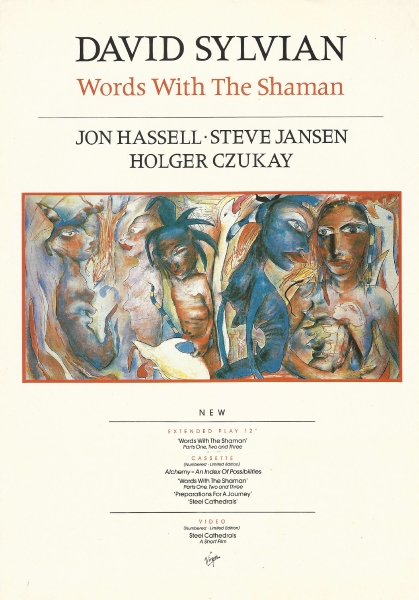

Words with the Shaman was released at the end of 1985, both as a standalone 12″ vinyl and as part of the limited-edition cassette, Alchemy – An Index of Possibilities. David Sylvian’s sleeve-note on the vinyl placed the recordings in context: ‘The compositions compiled for the E.P. were conceived as musical footnotes to some of the themes started earlier on the album Brilliant Trees, and were developed as a collaborative group effort for which I am very much indebted to all who took part.’

Credited boldly on the front sleeve were Jon Hassell, Holger Czukay and Steve Jansen, orientating us more precisely to side two of Brilliant Trees with its experimental compositions where Hassell’s distinctive timbres took us towards his ‘Fourth World’.

One name absent from the credits for Words with the Shaman, however, was the co-producer of Sylvian’s debut album, Steve Nye. Readers of this article will have most probably by now seen the studio footage from the Brilliant Trees sessions that was posted on the samadhisound vimeo channel in July 2021 (here). There we see Hassell, Sylvian and Nye together in the control room at Hansa in Berlin, experimenting with treatments of the American’s breathy trumpet-craft for the title track. There can be little doubt that Nye was a key contributor to the subtlety of the sound achieved on that record.

Replacing Nye for a co-production and lead engineering credit on the ‘footnote’ release to Brilliant Trees was Nigel Walker. Looking back, perhaps there had been a clue to this as a possible direction of travel. Whilst Walker did not participate in the studio sessions for Brilliant Trees, he was called upon late in the album’s production. ‘I had no input on the recording of that album,’ Nigel told me recently. ‘David did ask me if I would help him mix a couple of songs though – I have no idea why this happened, ask David I guess!’ ‘The Ink in the Well’ and ‘Backwaters’ have final mixes by Sylvian and Walker, whereas all the other tracks on Brilliant Trees were mixed by Nye. Walker was impressed with what he heard on the multi-tracks. ‘The recording was incredible,’ he remembers, ‘and between David and myself I think we did a good job on both songs.’

When Japan turned to Steve Nye to help oversee the sessions for their final studio album, Tin Drum, it was a move away from the production work of John Punter with whom they had forged a strong and trusted relationship, Punter having supported them in discovering their own distinctive identity for both Quiet Life and Gentlemen Take Polaroids. Nye’s skills were regarded as perfect for the next evolution.

Interesting then that for Words with the Shaman, Sylvian called in someone with a strong affiliation to John Punter and who had contributed to the more overtly pop sound of Japan that preceded Tin Drum. In fact, Nigel Walker’s first credit with the band was for their cover of Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ ‘I Second that Emotion’ which was released as a single in the wake of the Quiet Life album, record label and management no doubt concluding that a cover version would be more likely to provide the longed-for breakthrough with the record-buying public.

‘My work with Japan and with David Sylvian was always as an engineer,’ Nigel told me. ‘John Punter was the guy that got me into the music business and during my time as his assistant I would randomly throw ideas around. Not always great ideas, but sometimes someone without any real training will come up with something different.

‘Because John was producing and engineering his projects, he would let me record simple things as an engineer. It was really great to feel that he was watching me and guiding me through my early work.

‘The official way of recording at Air Studios was to get the best possible sound in the studio and then, using the best equipment, record the best possible sound onto the 16/24 track machine. Air had many great engineers who recorded that way. Maybe I was in the new revolution of young guns that couldn’t match the top Air engineers: we started to squash, destroy and paint the sounds in a different way – mainly due to our lack of experience.

