In the sumptuously presented book that came as part of the Ember Glance box set, before the reader sets eyes on anything of the installation itself, there is a section entitled ‘The Lakes: preparation’. Included here are treated photographs taken by The Douglas Brothers. A portrait of Ian Walton whose gloriously textural daubs of paint would grace the huge final wall in the finished display. Blurred frames of Sylvian in the Cumbrian outdoors. Hands sifting through rocks, twigs and bones, collating material to be incorporated in a public exhibition that will be staged over 5,000 miles away in Tokyo’s docks.

These photographs later came to life when a VHS cassette of the making of Ember Glance circulated amongst fans in the ’90s. The copy I obtained was of such poor picture quality that it was barely watchable, but here was two hours and fifteen minutes of behind-the-scenes footage documenting the preparatory stages of Mills and Sylvian’s elaborate artwork. The hand-held camera shots cover a period of sixteen weeks in the run up to the opening, encompassing concept, design, construction and finally display. I’ve never seen a clean copy of the film, but better versions than mine have surfaced online over the years.

‘The film was made by Yuka Fujii in Grizedale Forest in 1990,’ Russell Mills explains to me. ‘Ian Walton and his family had moved up to Ambleside in the Lake District, I think in 1989 or 1990, while I was still living in London. David, Yuka and I travelled up from London to spend a few days meeting him and to talk about ideas for Ember Glance.’

Mills, Sylvian and Walton are shown in a variety of settings during this visit to the Cumbrian fells. Walton was exhibiting at the time with fellow artist John Hodkinson in an upper room at John Ruskin’s former home, Brantwood, on the shore of lake Coniston. The trio are seen visiting the exhibition, Meta Incognita, musing over the artworks on display, and Sylvian even tries out the resident piano. (This is the same space that Mills would occupy for his solo installation Happenstance, twenty-nine years later in 2019).

‘I had been to the Lakes a few times as a child on holidays,’ Russell Mills remembers, ‘so I was already aware of its attractions, its beauty, and from my teens onwards I had become far more aware of its remarkable cultural history.’

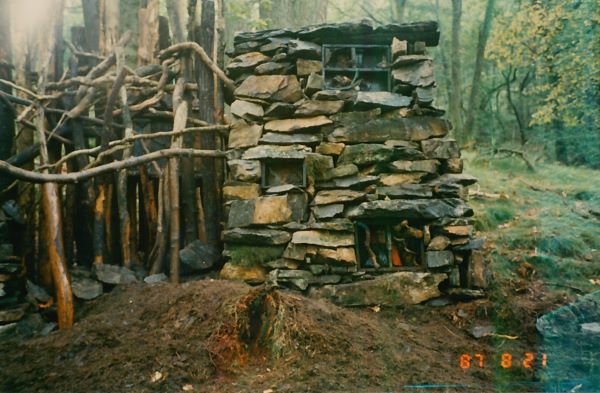

So what exactly were they doing as they sift through rubble in a Lake District pine forest? Russell took me back to another project to explain. ‘In 1987 I was commissioned by what was then Northern Arts (the regional Arts Council) to produce a piece in homage to Kurt Schwitters to mark the centenary of his birth. I invited my friend, artist and fellow Schwitters aficionado Ian Walton to work with me. After a couple of site visits to view possible locations and discuss the project with the then Director of Grizedale, Bill Grant, we came up and spent a few weeks making the piece…Following Schwitters’ lead and adhering to the ethos of Grizedale’s sculpture policy at the time, we used only found materials scoured from the forest. Nothing was imported from outside Grizedale.

‘With no set plan and working against time, the piece grew fairly organically. It ended up comprising two drystone walls either side of a tangle of vertical poles and branches. With foundations dug to about 2′ deep, the walls were built to about 7’ high and were about 3’ wide at the base tapering to about 1’ at the top. Within the wall and in amongst the vertical tangle we built in or inserted niches holding various found objects – reliquaries to Schwitters and the collage principle. Materials used included stone, wood and found objects such as old boxes, rusted metal and a split red rubber ball. Schwitters’ Elterwater Merz barn relief served as our influence and inspiration: the finding and inclusion of the red rubber ball being a fortuitous and direct nod to his relief. A family of mice took up residence soon after we’d completed it.’

The piece was christened ‘Shintin’, a name that was very agreeable to the Director, who had not been the easiest of partners in the commission. ‘He thought it sounded very Japanese, very Zen, and that it would probably help Grizedale draw more Japanese visitors, which meant more money. I didn’t contradict or correct him, but merely agreed that it sounded Japanese. I neglected to inform him that ‘Shintin’ is actually Yorkshire slang for ‘the lady’s not at home.’ I came up with the title for several reasons: I’m from Yorkshire; I wanted some gentle revenge for all his bureaucratic meddling and obstructive behaviour; I liked the sound of the word; and, importantly, I was sure Schwitters would’ve approved of the joke and its ambiguity.

