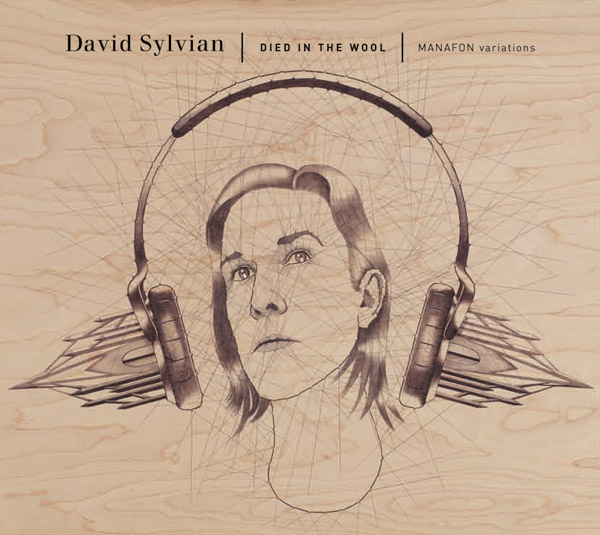

‘Died in the Wool came about in an incremental fashion,’ said David Sylvian of his 2011 double-cd set containing “variations” of tracks from 2009’s Manafon alongside a number of new pieces. ‘Wheels were unintentionally put into motion whilst I was still working on Manafon. I’d met Dai [Fujikura] in London, where he’d expressed a desire to work together. We’d continued an in-depth conversation via email regarding potential future projects. At some point it seemed like a good idea to test the water to see if we were speaking the same language.’

It was Fujikura who had sought out the opportunity to collaborate. In his book, Too Early for an Autobiography, he tells of an approach received from the Southbank Centre in London. The concept was to combine the work of a beat-boxing artist with a contemporary classical composer. Dai was doubtful. He was yet to co-compose with anybody, let alone someone from the beat-box world. However, Gillian Moore – Head of Contemporary Culture at the Southbank at the time – was enthusiastic and hers was an opinion that he valued, so Dai was persuaded to attend a performance by his potential partner in the venture.

‘Beat-boxing is a technique in which a person plays (sings?) a kind of rhythm machine with their mouth, making a drum-like sound to beat the rhythm, and then adding a bass-like sound in between,’ explained Fujikura. ‘I wasn’t interested at all. I found it boring and didn’t see any point in combining it with contemporary music…’

That night he emailed Gillian Moore to convey his feelings about the proposal adding, ‘even though I knew this was completely unrelated and off-topic, “If I were to explore the possibility of being involved with something like this, I’d like to collaborate with David Sylvian, who I’ve loved since I was a child, and I think that would be more interesting musically.”

‘I immediately received a reply from her. “Oh, David’s coming to a meeting about another project. If you like him that much, you should come too!”’ An hour-long meeting was planned and Dai was invited to join for the last twenty minutes.

‘I’ve loved David Sylvian since middle school,’ Dai writes. ‘After entering high school in England I bought everything I could find in small CD shops in rural towns. I must have had everything that was on regular release.

‘You can meet the person you admire! My heart pounded. It was February 2008. And the time has come. At the back of the Royal Festival Hall, in an ordinary café I’ve been to several times, David Sylvian and a few members of Gillian’s team are sitting around a table talking…Gillian introduced me to David and I spoke to him for the first time. Of course, I was moved and excited because I realised that his speaking voice was the same as his singing voice…David was a gentleman throughout. The twenty minutes passed quickly and I handed over both a CD-R which contained my music and my business card. I brought his album Blemish with me because I thought I might never see him again, so I got him to sign it. [Pierre] Boulez and Sylvian were the only two people I’d ever asked for an autograph, and that hasn’t changed to this day.’

Dai told David how much he knew and appreciated his music, ‘and at that moment I had the audacity to blurt out, “It would be a dream come true if we could make music together!”’

A few days later, Fujikura received an email from Sylvian. ‘I’ve returned safely to my home in America and am writing this while listening to your CD-R again…It’s really good. I would like you to participate in an album I’m making now.’ The sessions for what would become Manafon had completed the previous year and Sylvian was now in the process of assimilating the material.

‘I sent Dai a couple of tracks from Manafon for him to orchestrate,’ David recalled. ‘He’d already expressed a desire to re-work older material such as Blemish so I felt this might be the place to start.’ Fujikura: ‘David wanted me to listen to a few tracks from the album (there were tentative melodies but no vocals yet) and be free to write string parts that would go well with music. I received the tracks immediately and worked out some ideas.

