“The quality of art is that it makes people who are otherwise always looking outward, turn inward.” The Dalai Lama

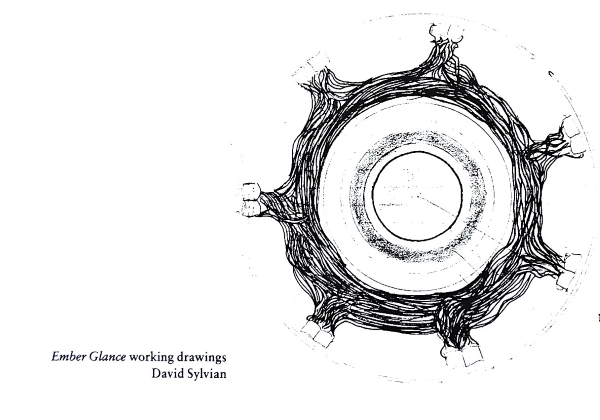

The above quotation headed David Sylvian’s artist ‘statement’ in the 1991 book of the Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory installation, the centrepiece of a boxed set commemorating the event held in Tokyo the previous year. Sylvian expanded upon the thought in his own reflections:

‘The road that leads to the development of higher levels of consciousness is reached, at least in part, through a process of self-questioning – the quality of these questions being in some ways more important than the answers. I believe that one of the main functions of art in society lies in its capacity to bring about subtle shifts of perception, possibly influencing the quality of the questions we ask as a result. The shift from conscious, outward projection, in which all events are viewed as external to the self, to a conscious, inwardly connected and more unified response is vitally important. It is through such a reorientation that real and sustainable change can begin to come about, in the individual and, consequently, in society.

‘These ideas have informed my work in music for a number of years now. My initial fascination with this project lay in the challenge involved in attempting to create, in three dimensions, a piece eloquent and potent enough to allow such an experience to take place.’ May 1991, London

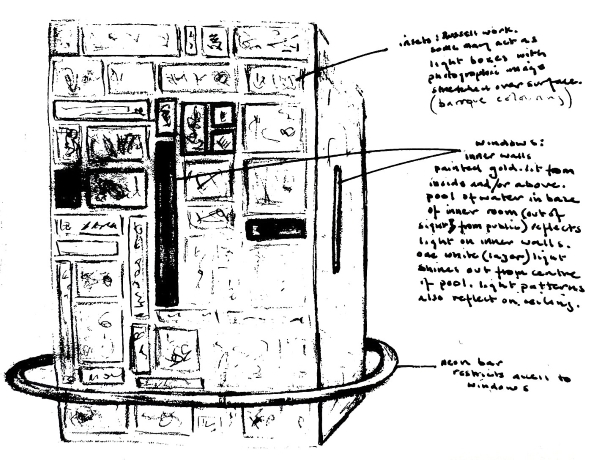

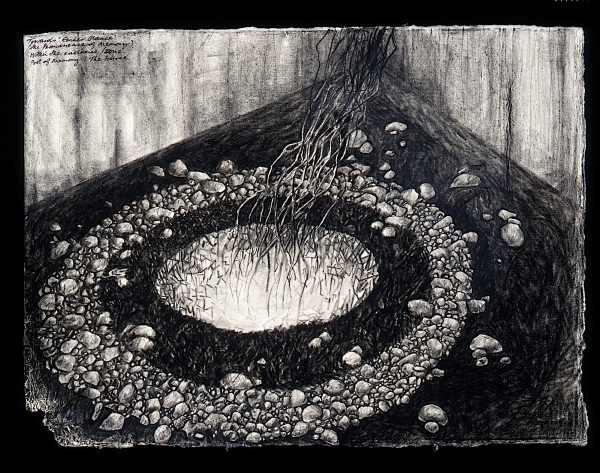

Rick Poyner’s essay later in the book, ‘Veils of Memory’, recalls the formative exchanges of ideas between David Sylvian and the artist Russell Mills. ‘The earliest proposals for Ember Glance,’ he writes, ‘were visual rather than musical. A sketch by Sylvian shows a raised pool surrounded by three circles, one of moss, one of bone and fossils, and one of twisted branches. Another shows a high-walled enclosure inset with boxes containing smaller works of art and pierced by vertical apertures intended to give glimpses of the pool inside. Both structures were rejected quite early on as being insufficiently layered or mysterious, though the motifs of the wall and pool remain at the core of the final design.’

