by this change, the naive pleasure of working and learning in a virtually unexplored area for me opened many doors.

‘Not least of which being my new found appreciation of the world of the arts. Drawings, paintings, sculpture, ceramics, a universe of creativity which had always been hidden from me, suddenly came to life. I had of course been aware of works by various famous artists before, but although I was able to appreciate a lot of what I had inadvertently seen, I had never felt anything emotionally from the work in the way that I could quite naturally feel from music. Now all was changed.

‘I first realised this whilst visiting a major exhibition by a painter living and working here in England, Frank Auerbach. The depth and intensity of emotion I experienced surpassed anything I had felt in music for a very long time, if at all. I explain this because through these and various other similar experiences my outlook on life and work changed (or maybe matured would be more appropriate) at quite a dramatic pace.’

The Auerbach show in New York included a series of portraits in oil of “J.Y.M.”, covering a period from 1976 to 1981, and five drawings of the same subject from 1980-81. Sylvian has described experiencing an epiphany when viewing one of Auerbach’s head and shoulders paintings of J.Y.M. ‘Well, I had a problem looking at visual art up until I saw that painting of Auerbach’s. I would walk around galleries, and I would appreciate the beauty of some of the work, the abstract nature, blah, blah, blah, but I was never moved. Not like a piece of music would move me or a poem.

‘So I was quite unprepared for the experience that I had with the Auerbach, and I can’t tell you what I did or if I did anything to prepare me for that experience. I was just open to that moment. I must have been in a very open state of heart and mind, and was just blown away by one particular image. And the experience was as intense as any experience I’d had in music, and that was exciting because I just didn’t think it possible.

‘And since that time I’ve had that experience on a number of occasions with a variety of different artists. And it’s just a matter of being open to the work and also giving the work time. If you’re going to go down to the Tate Modern, don’t try and see it all. Just think, “Well I’ll walk through all these rooms but I’ll stop in front of three works and spend some time with three that appeal to me and see how I get on,” and you’ll be amazed at what happens.’ (2001)

Sylvian has been quoted as saying that his visit to the Auerbach exhibition was in 1982. If so, the only such event that year was the one being staged when he was in New York. Notably, the painting that prompted Sylvian’s response, Head of J.Y.M. II (1980), is not specifically mentioned in the catalogue, although the subsequent Head of J.Y.M. III (1980) is there. A showing of the artist’s work at the Marlborough’s gallery close to London’s Royal Academy of the Arts in January/February 1983 did include Head of J.Y.M. II (1980). Perhaps Sylvian visited the Marlborough in London as a follow up to the New York event, or maybe his discovery of Auerbach’s work was slightly later than reported. What cannot be doubted is the impact of that work upon him.

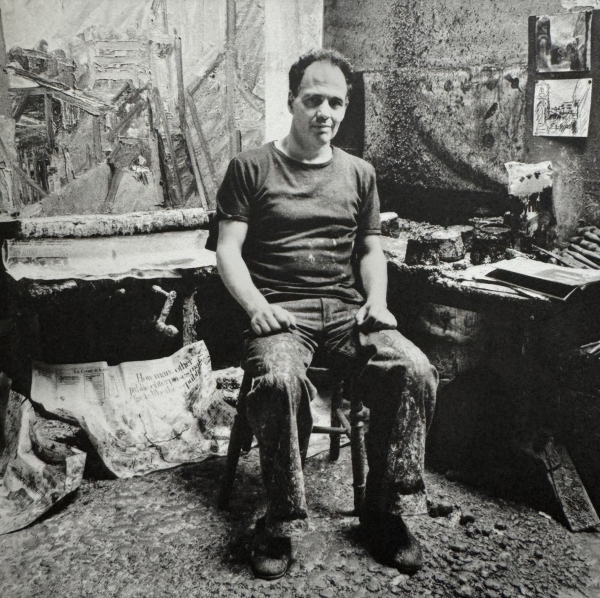

Frank Auerbach’s practice involved regular sessions with a small number of sitters, working and reworking the surface until the image for which he is striving emerges. Thick layers of oil paint are applied, scraped back and more re-applied, with each work taking months to complete. Seeing the original paintings rather than reproductions, as I was fortunate to do early in 2016 when attending the major retrospective of the artist’s work held at Tate Britain, you are struck by the three dimensional nature of their surface, which conveys something not only of the sitter but also of the physical act, perhaps the struggle, of their creation. These portraits, it seems to me, exist on the border between figurative and abstract art, conveying some essential truth about the sitter, as much about the sense of their presence as a specific likeness.

