An article was posted on Ryuichi Sakamoto’s official website under the heading: ‘Sakamoto has successfully ended his tour of the world.’ The text was a short message from the artist himself:

‘Our world tour which started in June has finally come to a close, ending in Osaka on September 1. Although only a week has passed since this last show, I am still feeling a bit burned out.

I would like to thank everyone who came to the shows. I look forward to the next time we meet on the stage and the Internet.

To those who love music.

love and peace,

Ryuichi Sakamoto

September 10, 1996’

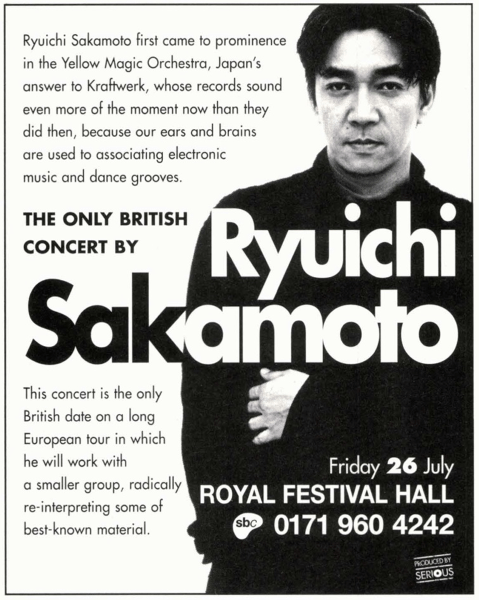

The trio world tour had begun that June with three consecutive nights at The Knitting Factory in New York, before moving to Europe for sixteen shows in the space of a month taking in Italy, Denmark, Greece, France, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland and the UK, darting back and forth across the Continent. The concerts presented Sakamoto’s instrumental music through a trio performance, Ryuichi on piano with cellist Jaques Morelenbaum and violinist Everton Nelson.

By now, Sakamoto was an established composer of film soundtracks and the set-list included stripped back versions of his themes for Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence (Everton tracing David Sylvian’s vocal line from ‘Forbidden Colours’ in the final section), The Sheltering Sky, The Last Emperor and more, interspersed among reinterpretations of material from across his catalogue, stretching back as far as Yellow Magic Orchestra’s ‘Tong Poo’.

I was privileged to attend the concert at London’s Royal Festival Hall, the last of the European leg. I remember being captivated by the intimacy of the performance, the sound so delicate you could you almost believe you were hearing the instruments without the benefit of a P.A.. It was a marked contrast to the Sweet Revenge show I had witnessed at the Hammersmith Odeon two years earlier, where an audience member had called out, ‘We want to hear YOU!’ to a bemused Ryuichi as he presented a hybrid of live band with video of the guest vocalists, including Holly Johnson for ‘Love & Hate’. Something had been lost in the precision of the technology, robbing the performance of some essential humanity.

Sakamoto’s online diary for the 1996 London trio show records his perspective on a busy and intense day:

‘At 3:30 a car comes to pick me up to take me to the Royal Festival Hall. We do soundcheck and the hall sounds good. My friends Yuka and Fumiya who live here in London show up to see me.

At 6 pm I go to the Museum of Moving Images which is located near the concert hall. There is a screening of Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence and Wuthering Heights. I go to participate in an informal interview with the audience at this screening.

At 7 pm I get back to the concert hall and get changed…

The 7:30 pm show begins. Many of those on our crew are from London and seem a bit nervous tonight. Even the musicians, including myself are a bit nervous about playing tonight. It’s because we are playing in London. The criticism and fame you get here can set the standards for you for the rest of the world. The audience in London are probably the most or the second most tough critics in the world. They all kind of sit back in their chairs and have these expressions on their faces that say, “show me what’s you’ve got.” I have had several shows here, but they were never totally rocking.

But things tonight were totally different. By our third song ‘Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence’ Jaques almost couldn’t finish his part because the applause of the audience was so great. We had four encores. I have never seen such a hot crowd in London as this evening… It was a perfect show, a perfect night.