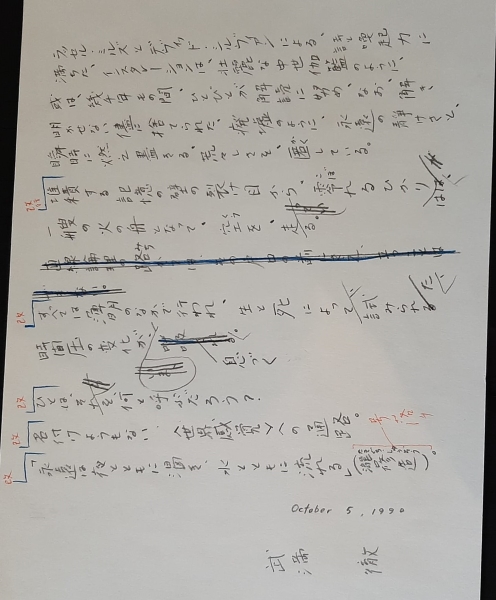

Sylvian’s handwritten notes give specific details of what the visitor should experience: ‘Windows: inner walls painted gold. Lit from inside and/or above. Pool of water in base of inner room (out of sight from public) reflects light on inner walls. One white (laser) light shines out from the centre pool. Light patterns also reflect on ceiling.’ Also: ‘Insets: Russell’s work. Some may act as light boxes with photographic image stretched over surface. (Baroque colouring).’

Russell Mills has previously shared with this blog the influences that, over preceding years, coalesced in his own thoughts and work and found articulation in the installation (see ‘Ember Glance’). What is clear both from the sketches and the scenes in the unofficial video documenting each stage of preparation is that Sylvian was immersed in the visual and conceptual design of the work alongside both Mills and fellow artist Ian Walton, the latter being responsible for the large wall – around a pool – that would be the ultimate manifestation of those early concepts. ‘We were given carte blanche to do whatever we wanted to do,’ Sylvian said. ‘So we come up with ideas that involved sculpture and photography and light and music.’

With the benefit of Rick Poyner’s essay and the extensive photographic documentation of the final work, we can undertake a virtual viewing of what visitors would have seen first-hand during the work’s public showing over thirty years ago:

Mills and Sylvian decided to use the idea of ‘layers’ and gradual disclosure to organise the spatial framework of Ember Glance.

Visitors were led through the darkened room of the Tokyo warehouse in which the installation was constructed by a series of diaphanous gauze veils. They did not know where they were heading, but they were drawn on by the blurred outline visible through the veils ahead.

Behind the first veil, suspended from a golden entrance arc, hung a mirror.

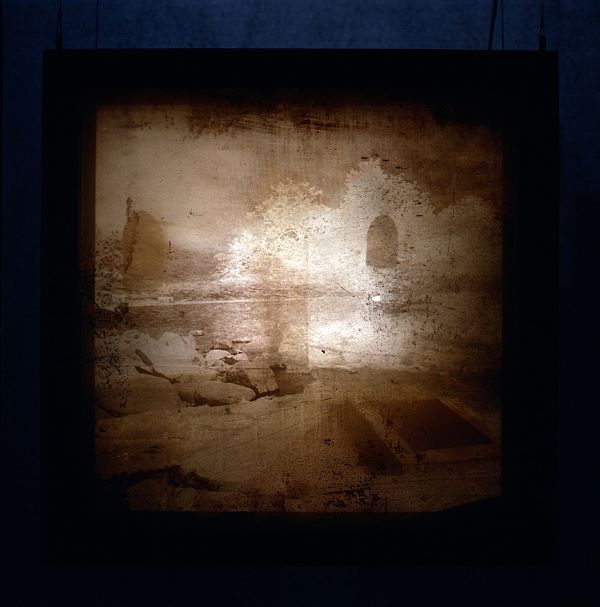

Behind the second were five lightboxes, spectral televisions constructed from old photographic plates, carrying images of landscapes and places; above each lightbox a speaker relayed a different sound.

Behind the third veil hung twenty-four wooden boxes filled by Mills with feathers, crosses, fragments of bone, honeycomb, the neck of a broken violin.

Behind the fourth floated a golden cloud woven from Russian vine.