‘John Punter liked to use phasers and flangers on his productions and when we got the Eventide harmonisers things started to get interesting… He asked me to help him on the ‘I Second that Emotion’ session.’

First impressions remain vivid in the memory: ‘Japan physically looked like they might be complicated or different than me but it took only an hour for us to kill that idea. Such nice people, funny and wanting to learn. I was named as the engineer but John was always keeping an eye on me. I liked the way Japan sounded at that moment. Clean but slightly electric and mysterious. It was only one song but I loved it.’

When Punter was asked to return to the production chair for Gentlemen Take Polaroids, Nigel Walker retained his place alongside him. ‘I guess it made sense for us to keep the same team for the album,’ he reflects. ‘We recorded in the same studio, same equipment and same result. Japan got better every time they came to the studio. They were different to all other groups at that time and the music business started to watch them closely.’

Then came the pivot. ‘Japan made the decision to change direction for the Tin Drum project. Steve Nye recorded in a different way to John Punter. I guess the group gave up any possible radio play and went for an organic, oriental, and more sophisticated sound with Steve, something that was his speciality… wonderful engineer.

‘I had nothing to do with that album but I mixed the live sound on the Visions of China tour promoting Tin Drum in the UK. That was great… that music sounded fantastic through thousands of watts of P.A..’

We may not have specific insight into why Sylvian invited Walker to work with him on the final mixes for ‘The Ink in the Well’ and ‘Backwaters’, but an explanation was given as to why the latter’s skills matched the assignment for Words with the Shaman, and it’s informative. ‘Because I wanted to give the music a hardness, a clarity,’ said Sylvian soon afterwards, ‘and I think that most people that work in that sphere of music tend to fall into it too naturally, they tend to think about it in a certain way, and I wanted somebody that thought about it as a piece of pop music, and therefore produced it in that way.’

‘Ancient Evening’ starts with a hum that summons a haze of heat rising from sun-drenched earth, and from the warmth of dusk emerges a crisply defined tribal rhythm. It’s an opening that demonstrates what Sylvian was seeking in turning to someone with a pop sensibility. ‘The drum sounds or whatever,’ he explained, ‘they are very bright, they are very sharp, clean, and that’s the way I wanted it to sound. Whereas if I’d gone to work with Steve Nye maybe it would have had the very warm feeling that he always uses, and it was something I wanted to get away from.’

Steve Jansen’s drumming is amongst my favourite of his work. The patterns are credible as indigenous beats, yet the intricacy of their architecture is unlike anything I’d heard before, constructed with a myriad of distinct strikes. ‘Steve Jansen’s drums were built up piece by piece,’ explained Sylvian, ‘they weren’t played as a whole – there was a bass drum, then a snare, then a hi-hat, and so on.’

Sylvian had worked previously with all the musicians except Percy Jones and was familiar with their recorded work. Czukay had been a favourite amongst the members of Japan going back to his album Movies, and Hassell and Jones were well known through their work with Brian Eno whose influence the members of Japan have acknowledged in many interviews. Sylvian went so far as to say, ‘Japan’s biggest influence, if you have to take an individual figure, was Brian Eno’ (1984). Indeed, Steve Jansen attributes Mick Karn’s move away from fretted bass to an Eno/Jones collaboration. ‘His inspiration to turn fretless I would suggest was upon hearing Percy Jones who played in BrandX…The Percy Jones performance that really did it was Brian Eno’s single b-side titled ‘RAF’.’ (2021)

Percy Jones may not have collaborated with Sylvian before this project, but he had appeared alongside Jansen on Ippu-Do’s album Night Mirage (1983) and the pair shared a stage for live shows with the band which were subsequently released as Live and Zen (1984).

The approach was therefore to give this trusted cohort plenty of freedom to express themselves. ‘It was a group effort ultimately,’ said Sylvian. ‘I’d sketched out the pieces beforehand and after I came back from doing ‘Steel Cathedrals’ in Tokyo, Words with the Shaman was recorded in London in 1985. I left things quite open in the studio as I always do when dealing with musicians of that calibre. I don’t try to pin things down too much, you know, but I edit a great deal afterwards and shift things around, especially with Holger’s input.’