Auerbach said this of his daily discipline of painting: ‘I’m just having fun in the studio. I’d rather do that than go to the theatre or sit about…In the same way that people play games that have an element of intractability, something like chess, games with an infinite set of possibilities and difficulties. Or in the way that people perform a sport that doesn’t come naturally to them, or solve complicated puzzles. In that way, one does this immensely difficult, immensely challenging thing in the studio, with the added bonus that if one should finish something, which is relatively rarely, one surprises oneself. I can’t foresee the end of my pictures or my drawings. I keep on working, and trying to do them in the hope of finding this result which to me is surprising, more surprising than finding an Easter egg as a child.’ (1986)

Head of J.Y.M. II (1980), the featured image for this article, would find its place on the cover of Japan’s album Oil on Canvas. The picture itself and the title chosen for the record serve as representations of the creative act (albeit the title was not precisely accurate for the painting in question, since this was in fact ‘oil on board’).

oil on canvas, 16⅛ x 18 in. (40.9 x 45.7 cm)

‘…what one’s painting is one’s reaction to this human animal.’ Frank Auerbach.

The fanzine Bamboo followed up on the connection and pluckily interviewed Auerbach for a two-part feature published in 1987. The artist explained more about ‘J.Y.M.’ confirming, ‘Yes, it’s a woman!… J.Y.M. is a woman called Julia Yardley Mills, who was a model at Art School. About thirty years ago I taught at Sidcup and there was a very nice model who seemed to enjoy posing in difficult positions with total dedication. She said to me in a break, “If ever you want me to pose privately, I’d be glad to.” So, I took her up on it and over the years she’s become a friend, her daughter has grown up and had two daughters and she’s just been posing for me for twice a week ever since…

‘So J.Y.M. are her initials and I haven’t used her initials to be interesting… everyone knows her as JYM [pronounced “Jim”]…She’s been coming twice a week to pose for me and I’m immensely grateful, it’s been a lifeline. She’s totally dedicated, she’ll pose for five hours at a time and of course I became more and more interested the longer she’s posed. As you get to know someone, you see more.’

J.Y.M. is not to be confused with the Julia who is the subject of many other works by Auerbach, the latter being Frank’s wife, Julia Auerbach (née Wolstenholme).

The Bamboo interviewers commented that the painting had ‘a certain anguish to it,’ to which Frank responded, ‘I’m hardly conscious of these things, but she had an arthritic hip and she was in great pain. She finally had a hip operation and she’s perfectly alright now. But she kept on posing for me…people tell me that the paintings I did around that time do show the fact that she was in some considerable pain. But I just paint, I don’t put labels on things, but sometimes it comes across.’

So how was he approached about his work being on the gatefold cover for Oil on Canvas? ‘It was done through the gallery, but it was David Sylvian who wrote and they said to me, “Don’t suppose you want to do this?” and I said, “Yes! I very much do. I’ve always wanted to be on an album cover!” And then a while ago I met his girlfriend in a gallery and she said that she liked my work and he liked my work, so that’s why they put it on…[she] said that the painting meant a lot to him.’

Did Sylvian purchase the portrait in question? ‘No, but he did buy another picture of mine, it’s called The Head of Margaret Schuelein. The Marlborough have a photograph of everything I’ve ever done. I’m not very prolific, I only do eight to ten things a year. Everything I do goes to the Marlborough.’

And did the painter meet the musician? ‘No. I think he’s probably not unlike me and likes to get on with his work. I was pleased about it all. I also asked my son Jake, who’s fairly well into pop and he said he thought a lot of David Sylvian, he thought he’d go far. That was enough for me.’

In picking up pencils again during a period away from songwriting and performing, Sylvian rediscovered something about his creative impulse. Reflecting after the release of Brilliant Trees, he said, ‘I don’t think you can take my drawing very seriously from a critical point of view but it’s really good for me at the moment, it’s learning something else again. By drawing you also tend to see things differently and that helps the writing. I’m more observant than I was before, I see things clearly, I see pictures in many things that I may have been blind to before and I know that enriches my life and must, consequently, enrich my work.

‘The drawings and Polaroids gave me back a naivety that I’d lost – just starting from scratch again – and that tended to translate into the music. I thought “Yes, I used to feel that way about music, how can I get back to that?” I’ve always been influenced by visual things and recently it’s been paintings.’ (1984)

Frank Auerbach once said of his portraiture, ‘I’ve painted the same person thirty times…with someone one knows one’s got to destroy the momentary things. At the end comes a certain improvisation. I get the courage to do the improvisation at the end – a gaiety – a serious word.’ The immediacy and freedom in the brushstrokes of the completed work struck Sylvian deeply. He said of J.Y.M. II (1980), ‘It hit me in the same way music does … inside. There seemed to be a moment of inspiration between the painter and the canvas that you could see, a direct line running through it.’ (1986)

He began to think about how this ‘moment of inspiration’ could be transmitted into his music. ‘When Japan split up I wanted to get into something that had a bit more life to it, a bit more spontaneity to it,’ Sylvian told David Toop in their 1986 conversation. ‘It came out of conversations with Yuka to do with painting, which we both love and we go to galleries quite often. And it was particularly from the painter that did the painting on the cover for Oil On Canvas, Frank Auerbach.

‘We were just talking about how to get that sense of spontaneity, that sense of the presence of an artist. Like he makes a line, a sweep on the canvas, that you feel his presence in a picture and the emotion and the drama of that line. What’s the closest form of music that can do that, or comes close to that idea?