At this point, looming in front of them, its top concealed in darkness, visitors encountered the curved wall of the enclosure, covered by a canvas thickly textured with paint by the British artist Ian Walton. At its base, a semicircle of earth was plated with burning candles. Rectangles of brilliant light – red, blue, yellow, green – emerged from narrow openings like the slits of a fortified tower…

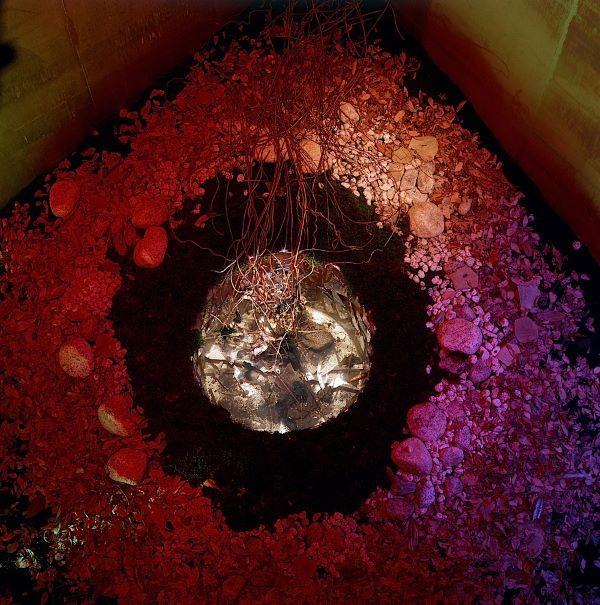

…through which it was possible to see the pool itself, a mysterious sunken vessel fringed with tendrils of vine and lined with shards of glinting mirror.

As the visitor peeled back the layers of Ember Glance, the environment underwent a continual process of change. Computer-controlled lighting filters gave colour an almost liquid fluidity. Sometimes the veils were transparent, at other times opaque. Lightboxes faded in, dissolved from colour to colour and faded to black according to their cycles. Sylvian and Frank Perry’s gongs, bells and ambient drones emanating from hidden speakers made time appear to slow, encouraging people to linger. Church bells, a keening woman, the clatter of a passing train and the distant sound of a barking dog mingled with the voices of Krishnamurti, Anselm Kiefer and Seamus Heaney.

In Ember Glance, Mills and Sylvian addressed the central importance of memory in our lives, using different kinds of recollection to structure the viewer’s experience of the event. Seen in this way, the mirror established the confrontation with the self that will be one theme of the installation.

The lightbox images that follow suggest conscious memories of the past, our sense of historical distance and the specificities of place…

…while the smaller boxes and their contents represent fragments of individual memories (in this case, Mills’ own), keys to trains of association and remembrance as charged and personal as Proust’s famous madeleine.

At the heart of the installation, largely concealed by the wall, is the ‘pool of memory’, the source, Mills suggests in one of his working notes, of unconscious collective memory and the buried ancestral origins of who we are. Zone by zone, the viewer has progressed from the domain of officially sanctioned public memory, through an exploration of his own private inner world, into a confrontation with a realm of memory that can be sensed, but which remains ultimately inaccessible and unknowable.

Whilst relishing the challenge of being fully engaged in the visual aspects of the project, Sylvian would later admit: ‘I am more eloquent as a musician than I am in other areas that I work in, and it’s more of a challenge for me to work in those other areas – to find my voice in those other areas, if you like. I tend to fall back on music more often because I can speak more fully.’ (1999)

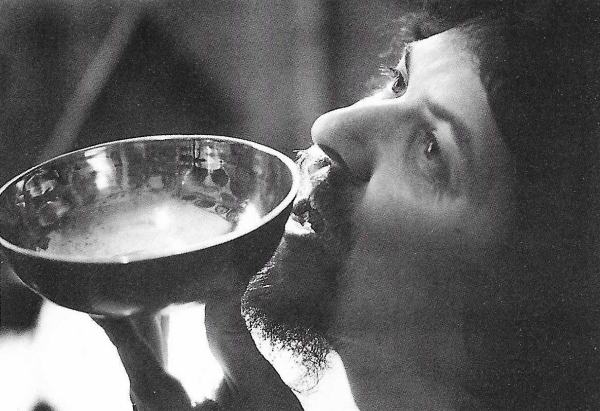

When it came to providing a musical environment to accompany the visual aspects of Ember Glance, it was Sylvian who addressed the challenge, inviting in Frank Perry to co-create the work. A 1986 profile of Perry described his craft as ‘coaxing ethereal sounds from ancient bells, cymbals, gongs, chimes and bowls. Frank Perry is not so much a musician – more an explorer…’ ‘I’m interested in communication,’ Perry is quoted, ‘and I believe that musical sounds affect people at very deep levels. I’m interested in providing a door or ladder into another world. I’m trying to materialise the spiritual.’