Hassell’s trumpet rises from the vista traced in the opening bars. A delay effect returns a distant echo of every phrase, each one of which flows with a conversational quality, then flourishing into undulations akin to the sung entreaties of a human voice. The response when it comes is in the form of a ‘real’ person, no doubt from Holger Czukay’s carefully curated collection of found sounds.

Having not been in Berlin for Hassell and Czukay’s first meetings with Sylvian as they made their contributions to Brilliant Trees, this was Nigel Walker’s first experience of working with them. ‘I remember recording Jon Hassell. He used only the mouthpiece of his trumpet and made the notes by kind of singing into it… strange but magical. Holger and his dictaphone was also something I’d never seen before.’

‘When Holger came to London to work on …Shaman, he brought a handful of cassettes he’d taken from the radio,’ recalls Sylvian. ‘He’d suggest a cassette for what we were listening to, and say we’d leave the cassette running while we recorded. There are things that would fall into place, and anything that didn’t would be spooled back into the right place. I find that a very interesting way of working – leaving things to chance. That’s the way he works with the dictaphone as well.’

The technique tended to ‘spark off a whole set of ideas. We would then take off one sound, isolate it, and put it in different areas.’

‘I’m grateful for getting a co-production credit, although David was the real producer,’ reflects Walker. ‘I think as a piece of music it was something that neither of us had a clear idea of how it should be… or how long. I guess David had some moods, some feelings and emotions that he wanted to translate to music. We experimented all the time. I don’t remember exactly everything but we were a good couple of months working on it together.’

Sylvian told The Face that Words with the Shaman was originally one long piece but was cut into three because it had ‘begun to over-reach itself… it sounded too much of a grand statement.’ I had always accepted that Sylvian’s fascinations at the time meant that he set out from the start to create this work as an expression in instrumental form. But Nigel surprises me on this point. ‘Did you know there is a vocal part?’ he confides. ‘It didn’t make the final cut…

‘There were various parts with different instruments, recorded separately then joined together later.’

Sylvian recalled a case in point: ‘Percy Jones’ bass part was sampled bits of bass from what he had improvised over the track.’ Jones was living in the US at the time and says the experience ‘was a strange one because I got a call like on a Wednesday from someone at Virgin saying, “Can you come to London, do some recording with David Sylvian?” I said, “OK, when?” And she said, “Can you leave tonight?” So I grabbed a toothbrush and a bass and I flew over to London. I flew overnight and I thought I was going to be able to go to a hotel and sleep for a while. But a guy picked me up at Gatwick and took me straight to the studio – wasted, you know! So anyway I played and at the time I didn’t think I was tracking anything that was of much value to anybody.’ (2022)

Steve Jansen explained more about his work on the rhythms. ‘I remember it was an amalgamation of all kinds of percussion as well as a regular drum kit. It was recorded piecemeal which perhaps explains why the patterns sound less commonplace.’

One of the high points is the transition from the slow beat of ‘Ancient Evening’ into the irresistible exaltation of ‘Incantation’, the tempo heightened to a dance with the accompanying voices conveying abandonment to whatever ritual is taking place. ‘The main rhythm pattern from Part 1 and into Part 2 was played with fingers on a large drum, extremely close mic’d. In Part 2 the high end sounds are wire brushes on metal objects (probably Chinese cymbals stacked on the floor), and that’s a regular snare drum that has the snare (snap) off. Part 3 [‘Awakening’] incorporates log drums and cymbals. I don’t have a particular memory from recording those tracks except that I spent a lot of time exploring ideas on my knees!’ (2014)

Sylvian: ‘I was aiming for something between pop music and avant-garde music. My approach was to build up layers and layers of sound until something was working for me emotionally. I’m interested in unease in music, and instrumentals, if they are to work, must convey a sense of fascination. New Age music, to my mind, is a marketing term for record companies and an uncreative solution by musicians to the problems of making interesting instrumental music. On Alchemy… I allowed the players to do what they wished and shifted things around quite a bit in the studio at the editing stage so as to facilitate that.’ (1990)

Emotional connection was the heart of the matter for Sylvian. Indeed, it was how he defined the area of music he saw himself occupying. ‘If you think of the avant-garde as the bottom of the ladder and pop as the top, then I tend to work,’ [he laughs], ‘somewhere around the middle.