I ask myself why is it that the trio ensemble is so popular with everybody? Why is it that when the material is more pop it doesn’t go over so well? Anyway, I know the answer. It’s because this trio format is more strong as music. The music is more direct and easier to understand for the public. Even the touch of my fingertips on the piano can be heard to the audience. There are no borders between the audience and us on stage to block the music…With this kind of music, the audience is able to get as absorbed by the music as the musicians.’

From London the performers flew to the other side of the world for shows in Australia, Singapore, China, Taiwan and Hong Kong. Then on to Japan for nine concerts to complete the outing, including three consecutive nights at Tokyo’s Bunkamura Orchard Hall – one of which was broadcast live on the internet as part of very early experiments with that medium – before two final dates in Osaka, finishing on 1 September. Perhaps when we attend just one date on such an extensive tour the incredible effort that is expended, both logistical and artistic, can escape us. Ryuichi wrote of the party on the eve of the last performance: ‘I go around and thank the entire production crew…Each one of them tells me a little story about all the hardships of this tour. Indeed, at every venue we had to face all sorts of obstacles…I think to myself one more time how the crew really performed so well under difficult circumstances. I realise how much I am indebted to these people. My head gets filled with memories of different scenes from the tour and I get teary-eyed.’

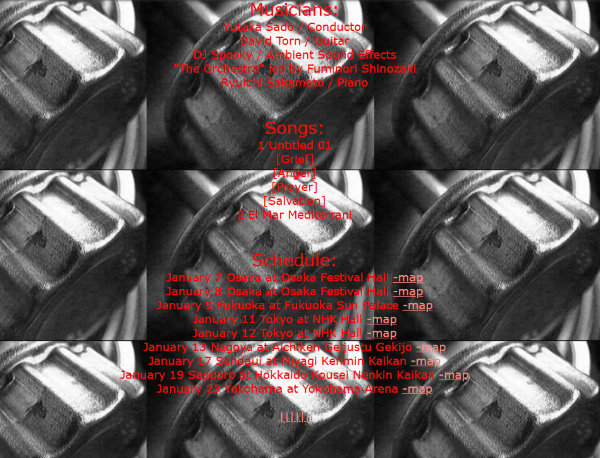

As one project came to an end, so Ryuichi’s next live excursion was already beckoning having been booked a year in advance. It would be an orchestral tour of Japan in January 1997 with rehearsals scheduled for the very beginning of that month. Three and half months from the date of his message marking the end of the trio tour might seem like ample opportunity to prepare, except for the fact that he was yet to write the new material required for the performance. By late November, Sakamoto was still short of repertoire to fulfil the commitment.

Writing new orchestral music was not unusual. However, in recent years this had been in the context of providing accompaniment for the movies he was scoring, both mood and context influenced by specific scenes and storyline and guided by the input of a director. Or, in the case of his work for the opening ceremony of the 1992 Olympics, there would have been a brief for the commission. For the upcoming tour, the new music would be entirely Ryuichi’s own expression. ‘I believe that concepts like…the philosophy of the music, the recipe with which it is made, only come after we get the music,’ said Sakamoto of his creative process. ‘In most of my cases it comes after the music is finished. When I write music I get a mood or an emotion or a feeling. I write and music leads me to some destination.

‘So I don’t know where I’m going until after I’ve finished the music. It’s a very unpredictable process. Music has its own language and grammar. When I’m writing I feel like I’m riding a wave or something. I’m just surfing it to see where I end up.’

The new work he composed for what would become the 1997 f tour of Japan was, however, by his own admission ‘different’. Whilst at home in New York during the preceding months, Ryuichi watched a TV documentary about the crisis in Rwanda and neighbouring countries. The Rwandan genocide had seen a reported 1 million people from the Tutsi ethnic group killed in a period of 100 days beginning in April 1994. Two years later, unrest spilled over into Zaire where many refugees had escaped and militia groups had become established. The result was more large-scale loss of human life and suffering, heightened because food was in short supply.