‘At the last count,’ the article says, ‘he had 52 antique Oriental instruments and around 100 from contemporary China or the East…Most fascinating of Frank’s strange music makers is his priceless collection of Tibetan singing bowls made from seven sacred metals and many centuries old. He strokes their rims with special wooden sticks evoking a shrill, clear note. He can change the pitch and “play” the bowl by raising it as it rings to his lips.’

The use of ancient instruments suited the themes of Ember Glance perfectly, their sound laden with the resonance of past generations, reminding us of how our own existence emerges from all that has gone before. Interviewed for Anthony Reynolds’ book Cries and Whispers, Perry indicated that his introduction to Sylvian came through Yuka Fujii. ‘She and David visited me at my home,’ he explained. ‘It was more of a business meeting really with David explaining why he’d thought of me getting involved (Yuka had played him my work Deep Peace to help him recover from maybe ‘flu), and he felt perhaps my sounds would fit in with his current project…a few days later I was recording at Metropolis.’ (2018)

The resulting long-form piece unfolds slowly. At times the chiming of bells and muted screaming of bowed gongs are in the foreground and then, in later passages reminiscent of his instrumental work with Holger Czukay, Sylvian’s atmospherics take over before the acoustic elements return. At around the 15-minute mark there is an orchestral crescendo sampled from György Ligeti’s Melodien. Listening to the music whilst viewing the photographs of the installation, one can imagine how its effect might have been to slow the mind of the visitor as they entered the darkened space, arresting time and heightening the senses to draw personal inferences from the visual stimuli.

The title of the piece is another reference to the recurring theme of bees in Sylvian’s work. Yuka Fujii’s book of ’80s photographs of Sylvian, Like Planets, carries the dedication ‘for the beekeeper’s apprentice’, undoubtedly a reference to Sylvian himself. In an accompanying statement Yuka wrote that the volume ‘documents a period in time, between the early to late 1980s, in which David changed, rather rapidly, from well documented glamorous pop star to retiring spiritual aspirant. He no longer wished to be in the distorting existential glare of the spotlight and consequently set out on a personal journey of the interior, in search of what he believed to be the source of creative life; being the light derived from within. He’d often refer to it as the inexhaustible well of inspiration.’ Sylvian has spoken of the beehive as ‘a metaphor throughout the ages for the structuring of society based on a hierarchy as led by its spiritual and philosophical masters’ (2010). The apprentice therefore seeking to assimilate the wisdom of those masters.

Divorced from the installation experience, perhaps it was challenging to engage with the music to the fullest extent. When the piece was re-released as part of the Approaching Silence cd in 1999, Sylvian was asked how he hoped people would listen. ‘I’ve lived with the piece Ember Glance [‘The Beekeeper’s Apprentice’] for almost ten years now, so I’ve heard it in a variety of different circumstances: obviously listening to it very closely when creating it, I’ve listened to it in the environment it was created for, which was a large space in Tokyo for the installation itself, and I’ve listened to it in the background. I’ve listened to it undertaking a variety of different activities and I’ve always felt it complementary to that variety of different circumstances. So, I’d encourage listeners to use it in a variety of different ways to see how they feel it would best service them really.’

Perry declared himself ‘somewhat dissatisfied’ with the end result. ‘All that Sylvian had told me was that the theme was to do with “memory”,’ he said. ‘I never did hear what little he had composed prior to the session but I was amazed that I’d recorded a whole album with so few of my instruments!’ The experience did, however, inspire him to create a piece of his own. ‘I wanted to explore in my own way what I could create using such a small number of instruments. So I chose to explore a simple meditative piece utilising the same mysterious sounds of eleven Indian “Noah Bells”, seven of which had been featured prominently on Sylvian’s piece.’ The result was 26 minute-long ‘Chintamani’ which was added as an additional track to the 1991 cd release of his album Crystal Peace (which I am yet to track to down for my collection). ‘It carries a very uniquely special and simple energy.’ (1999)

The Ember Glance book contains the following endorsement from legendary Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu:

This installation by Russell Mills and David Sylvian is filled with the power of poetry and evocation. Enclosed within it are both the stillness of eternity and the fury of instant conflagration. At one level, the installation is an imposing medieval cathedral; at another, it is a desolate, burnt-out ruin, abandoned by men who have failed to understand its ancient mysteries.