‘I don’t think I could work completely within the avant-garde because most of them are extremely proficient musicians and,’ [more laughter], ‘I’m not. Because I have no technique as a musician, I tend to rely totally on the emotional content. But both pop and the avant-garde tend to suffer from a lack of emotional content – that is fundamentally my biggest criticism.’

Nigel Walker: ‘Looking back on it, I like the fact that David Sylvian could make the music he wanted without anybody interfering with it. It was never going to be something commercial but it still sounds OK to me. Although my engineering of sound had improved a lot, my office work hadn’t yet reached its peak and I can hear the tape hiss throughout the final mix… nobody is perfect!’

Sylvian was candid in admitting that making Words with the Shaman was something of a struggle, which was in part created by the new set of circumstances he had contrived in which to work. ‘I’d co-produced Brilliant Trees with Steve Nye and also worked in that way on Japan’s albums. Working with Nigel was different because he was a younger engineer and I felt I could involve myself more technically in the work than I would as a rule. Normally my production credit relates to my role in the relationship between the musicians. I like to work with a producer who I have 100% trust in, who knows what I’m thinking and what I’m aiming towards, so that I can concentrate fully on the music. Making Words with the Shaman was a very hard slog, but rewarding. I’m very pleased with it and I think it’s the best thing I’ve ever done.’

Part of the issue was that whilst he admired Walker’s crafting of sound, the two were coming from different philosophical standpoints when it came to the spiritual concepts that underpinned his vision for the piece. (A companion article to this one, to be published shortly, will look more into the significance of the image of the shaman.)

‘I think for the most part, as long as you have a strong vision in your mind, you can carry it through regardless of the environment you are in. Working on …Shaman,’ he said of his co-producer, ‘I chose him on purpose. Because he had no interest in that kind of music. He prefers pop music and relates to that far more easily. As a character he doesn’t really understand anything of a spiritual nature, he has no interest in any form of religion or whatever, so I find it very interesting working in that situation. I managed to come up with something which for me is one of the most successful things that I’ve done…I think it’s possible to overcome a circumstance if you’ve got the presence of mind to see something through. I must admit it took me a long time to do it, that piece of music…’

Nigel Walker would work with David Sylvian again when he returned to live performance after the release of Secrets of the Beehive, his first shows as a solo artist. The In Praise of Shamans tour explicitly shared a theme with Words with the Shaman and the three instrumental movements of the release book-ended an ambitious performance.

‘The last time I worked with David was on his world tour in 1988,’ Walker recalls. ‘He had all the best guys in the band and me doing the sound. What could possibly go wrong?!’

Once again, it wasn’t all plain sailing. ‘There was very little budget left for sound. In the USA we did about a dozen shows. Every night I would be given whatever desk and speakers that the venue has. Sometimes good and sometimes… haha, it was tough. It was also suggested that I help to load and unload the musicians gear which wasn’t our original agreement…

‘I enjoyed the travelling and the two-hour shows were great but I wasn’t really the right kind of engineer to do all the other stuff, so after the Japanese leg of the tour we parted company. I worked with a new engineer for a couple of European shows, then I left. I did record a few shows in London, I think, although they are still sitting somewhere in a vault.’

Hearing the live reinterpretation of Words with the Shaman was one of the many highlights of the show for me, by then its every nuance burned in my consciousness through countless plays. Within the familiar structure there was again room for the chosen musicians to express themselves, particularly the band’s ‘soloists’ – David Torn on guitar and Mark Isham on trumpet. Something in that spontaneity caught, if only fleetingly, Sylvian’s vision of a show incorporating improvisation amidst the construct of the songs. This time, of course, there was no re-editing after the performance as had been the case for the studio creation. Maybe that rawness was why Sylvian backed off the originally planned official release of the show on record.