‘I felt a strong sense of indignation,’ said Sakamoto. ‘When I watched, I thought the crisis wasn’t just theirs, it was our crisis as well.’

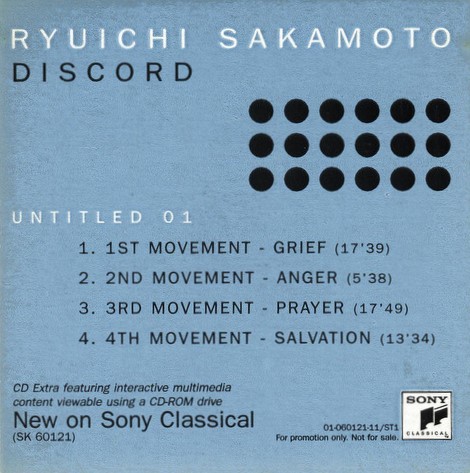

The orchestral piece that emerged was known as Untitled 01. A symphony in four movements: ‘Grief’, ‘Anger’, ‘Prayer’ and ‘Salvation’.

‘This time when I started writing I had clear emotions for each movement. So I was trying to realise these emotions in music. That was a very different writing style.

‘Normally I experiment with different things, unknown techniques, and I’ll use errors and accidents that happen when I’m writing. I sometimes do similar things to John Cage, putting patterns and ideas together randomly, without any musical consciousness. I may number some themes and then just throw some dice. You can get some weird, very unusual results, but it’s not always a success. But this time I started with the words, and then wrote as straightforward and quickly as I could because of my deadline in January…’

The first piece to be written was ‘Anger’, a visceral response to the scenes he had witnessed through the TV screen, bursting with rage borne out of the futility of war and a paralysing inability to positively influence the lot of those people impacted. It begins with colossal extended notes which release into an almost deranged cacophony of sound. When an assault of percussion comes to the fore it’s like the collective sound of the 70 players in Sakamoto’s concert orchestra thrashing around in utter despair. The movement is less than six minutes in duration but total exasperation is evident.

Part of the online content made available during the f tour, as Sakamoto continued to embrace the internet as a new channel for interaction with his audience, was a set of MIDI files of Sakamoto’s piano parts. One of these was his playing for the entirety of Untitled 01. Listening to the piano for ‘Anger’, which had been impossible to isolate amongst the tumult of the full orchestra and the additional performers on stage, it’s as if the composer is purging the raw emotion from body and soul.

Supplementing the full orchestra were two figures situated at the front of the stage, to either side of Sakamoto’s grand piano and the conductor’s podium. To the right was DJ Spooky at his turntables, and to the left was a familiar figure to followers of the music of the ex-members of Japan – David Torn with his Steinberger guitar, effects rack and keyboards.

The subsequently written first movement, ‘Grief’, is a much more reflective affair. The violin section’s emotive melody flows with empathy, the doleful tolling of a lone bell recalling those lost.

All four movements were ultimately completed over the course of a single month in December 1996. ‘I finished writing the very last note on the morning of the first rehearsal day. It was close! I didn’t have much time for experimenting,’ confessed Sakamoto. ‘The last two weeks I didn’t go out of my hotel room, literally. Just writing, notes, notes, notes…’

Just as he was an early adopter of online technology, so Ryuichi was utilising the latest technological tools to aid his composition. ‘I have a Macintosh with [Opcode] Studio Vision software and 16 tracks of [Digidesign] Pro Tools at home,’ he explained to Sound on Sound magazine. ‘My master keyboard was the Korg Trinity, which I like very much. When writing Untitled 01 I worked almost exclusively on the Trinity, saving everything I played in Studio Vision.

‘I improvised phrases and patterns and then it was a matter of going back and forth between the keyboard and the Mac, editing, changing, creating a shape and chord structure and so on. Once I’d developed a certain theme and decided that I was going to use it, I started improvising again for a theme for a ‘B’ section. Maybe it wouldn’t fit, in which case I discarded it and tried another idea. So I was composing the whole piece through from beginning to end. I wrote using the appropriate orchestral samples — strings, woodwinds, brass, piano, harp — and so ended up making a demo that sounded almost like a real orchestra…

‘What is very handy today is not only having the samples, but also the capacity to print out all parts from the sequencer. I did this at the end of my writing process, and then made final additions and changes on the actual manuscript. I think working with sequencers and samplers is a great way of writing for orchestra, but at the same time the modern process can make you lazier, especially from a rhythmic point of view.