Light spills from cracks in the walls of layered memory and drifts through space like a flaming vessel.

The whole process takes place in near darkness. Life and death are transcended to animate the changes in the pressure of time.

What will people call it?

This nameless pathway that leads to a “world sensation”.

“Eternity evaporates like night’s dawning

It trickles away like water.”

Shuzo Takiguchi

‘In 1990, whilst collaborating with David Sylvian towards an installation, Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory, for F-GO SOKO in Tokyo, we discussed who might be appropriate to write an introduction to the book-cum-document of the installation. We immediately agreed on Takemitsu as being the right person,’ recalled Russell Mills in a 1998 feature on the composer’s influence in The Wire following his death in 1996.

Takemitsu’s artistic sensibility was most likely what drew them to him as the perfect fit for the installation. ‘His music is probably the only form of music that I see colours when I listen to it,’ recalled Sylvian in a radio documentary. ‘I mean it’s very visual. I know it’s visually inspired work because he was very inspired by what he saw, what he experienced. Obviously he talks extensively about Japanese formal gardens and he loved to talk about that in connection to his work. But also he was very much into visual art and I think that also inspired the works that he created in many ways and obviously cinema – cinema was incredibly important to him. And consequently his work has that visual component, I mean it draws pictures in the imagination, it kind of leads you through that ornamental garden, if you will. You know, he takes you by the hand and walks you through. It’s like going on a journey with a very dear friend, and it’s very impressionistic, you know, it really brings images to mind.’ (2007)

Who better then to introduce a physical journey through terrain that Sylvian, Mills and Walton had created. Sylvian and Takemitsu had already become friends after Sylvian incorporated a sample of the Japanese composer’s work into ‘Backwaters’ from Brilliant Trees.

Russell Mills: ‘We met him when we travelled to Tokyo to set up Ember Glance. Apart from discussing our installation and its intentions, we spent a great deal of time socialising with him, visiting splendid traditional restaurants where he, a tiny bird-like figure, would take control of the menu and order great numbers of individual “special” dishes, which to our palettes were mostly totally alien. Takemitsu would nibble at these now and then, preferring to absorb gallons of hot, then cold sake, alternating the two seamlessly.

‘Our conversations ranged as seamlessly as our drinking, floating from pop to the pollen loads of the honeybee, heavy metal to Haydn, matter to the “MA” (the Japanese philosophy of time and space), weather patterns to cybernetics. Our meetings were long, taking in several bars around the city, ending up in a small dark secret place high above the city lights, drinking until four or five in the mornings.’ (1998)