‘After talking with him, we decided on a string quartet as the instrumentation…the question then turned to what kind of players to record with, and my first suggestion was the International Contemporary Ensemble, saying, “These are some amazing people!”’

The group’s website at the time stated their mission: ‘The International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) is a uniquely structured chamber music ensemble comprised of emerging performers and composers who are dedicated to advancing the music of our time. Through innovative programming, multimedia collaborations, commissions by young composers, and performances in non-traditional venues, ICE brings together new music and new audiences.’ There followed a number of endorsements, including from the New York Times: ‘In recent years the International Contemporary Ensemble has proved itself one of the most adventurous and accomplished groups in new music.’

‘The International Contemporary Ensemble was based in New York,’ says Dai. ‘David also lived a few hours’ drive from New York…The day before the recording, David and I arrived in Manhattan. It was the first time in New York for me. I stayed in the same hotel as David and I hung out with him from the afternoon until dinner. We had coffee at a café and went to an Indian restaurant in the evening. As a fan, I asked him a host of questions and heard various stories…Much of what he said was filled with respect for his past collaborators. I knew his albums so well that I recognised all the names that appeared in his stories.

‘After dinner, David and I took a walk through winter-time Manhattan, looking at the steam rising from the manholes, just as is seen in Woody Allen’s 1979 film Manhattan. Even if it was your first time visiting New York as a sight-seeing tourist, New York would have left an impression on you, but the feeling of spending half a day with an artist you’ve admired since childhood was nothing short of an exhilarating experience.’

Dai had worked with ICE previously and the sessions went well, the musicians working from his scores for pieces including the nascent ‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence’ destined for Manafon and an original composition that would subsequently be released on Sleepwalkers as ‘Five Lines’ (read more here). Sylvian and the recording engineer were delighted. Fujikura: ‘I was quite confident in what I had written. David was all smiles during the recording session and seemed very happy at the post-recording dinner. The next morning we ate waffles together at a diner near the hotel.’

Sylvian then took the material back to his home studio. ‘Although the sessions went well,’ he subsequently explained, ‘I later came to feel that the orchestration was working against the minimal aesthetic embraced by much of Manafon, and so discarded it.’ ‘One month later he told me the strings didn’t work, so he had to eliminate what I did,’ remembered Fujikura. ‘Now, I had never collaborated musically with anyone before, so this was a shock. Nobody has eliminated anything I’ve written.’

There was little alternative but to accept the position gracefully. ‘Of course, this is David’s decision. It was probably made as a result of a month of trial and error, in which he desperately tried to find ways to use my material as part of the tracks on the album. I was a little surprised and disappointed, but I guess that’s just how it was. After all, I had never worked with a non-classical artist and it was my first time participating in someone’s album.’

However, it seems that the idea of pursuing the material never quite left Fujikura’s mind. ‘A few months had passed, and I was still not sure how the parts didn’t work. I asked him, “Can I have a go?” He was so generous, he just gave me the whole ProTools sessions and I began to make remixes with my string parts. So basically I was just remixing for me, for my living room to hear, not to release any of these tracks.

‘I sent him the draft mixes, and he emailed me, “Well done, it works!” (In my heart I thought: “Of course they work! I wrote them to work!” [Laughs]). But I also think he thought the strings didn’t work for the overall feel of the Manafon album, but as a single track, they work.’ So much so that ‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence’ with the ICE string parts was included as a bonus track on the Japanese release of Manafon, credited as the Dai Fujikura remix.

Sylvian’s opening vocal, ‘Under yellow lights’, is entwined with serpentine coils of bowed strings in its reimagined setting. The original elements are not expunged, however. In particular, John Tilbury’s piano rings clear alongside deft plucks of acoustic guitar. The space that is a signature element of the original disc is retained, Sylvian’s voice alone in the pronouncement of:

‘No phone-ins, no courtesy

No kindness‘

‘Many people told me they liked my mix,’ said Fujikura, ‘and some said they wanted to hear the whole album with my mix. I passed that idea to David, and he liked it, so we started working on other tracks.’

‘I actually had no plan to work on a remix of the Manafon material,’ Sylvian clarified. ‘Some might be surprised to hear that I found Manafon a far more emotionally exhausting album to produce than Blemish. I didn’t have it in me to return to the material after completing it, plus I felt the work wouldn’t benefit from the same approach we’d taken on The Good Son vs The Only Daughter.

‘In the meantime Dai had asked to remix ‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence’ with his orchestration in the manner in which he originally intended it. Once finished, he expressed a desire to do more of the same. I could find no objection so, with Manafon complete, I sent the entire album to him as multitrack files. We set up a second session in New York City, again with the ICE ensemble, and covered a fair amount of the material from Manafon plus one original composition which was to become ‘The Last Days of December.’