‘Sequencers tend to be based around 4/4 metres and 8‑bar units. Even 5/4 is difficult to do. And if you think of someone like Stravinsky, who, especially in his ballet music, used irregular metres and structures all the time, that would have been very, very hard to do with sequencers.’

If the first two movements conveyed emotions stirred by the plight of those in Africa, then the final two articulated a different kind of response. ‘I tried to capture that state of being,’ said Sakamoto. ‘It’s a big challenge. Like for the last piece of Bertolucci’s Little Buddha (1994), I also had to write about an abstract state of being. In this case it was reincarnation, and I was struggling and suffering to do it.

‘The themes of ‘Prayer’ and ‘Salvation’ came out of the feelings of sadness and frustration that I expressed in the first two movements, about the fact that people are starving in the world, and we are not able to help them. People are dying, and yet the political and economical and historical situations are too complicated and inert for us to do much about it. So I got really angry with myself.

‘I asked myself what I could do, and since there’s not a lot I can do on the practical level, all that’s left for me is to pray. But it’s not enough just to pray; I also had to think about actually saving those people, so the last movement is called ‘Salvation’. That’s the journey of the piece.’

The sound of a single woodwind player opens ‘Prayer’, as if to emphasise that one person’s outpouring, ‘to anybody or anything you want to name,’ can be heard. Indeed, as others join in the theme, increasing strength is mustered. There is both serenity and resolve in the music.

For the final movement, Sakamoto asked various friends to reflect on what salvation means to them. First we hear Laurie Anderson, who declares that ‘salvation is an ongoing process,’ remembering her first response at a mission by evangelist Billy Graham at the age of 11. ‘I don’t know if you can appreciate now the charisma of Billy Graham,’ she recounts, ‘who just goes, “come to me, come to me, come to me…. stand up and come to me,”…And I still have the illusion that there is a guru somewhere. So I keep looking…… here is the last one…. THE ONE. This picture was taken at St. John the Divine…. you have here the bishop, he’s invited the Dalai Lama to come to St. John the Divine and talk, but also there were other people talking too. I was supposed to give a speech which was one of the worst moments in my life to give a speech in front of the Dalai Lama…Especially if you think that this is a person who is capable of a kind of very pure love, so if there is anything about pride or anything about your ego in what you are saying, it makes you feel very queasy…’ The impression of that talk given by the Dalai Lama ran deep, Anderson again recalling the event in an interview earlier this year: ‘He’s just one of the greatest speakers I’ve ever heard.’

The voice of DJ Spooky bemoans the negative impact of religious fervour in the world: ‘All the religions are saying, “salvation, salvation,” but they’re not doing anything to really try and change the mentality of the people that are at war or fighting. You know most major wars are fought for religious or ideological reasons, for salvation of one at the expense of another… these things probably need to change…’

Fellow performer David Torn expresses salvation as the outcome of positive actions by ordinary people. ‘Salvation in the Judeo-Christian sense is very distant and dream-like to me and, although it would be very nice if one day it came that way, I don’t count on it and I don’t act on it. I try to act what I believe should be salvation in my everyday life in my normal relationships with all the people that I meet.’

As the musical theme of ‘Grief’ is reprised, this time on flute, philosopher Kojin Karatani expresses his thoughts in Japanese. Then the music recedes briefly and all attention is drawn to the instantly recognisable voice of David Sylvian.