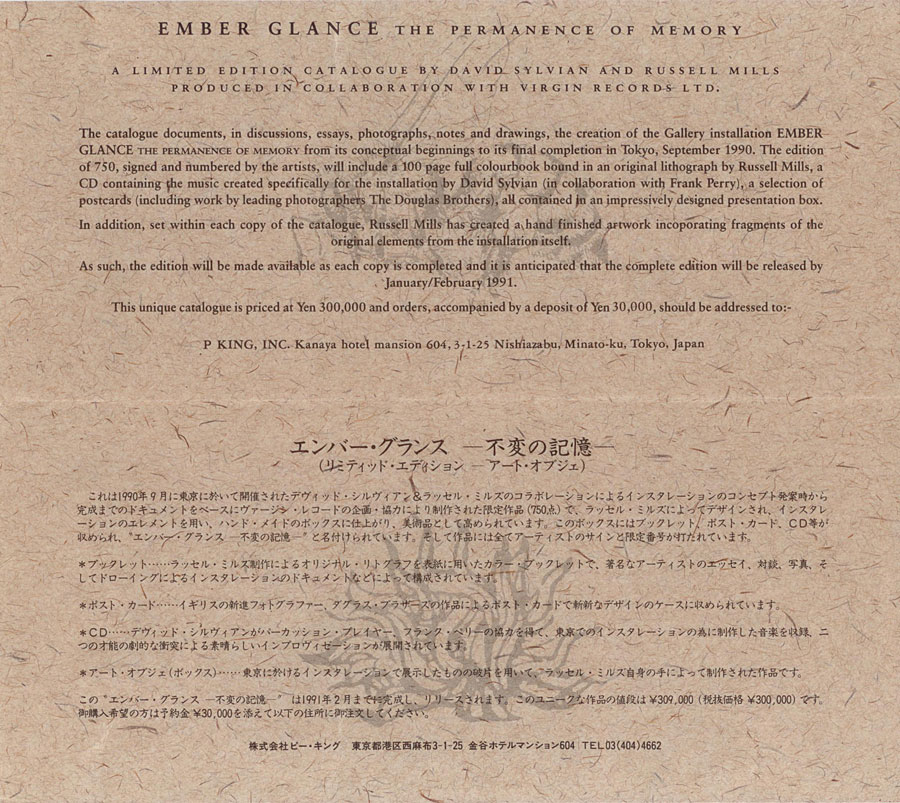

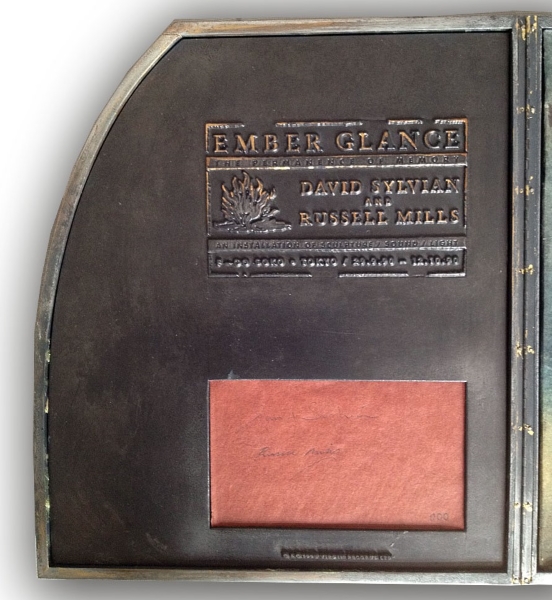

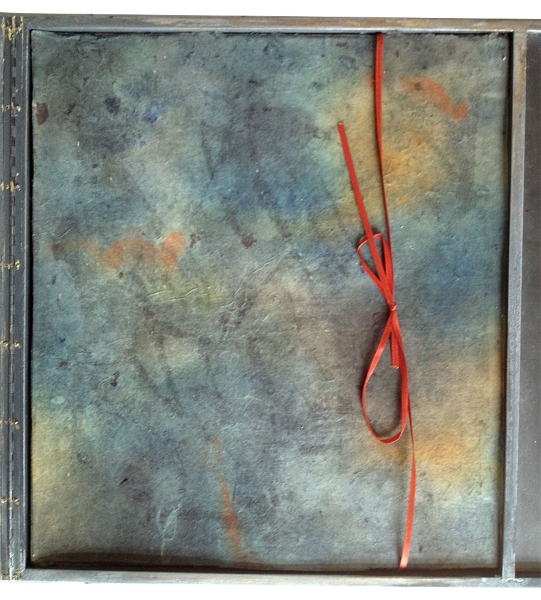

The Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory boxed set released by Virgin Records’ subsidiary label Venture in 1991, the year after the exhibition itself, is beautifully presented and a handsome record of the event. Sylvian: ‘Being site-specific, most of it was destroyed at the end of its duration, but it was well documented in photographs and drawings and so on, so we decided to put a book together with an accompanying CD documenting the whole event.’ Lavish as this was, the original intention had been even more ambitious. A flyer distributed at the installation promoted a limited-edition catalogue in a run of 750, signed and numbered by the artists. ‘In addition, set within each copy Russell Mills has created a hand-finished artwork incorporating elements from the installation itself. As such, the edition will be made available as each copy is completed…’ The price was 300,000 yen, which allowing for inflation is the equivalent of around £1,750 today.

A prototype was produced of what would have been an elaborate piece of art in its own right, signed by both artists in line with what was advertised. Now in the safe keeping of a collector, the box has two interlocking folding doors which open to reveal four internal sections. These include an embossed nameplate with details of the installation, a holder to accommodate the book, space for both the soundtrack cd and a set of postcards, and finally an assemblage containing ‘found’ items (a feather, two marbles, a fishing fly…) reminiscent of those incorporated within the 24 boxes from the exhibition itself. Sealed within this last section there is loose sand which shifts whenever the box is moved.