‘And we talked about it for a while and came to the conclusion that jazz and improvisation was the only form that could really come close to that, which is why I became interested in jazz and why I now feature soloists or give them quite wide scope on a lot of the pieces with Jon Hassell, Robert Fripp, Kenny Wheeler.’

David Toop: ‘It’s interesting that you make that parallel with painting because in the end painting is static, isn’t it? And there is a very static feel about a lot of your music. There is movement within it, but it’s static in a way that a lot of jazz isn’t – it [jazz] has a very dynamic movement and there is always the suggestion of change, whereas in the tracks that you do now, it’s almost like a frozen moment with movement within it. Do you think about that kind of parallel at all?’

David Sylvian: ‘I don’t think I really thought about it, I think that happens instinctively. I do like to put a frame around things. I do like photographs, that they capture a moment but the mood that they create changes with your mood, with the mood of the viewer. So they are static and at the same time they can create different emotions within you – paintings more so than photographs. The way that you just described my music sounds like a really good description of an Auerbach painting, there is movement frozen with a framework, that’s what’s visible.’

‘Oil on Canvas’ was not only the name given to Japan’s final album, but also to the brief introductory track. It was one of three instrumentals created by the band to muster an atmosphere around the representation of the band’s live show. Music to transmit a sense of what it might have been like to be in the audience. ‘Oil on Canvas’ is a piano and synthesiser piece written and performed by Sylvian alone. In the last act of the band, both the cover art and this slight and introspective composition pointed forward to an exciting, if yet to be defined, musical future.

Footnote:

Frank Auerbach died on 11 November 2024. David Sylvian shared these words on social media that day: ‘Very proud to have “collaborated” with Frank Auerbach back in the early ’80s when his work was in the process of becoming recognised for its mastery and his total commitment to the process of painting. At the time of his passing he unquestionably stands alongside the contemporary masters and those that came before.’

‘Oil on Canvas’

David Sylvian – all instruments

Music by David Sylvian

Produced by John Punter and Japan. From Oil on Canvas, Virgin, 1983

‘Oil on Canvas’ – official YouTube link. It is highly recommended to listen to this music via physical media or lossless digital file. If you are able to, please support the artists by purchasing rather than streaming music.

The featured image is Head of J.Y.M. II, 1980 by Frank Auerbach (oil on board, 26 x 24 in. (66 x 61 cm)) as featured on the cover of Oil on Canvas. William Feaver’s monograph on Frank Auerbach records that the painting is in a private collection.

Sources and acknowledgments for this article can be found here.

Download links: ‘Oil on Canvas’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Oil on Canvas (Amazon)

‘I never appreciated art to any great extent, I just saw it as paintings on a wall and I couldn’t open up. Then I saw the painting by Frank Auerbach (a twisting head like a granite fist in motion) that eventually appeared on the cover of Oil On Canvas and it just went straight to me. It was a shock because I’d never felt anything from a painting before and, since then, I’ve learned quickly, going from one painting to another, being able to experience something.’ David Sylvian (1984)

For me, this excellent piece of specialised journalism, touches upon a number of interesting facets of David Sylvian’s sensitivity, interests, work, life and taste and a few overlap with my own, music (always) and drawing (not so much now, but definitely in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80’s – I recall it started for me buying 1960’s Marvel Comics – very pop-art!)

Underneath the ‘Japan’ image – maybe David thought [their] music was more ‘the thing’ for European and Asian sensibilities, rather than an American ‘thing’? After all, in their respective early days, at least, T Rex, Roxy Music et al, weren’t ‘big’ in the States…Mott the Hoople and Jethro Tull were more initially successful, I think, from touring there (I also like both, particularly Mott).

The April 1982 image of DS in the USA – David looked confident and (for me) he was at or close to, the ‘top of his form’. After all, he was becoming successful in his work and young, why wouldn’t he appear so? He’d been thinking about music since the age of 12 and/or composition, we are informed.

Thanks to the VB for largely introducing me to Frank Auerbach’s work, I’d heard of him previously, but now in this context, I can appreciate the content and the skill, more. It was interesting that his son, Jake, was also ‘into’ David Sylvian/his work.

Yuka, London, 1983. polaroid montage supplemented by drawing (Sylvian) – I like this very much. A certain emotional intensity is perceptible to [this] viewer, maybe similar to the feeling David had when he looked at Auerbach’s work?…I was trying to achieve a similar thing in my spare time, but by the end of 1984, I didn’t think I was good enough to make a living out of such activity. I also like DS reference to being ‘hit…inside’.

‘Oil on Canvas’ sort of, x2. David was, it seems to me, inhabiting both worlds. Very enjoyable reading. Music, art, words, history and nature (links). All are important. Now I have to start redecorating the lounge…All the best…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing your response to the article, Jeremy.

LikeLike

Do you buy work yourself?

Whenever I can afford it. I’m not in a good enough financial position to collect regularly. I have an Auerbach – a chalk and charcoal drawing. He’s been a big influence on me. The work has a curious musical quality.

David Sylvian interviewed by Robin Dutt, Backchat, 1986

LikeLike