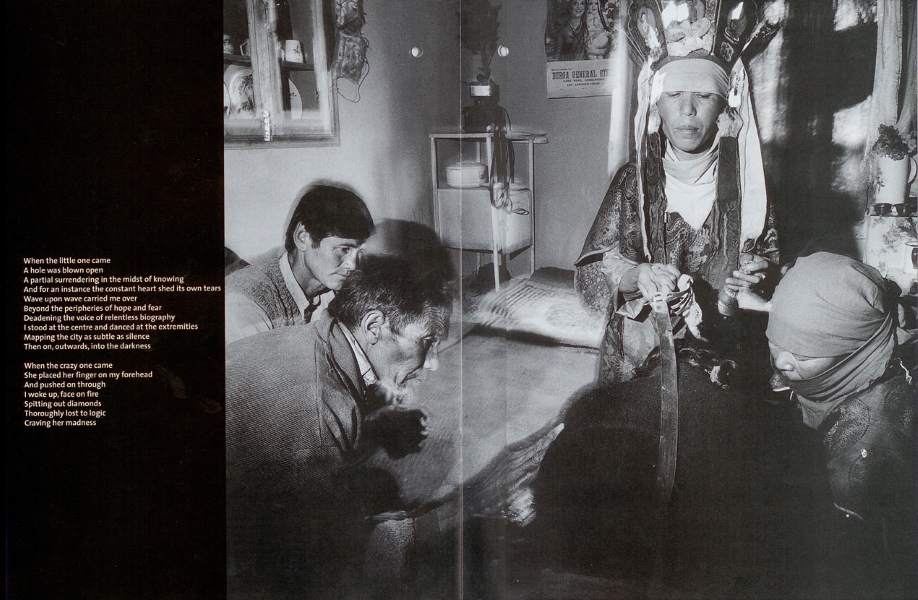

‘When the little one came

A hole was blown open

A partial surrendering in the midst of knowing

And for an instance the constant heart shed its own tears

Wave upon wave carried me over

Beyond the peripheries of hope and fear

Deadening the voice of relentless biography

I stood at the centre and danced at the extremities

Mapping the city as subtle as silence

Then on, outwards, into the darkness

When the crazy one came

She placed her finger on my forehead

And pushed on through

I woke up, face on fire

Spitting out diamonds

Thoroughly lost to logic

Craving her madness’

These mysterious words would later feature on Everything and Nothing with different musical backing as ‘Thoroughly Lost to Logic’. Before then, they were published in the February 1999 edition of Janus, a supplement magazine distributed alongside the Belgian newspaper De Standaard. For the article, A Shaman’s Song, Sylvian selected three of his own poems to accompany photographs by Carl De Keyzer from a series entitled, The Seven Oracles of Ladakh. These pictures follow ‘those specially gifted and respected men and women, “oracles”, who do healings, exorcisms and predictions under trance in the [North Indian] villages of Thiksey, Sabu, Choglamsar, Leh and Stok. These Buddhist rituals take place every morning in the oracles’ houses and are attended every day by about twenty people…Rituals last several hours.’

The photograph set beside Sylvian’s poem shows the oracle in shamanistic headdress, ringing a small bell whilst placing a ceremonial sword across the back of a kneeling supplicant as others look on.

This context seems to confirm Sylvian’s words as descriptors of revelatory experiences, dream encounters with those whose presence burnishes and whose wisdom goes beyond the sphere of human knowledge.

‘I believe that music can be very powerful,’ said Sakamoto, ‘and a part of me is afraid that music can be used in the wrong way. When you look at human history, music was sometimes used for wrong things — Nazis used powerful, emotional music to manipulate people, leading them in a wrong direction. So I want to be very careful with the power of music. As an artist I’ve always been afraid of that aspect of music, and yet on the other hand it’s also the beauty and attraction of music. So I have to be careful about achieving a good balance. I cannot drop the dangerous side of music, but I also have to get the right balance when I use it.’

Untitled 01, subsequently released on cd as Discord, was ‘very powerful,’ he said, ‘and I hope it will not lead people in the wrong direction. I want my music to be symbolic, metaphoric, without it having a straightforward message.’