The costs of production of such an elaborate item were underestimated, as perhaps was the potential demand, and the deluxe edition was ultimately shelved. This aspect of the project over-reached itself and Sylvian, apt to look back on work with a critical eye, later questioned whether the installation itself had fallen into the same trap. ‘I found Ember Glance to be somewhat cluttered,’ he reflected in 1994. ‘I would’ve simplified it. I could have just worked with the final area… the partitioned wall. I think it would’ve been enough in that space.’

For my playlist I book-end ‘The Beekeeper’s Apprentice’ with tracks from Frank Perry’s most recent release at the time of Ember Glance. Zodiac (1989) contains a piece for each of the twelve astrological signs. The sleeve-notes give details of the instruments and techniques employed. ‘Taurus’ features ‘gentle striking of a symphonic gong…followed by the rich chordal sound of kei resting bells accentuated by high Tibetan cymbals. Finally, singing bowls which have not been made for 200 years are struck and their harmonic tones are accentuated by ululating – an ancient Tibetan technique in which the mouth cavity is used to vary the sound.’

‘Aquarius’ follows the piece recorded with Sylvian: ‘Rising and falling sequence of Chinese struck bells (Buddha gongs). Transition to faster seven-note melodies of medium-pitched Chinese and Japanese bell trees which increase in speed with varying rhythmic patterns. Deeper bells are introduced signalling the end of the sequence, which slows to a stop.’

‘The Beekeeper’s Apprentice’

Frank Perry – noan [noah] bells, bowed gong, finger bells; David Sylvian – guitars, synthesisers, shortwave, samples

Music by David Sylvian & Frank Perry

Produced by David Sylvian. From Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory, David Sylvian & Russell Mills, Venture, 1991.

‘The Beekeeper’s Apprentice’ – official YouTube link. It is highly recommended to listen to this music via physical media or lossless digital file. If you are able to, please support the artists by purchasing rather than streaming music.

Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory an installation of sculpture, sound and light by David Sylvian and Russell Mills. Staged at the Temporary Museum (F-GO SOKO: T33 Warehouse) on Tokyo Bay, Shinagawa, as part of a series of experimental exhibitions, installations and performances conceived and produced by national and international artists at the invitation of Tokyo Creative ’90.

29 September to 12 October 1990

Rick Poyner’s description of the installation and accompanying photographs were previously separately published on a supplementary page on this site. Photographs courtesy of Russell Mills. More can be seen at russellmills.com here.

The featured image is from the session in Sonoma, California by photographer Anton Corbijn in 1999, as featured on Approaching Silence which included the re-release of the music from Ember Glance, ‘The Beekeeper’s Apprentice’ and ‘Epiphany’. Copyright Anton Corbijn.

Many thanks to Sven Jacobs for the images of items from his private collection.

All David Sylvian quotes are from interviews in 1991/92 unless otherwise mentioned. Full sources and acknowledgements can be found here.

Download links: ‘The Beekeeper’s Apprentice’ (Apple); ‘Taurus’ (Apple); ‘Aquarius’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Approaching Silence (Amazon); Zodiac (Amazon)

‘The build-up to it [Ember Glance] was an incredibly intense period. For David, who was also going through some major personal sea-changes in his life, I guess it almost became an avenue of therapy which was brutally self-analytical. David recorded a beautiful sound-piece for it, which we later released. He was a very meticulous but simultaneously open artist, self-critical, capable of great humour and totally honest.’ Russell Mills, 1999

more about Ember Glance

A natural progression in time and (to me), the best follow-up article to last time’s ‘Oil On Canvas’. Only a true fan could juxtapose such writings (thanx VB) and referencing. David Sylvian was/is, inhabiting both worlds, as I had felt and thought, from multi-perspectives. Maybe too, the earlier articles ‘Ember Glance’ and ‘Epiphany’, were in my unconscious, at the time of my preceding comment, having commented on these too, back in 2020(?) A lot was happening for DS in 1991 (personally, Rain Tree Crow, fine art, the art/musical presentation…) David was about thirty three years of age and creatively firing on all cylinders. Sylvian and Mills are producing some deep and finely executed designs/objects.

The psychology of the changes in David Sylvian’s career seem to me, to converge here. The DL opening quote and from the middle of the third paragraph of this article, I think, confirm this. DS was freeing himself from the shackles of earlier influences, even if (I) really appreciate(d) some of those earlier influences, at least that is what has (to borrow from David) ‘…hit me inside’…from reading. All the best…

LikeLiked by 1 person