Words with the Shaman confused me when I first played the vinyl. My familiarity with Brilliant Trees did not prepare me for an instrumental appendix to those ideas. However, it soon became adored as every listen revealed new details. And there for me lies the fascination of this musical journey with David Sylvian, leading to sounds and places that I would in all likelihood never otherwise have encountered.

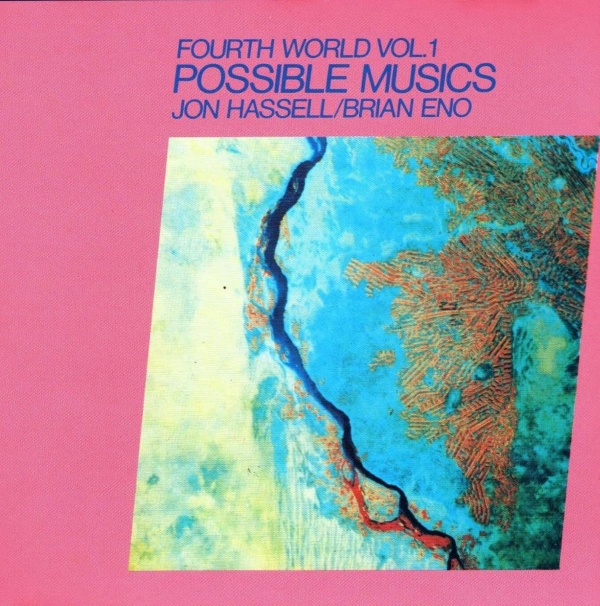

When the album Fourth World Vol. 1 – Possible Musics was released in 1980, Jon Hassell wrote an essay for the press release headed: ‘Some answers to the question: “What are some of the possible musics on this planet at this time?”’ He would later reflect that this ‘looks a little bit like the first “Fourth World” manifesto.’

Jon described his concept as follows: ‘“Fourth World”, that is, beyond “Third World” – a primitive/futuristic sound combining features of world ethnic styles with advanced electronic techniques. In its highest form the blend of influences creates an impression of a new, unified sound.’ Elsewhere he would describe the idea in mathematical terms: ‘the 1+3=4 formula…a symbol for an idealised interbreeding of “first” (technological) and “third” (traditional) world influences.’

By this time Hassell had spent time in India immersing himself in indigenous musical forms with Pran Nath (read more in ‘Brilliant Trees’) and had been struck by a major difference between music in what we sometimes describe as developed countries and that of the developing – or traditional – world. ‘Consider that in India, Africa and many other cultures (if any separation between classical and popular exists at all), classical music is sensuous, it’s built over highly-inflected (“jungle”) rhythms, improvisation plays a major role, expressing a mood is a primary goal and it communicates to all classes of people. The popular music often is similar but less rigorously formed.

‘In Western culture, no form in which improvisation is a major element is considered classical. Further, anything that is openly sensuous and/or uses certain rhythmic inflections or even certain instruments is automatically relegated to some “low” category (jazz, rock, mood music, etc.). This is the equivalent of etiquette rules: Do this, don’t do that – if you want to be visible as a member of a certain class.

‘Obviously, a kind of cultural racism is at work here which, more often than not, reduces non-European things to “curio” status. Any trend which softens this centuries-old superiority complex (hardening of the categories) should be welcomed.’

Hassell would invite Brian Eno to share a lead credit on the LP. ‘Eno was then living in New York and had picked up my Vernal Equinox record and – by his telling – had spent a lot of time that summer immersed in it, so he came up to me…introduced himself and suggested that we work together on something.’

‘There was always mutual learning going on between us, a healthy creative tension and ultimately, a place of congruence between his art school, non-musician approach and my musicianly, composer-virtuoso view (probably a somewhat defensive one, since I’d spent lots of years getting to where I was and just who was this “amateur” who couldn’t read music!).’

The opening track of the album, ‘Chemistry’, exudes the kind of energy that David Sylvian was seeking to tap into and develop further for Words with the Shaman. Co-written by Hassell and Eno, it’s an amalgam of their influences. Jon ‘called in the incomparable Nana [Vasconcelos] who turned me on to Ayibe Dieng, a terrific Senegalese drummer, and Brian brought in…Percy Jones, who did that great bass part on ‘Chemistry’.’