There was no clear articulation as to how the salvation statements in the final movement were of direct relevance to those whose plight had so stirred the composer. Perhaps there was something about an answer lying beyond the level of human understanding, Sakamoto stating at the time that he was ‘not religious, but maybe spiritual.’ Perhaps the answer was in the practical expression of compassion for others, displacing dogma and transforming the world one heart at a time. Perhaps all this is for each listener to wrestle with for themselves, difficult questions being prompted by the work without tidy resolution. Discord in the world, and likewise in both the music and the mind.

‘We recorded all nine Japanese live shows, with a microphone for each pair of musicians. That’s almost 50 microphones, and that’s the reason why you can hear hiss at the beginning of the first movement,’ explained Sakamoto. Recordings were made both to a Sony digital multitrack recorder and on ADAT, and interestingly the latter was judged to be superior. ‘So we loaded the best performances from the ADATs into Pro Tools, and then edited them in there. Finally we mixed them… Both David Torn and DJ Spooky were mixed quite far in the background, because they were only playing atmospheric things; they didn’t play things that were part of the score. I played piano throughout. In sections of ‘Prayer’ I played inside the piano, directly on the strings. Incidentally, the percussion in ‘Anger’ was all played live; there were no sequencers used during the live recordings.’

Interaction was a key attribute of Ryuichi’s use of emerging technologies. Just as three concerts on the trio tour – from New York, London and Tokyo – were broadcast live on the internet, so was the final show of the f tour. On this occasion, an innovative ‘remote clapping’ facility was put in place so that the internet audience could show their appreciation and this could be relayed to the performers and live audience in the auditorium. ‘The system reflects the “remote-claps” from the network users to the big screen projected in the forms of the letters “f” with the minimum of delay,’ explained the official website. ‘Users can translate emotion by hitting the “f” key on the keyboard if they want to do so.’

Likewise, when Discord was released the following year, the cd had an interactive multimedia element allowing users to trigger visuals alongside the sound. ‘I always want to break down the walls between culture and technology,’ said Sakamoto.

And then there was further collaboration as the symphonic material was shared with musicians from other musical backgrounds who produced radical remixes that were subsequently released on separate discs by the Ninja Tune label. David Sylvian’s contribution, as far as I’ve been able to identify, features only on an edit of the 4th movement which appeared on the Prayer/Salvation cd.

‘Salvation’

Ryuichi Sakamoto – piano

The Orchestra led by Fuminori-Maro Shinozaki

Conducted by Yutaka Sado

Performed with David Torn and DJ Spooky

Music by Ryuichi Sakamoto

‘Thoroughly Lost to Logic’ © copyright David Sylvian

Produced by Ryuichi Sakamoto. From Discord, Sony Classical, 1998.

‘Salvation’ – official YouTube link. It is highly recommended to listen to this music via physical media or lossless digital file. If you are able to, please support the artists by purchasing rather than streaming music.

All quotes by Ryuichi Sakamoto are from interviews conducted in 1998 unless otherwise indicated. A key source for this article is Paul Tingen’s interview with Ryuichi for Sound on Sound magazine in April 1998. Full sources and acknowledgements for this article can be found here.

Download links: ‘Grief’ (Apple); ‘Anger’ (Apple); ‘Prayer’ (Apple); ‘Salvation’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Discord (Amazon)

‘I don’t want to contain straightforward messages in my music. Maybe because I was involved in political student movements (as a young man), and I was kind of disappointed after that. I want my music to be more metaphoric, symbolic. I’m pretty naive, pretty pure about music.’ Ryuichi Sakamoto, 1998

More about work with Sakamoto:

Bamboo Music

Forbidden Colours

Heartbeat (Tainai Kaiki II)

Zero Landmine

World Citizen – Chain Music

Concert for Japan

Life, Life

Until now it seemed very tricky for me to pidgeonhole ‘Discord’, especially after the heartbreaking elegance of the ‘1996’ treasure…

But once again, here comes the Sylvianvista breakthrough, the beacon, the enlightenment… and every tile goes exactly in place.

Thank you, David, both for your perpetual research and for your mastery in addressing “the permanence of memory”…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for taking the time to leave this feedback. It’s truly appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person