‘As I said, it wasn’t my intention to create a remix album, and I’m not sure that’s what we have with Died in the Wool, at least not in the traditional sense. That’s why I went with the term “variations”, as these appeared to be extensions or variations on a theme… utterly sympathetic to the original material, but at the same time working against it, in the same manner that I was working against the original spirit of the improvisations which acted as body and catalyst for the creation of Manafon.’

It’s evident that for the second set of recordings with ICE, Fujikura is freed from the strict concept of complementing the work of the improvising musicians that had been relevant when Sylvian’s intention was to incorporate the string parts onto the Manafon album itself. In the case of ‘Small Metal Gods’, the opening track on Died in the Wool, the original instrumentation is entirely replaced by the string quartet arrangement. Only Jennifer Curtis on violin remains from the quartet line-up of the initial recordings which give rise to ‘Five Lines’ and Dai’s version of ‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence’, ICE being a flexible group of some thirty chamber musicians who came together in different constellations for each assignment.

Some felt that Fujikura’s versions made the material more easily digestible for the listener than might have been the case with the source material. Sylvian had this to say in the run up to the release: ‘Working with orchestration, fleshing out the melodic content inherent in the vocal lines, tends to make the compositions more accessible in that people appear to have a more immediate access to, and appreciation of, the melodies etc. Contrary to a number of commentaries on the original work, Manafon wasn’t a move away from the melodic; it’s just that the structures underpinning the melodies and the melodies themselves were more complex. These new arrangements might allow greater insight into that fact.

‘Dai is a fascinatingly original and protean composer, so whilst the work might ultimately be more accessible, it’ll lose none of its complexity, in fact it seems to take on a richer complexity but, to Dai’s credit, that doesn’t hinder the immediacy of the finished piece.’

Fujikura was clear that he wasn’t merely devising parts as an accompaniment to the vocal line. ‘Oh, I would never do that!’ he declared. ‘I want to disturb David’s voice (I am half joking). With love, of course!

‘Seriously though, I am not an orchestrator for him…in classical music, we don’t separate the vocal and instrumental parts of the music, so from my end, I never treated my work with David as just arranging a background sound/music. Definitely it wasn’t a side job for me.’

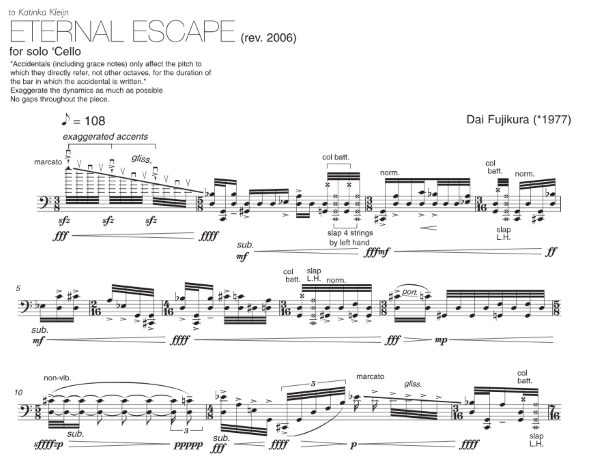

I enjoy listening to Fujikura’s contributions to Died in the Wool alongside selections from his own work. ‘Eternal Escape’ is one such piece, composed for solo cello. Katinka Kleijn, an ICE player with whom Dai worked before and during the Sylvian sessions, performed the premiere of this composition and has a version on her soundcloud account (linked below). ‘‘Eternal Escape’ is like watching a Scorsese movie,’ writes Fujikura on his website. ‘It should sound like (and be performed) with high energy throughout the piece with a lot of irregular rapid mood changes.’

Looking at the opening bars of the sheet music tells us much about the expressive nature of Dai’s composing. ‘Exaggerate the dynamics as much as possible,’ reads a note to the performer, alongside guidance that there should be ‘no gaps throughout the piece.’ The initial bar is a descending glissando that begins fortississimo (fff – extremely load) and rises to fortissississimo (ffff – as loud a possible), with sforzando accents – sudden with force. The time signature changes repeatedly and there are detailed notes for the use of extended playing techniques – ‘slap 4 strings by left hand’ and instructions to strike the strings with the bow as opposed to the conventional lateral bowing motion. The precision of the notation to achieve exactly the outcome desired is staggering.