‘At that point I was living over here in New York,’ Percy remembers, ‘and I think Eno called me to go in and play. And I remember at first it didn’t seem to be going well. I was playing some stuff and Jon didn’t seem very happy with it and he was trying to explain to me what he wanted from the bass…so I’m thinking, this is not going to go very well. And then I heard Eno telling him, “Just let him play,” referring to me, “just let him play!” So, I did and it came out alright in the end.’ (2022)

Jones alternates between a five and a six-note figure with Hassell’s distinctive playing connecting with another world. ‘This was a time of trying to correlate the deep, traditional practice I had been following under Pran Nath along with my new “pop” associations and possibilities,’ Jon explained.

Even the sleeve demonstrated both the third and first world constituents of this “Fourth World”. Hassell closed his introductory essay: ‘Finally the cover art – a satellite photo of an area south of Khartoum (14º 16’ N ; 32º 28’ E) may be seen as a visual correlate of the musical thought: a “primitive” part of the Earth as seen from a space attitude.’

Words with the Shaman

‘Part 1 – Ancient Evening’ – ‘Part 2 – Incantation’

Holger Czukay – radio, dictaphone; Jon Hassell – trumpet; Steve Jansen – drums, percussion, additional keyboards; Percy Jones – fretless bass; David Sylvian – keyboards, guitars, tapes

Music by David Sylvian & Jon Hassell

Produced by David Sylvian and Nigel Walker, from Alchemy – An Index of Possibilities, Virgin, 1985

Recorded in London, 1985

‘Ancient Evening’ & ‘Incantation’ – official YouTube links. It is highly recommended to listen to this music via physical media or lossless digital file. If you are able to, please support the artists by purchasing rather than streaming music.

All David Sylvian quotes are from interviews in 1986/7, unless otherwise indicated. All quotes from Nigel Walker are from 2023. My thanks to Nigel for sharing his memories for this article. Full sources and acknowledgments can be found here.

Download links: ‘Ancient Evening’ (Apple); ‘Incantation’ (Apple); ‘Chemistry’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Alchemy (Amazon – vinyl re-issue); Fourth World Vol. 1 – Possible Musics (Amazon)

‘After Brilliant Trees I really wanted to further explore the relationship with Jon Hassell and Holger Czukay, developing themes which surfaced during the recording of the album as everything I do tends to contain the seeds for the next project.’ David Sylvian, 2001

More about Alchemy – An Index of Possibilities:

Awakening (Songs from the Tree Tops)

Preparations for a Journey

Steel Cathedrals

Articles about Brilliant Trees:

Pulling Punches

The Ink in the Well

Red Guitar

Brilliant Trees

Forbidden Colours (version)

Thank you David, another beautifully crafted piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating to read the background to this release. In my estimation, one of David’s finest pieces. I can still recall heading into Duckson and Pinker in Bath in the week before Christmas to buy the 12 inch on vinyl.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was always curious about the liner note that stated sound quality may suffer “due to the exceptional recording circumstances” or words implying something similar…. I assumed there were field recordings incorporated?

LikeLiked by 1 person

This comment relates to ‘Preparations for a Journey’ and ‘Steel Cathedrals’ which were developed from pieces created for the Japanese Preparations for a Journey documentary. The master tapes sent from Japan for the further sessions in London were marred by tape hiss, so a vinyl release of Alchemy was ruled out in favour of a limited edition cassette. The comment doesn’t refer to ‘Words with a Shaman’ which was recorded from scratch in London. More on ‘Preparations for a Journey’ here: https://sylvianvista.com/2020/10/23/preparations-for-a-journey/

LikeLike

thank you so much for documenting the sessions comprising my favorite Sylvian release. I recall buying the EP in Berkeley when it first was released, having eagerly anticipated it after enjoying Brilliant Trees so much – only to be disappointed with the excessively langorous tempo. Only after a few plays did I realize I should have set the record player at 45…I’d been listening to it at 33 rpm the whole time!

LikeLiked by 1 person