The intersection of Dai’s practice with David’s could hardly be more stark. ‘For me the biggest challenge was how to let him “hear” the music I am writing for his tracks, because he doesn’t read music, so I can’t just pass on the score I write. Maybe this is normal in the pop world, but for me it was quite a challenge. There is no point in recording something totally unusable, because after all this is his album.

‘As a classical composer, one must write down everything before one hears a note, so I must know exactly what I might want in the session, before I hear a sound. David knows exactly what he doesn’t want when he hears it. It’s like an extreme filter, he knows very well what he doesn’t want for any given project. This is purely what I think when I am working with him (so he probably disagrees!).’

One of my favourite Fujikura pieces is ‘Fluid Calligraphy’ for solo violin from the album Ampere on Dai’s own Minabel label (2014). The liner notes tell us that ‘the composer purports to offer us an acoustic exploration of calligraphy, employing the violinist’s bow as if it were the calligrapher’s brush…The phrasing and accents don’t follow the arc of the melodic line, perhaps conveying the hesitant friction of brush against paper…’

Far from that first meeting on the Southbank being a ‘one-off’ encounter, as Dai had suspected might be the case, the two forged a firm friendship. ‘Since then, I’ve talked to David almost every day, sometimes three times a day, via email. David is a very studious person and always asks me questions like, “I want to know more about contemporary classical music.” Then he listens to the music I introduce and reads articles and books about it. A few years later [in October 2011], when David was in London, Boulez happened to be leading the Ensemble Intercontemporain in a concert at the Royal Festival Hall, and we went to hear it together.’

‘I didn’t expect it to be this close and “dramatic” a friend/working relationship!’ Dai shared when Died in the Wool was released. ‘I know that a lot of famous musicians talk about what close friends they are etc., but actually they aren’t. But between he and I (obviously I am not famous, but he is), we are very close friends. We have big arguments from time to time, but that is the proof of being close friends!’

‘Small Metal Gods – variation’

Erik Carlson – violin; Jennifer Curtis – violin; Margaret Dyer – viola, Chris Gross – cello; David Sylvian – vocal

Strings composed and conducted by Dai Fujikura

Strings recorded by Ted Young at Magic Shop Studios, NYC

Music by Werner Dafeldecker, Christian Fennesz, Michael Moser, Burkhard Stangl and David Sylvian. Lyrics by David Sylvian.

Mixed by David Sylvian & Dai Fujikura.

Produced by David Sylvian. From Died in the Wool, Samadhisound, 2011.

‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence – variation’

Werner Dafeldecker – acoustic bass; Christian Fennesz – laptop, guitar; Franz Hautzinger – trumpet; Michael Moser – cello; Keith Rowe – guitar; David Sylvian – vocals, keyboards, acoustic guitar; John Tilbury – piano; Jennifer Curtis – violin; Katinka Kleijn – cello; Wendy Richman – viola; Michi Wiancko – violin

Strings arranged and conducted by Dai Fujikura

Music by Werner Dafeldecker, Christian Fennesz, Michael Moser, Keith Rowe and David Sylvian. Lyrics by David Sylvian.

Mixed by Dai Fujikura.

Produced by David Sylvian. From Died in the Wool, Samadhisound, 2011. First released as a bonus track on the Japanese edition of Manafon, 2009.

All Dai Fujikura quotes are from interviews in 2011 or his book, Too Soon for an Autobiography (2022). David Sylvian quotes are from 2010/11. Full sources and acknowledgments can be found here.

The featured image is a photograph by David Sylvian from the galleries published at davidsylvian.com, ‘Dai ‘n ICE 2’, taken at the second sessions in New York for Died in the Wool at Magic Shop studio, Manhattan.

Dai Fujikura’s website contains a wealth of material about his work – daifujikura.com. Details of all releases on his Minabel label can be found at minabel.com.

Dai’s book, Too Soon for an Autobiography, published in Japanese, is available here.

Download links: ‘Small Metal Gods – variation’ (Apple); ‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence – variation’ (Apple); ‘Eternal Escape’ (soundcloud); ‘Fluid Calligraphy’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Died in the Wool (Amazon); Ampere (Minabel)

‘I had no intention of reworking Manafon. It’d taken its toll on me physically and psychologically and I was ready to be still … quiet for a time. It was Dai Fujikura’s interest in orchestrating the “songs” that got the project off of the ground.’ David Sylvian of Died in the Wool, 2011

More about Died in the Wool:

A Certain Slant of Light

When We Return You Won’t Recognise Us

Related:

A comment about the book cover. The Japanese title translates to ‘How did it come to this?’ 😎

LikeLiked by 1 person