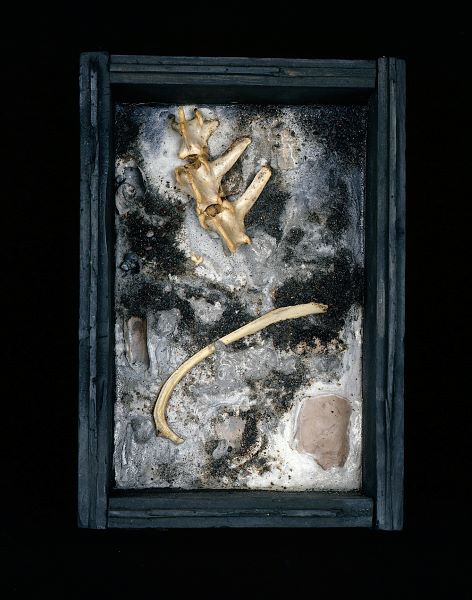

‘A few years after ‘Shintin’ was completed I heard from Grant’s former assistant that it was no more,’ the implication being that it had been deliberately destroyed. ‘Yuka’s film shows us sifting through the remains to try to retrieve various items, some of which I incorporated in the twenty-four assemblage boxes used in Ember Glance. Conversations between us led to ideas about the importance of memory, personal and collective, and its retrieval. Many of these ideas were the seeds for Ember Glance.’

Building this homage to Schwitters would have a significant impact on the lives of its creators. ‘Our time in the Lakes prompted both Ian and I to question why we were living in London…Ian and his family moved up a couple of years later and I and my family followed in 1992.’

It is certainly evident in the film that Mills it at ease in the great outdoors, as he explains to the bemused photographers what cuckoo spit is (insect larvae) and gives reassurance that it won’t cause any harm… Sylvian’s signature white shoes and, on this occasion, white slacks were not the most practical attire for the job at hand – but he participates with evident enthusiasm, and some classy publicity shots were obtained.

Mills and Sylvian are seen chatting through specific ideas for the installation as they examine the objects they find, during the return trip South by train and in later sequences shot in Mills’ studio. Here they share sketched concepts of how to present the work, and devise how best to integrate various objects and images.

‘Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory examines the ideas of space, time and memory,’ Russell wrote in the exhibition book. ‘We hoped, using sound, light and objects (found, made and manipulated) detached from their normal contexts and set in a theatrical space free of the usual associations, to suggest that memory in its richest sense should be central to our daily lives.’

The artworks were revealed in layers in a series of ‘zones’, with large gauze veils obscuring what laid ahead of the visitor and what was behind them as they progressed through the multi-sensory experience. A mirror was seen first, decorated with abstract patterns in which, it seems to me, can be identified various representations of the human face. The implication being that this is a space not only for each person to view the work of the artists, but also to reflect upon their own current reality and past memories. The Ember Glance book carries a quotation from the Dalai Lama, ‘The quality of art is that it makes people who are otherwise looking outward, turn inward.’

Mills continues, ‘Memory is triggered by small events, minute particulars rather than the general, the wonder of the commonplace rather than the epic. Our unconscious absorption of tiny fragments of stimuli – colours, sounds, smells, tactile impressions, atmospheres, snatches of conversation and half-glimpsed exchanges – feeds the imagination.’

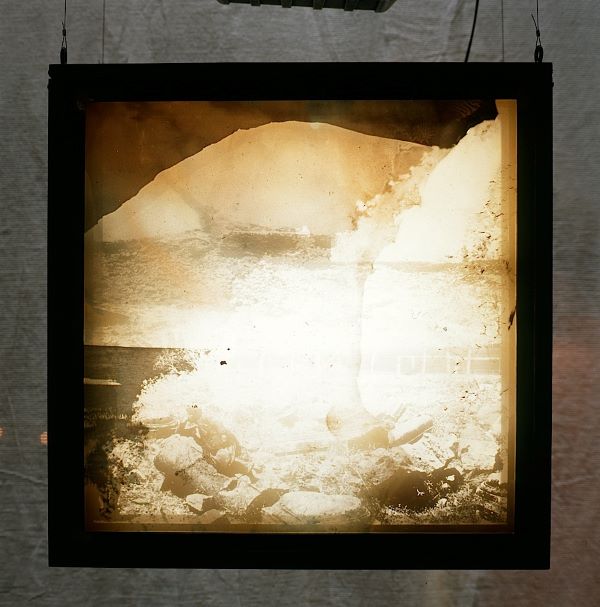

Collage then is an eloquent medium to convey such remembrances and to prompt connections for each one of us. After the mirror, visitors walked through a section of lightboxes which combined treated images like hazy scenes from the past overlaid on one another. Every box was themed: the mind, fire, water, air and earth, and each one was accompanied by a speaker conveying spoken word of significance (see ‘Epiphany‘). ‘The lightboxes carried layers of images from old plate negatives transferred onto film,’ Russell told me. ‘The subjects were shots of the Lake District by the Abrahams brothers and of Jerusalem and the Wailing Wall by we don’t know who. Ian had found these years before, the Abrahams negatives in some woods, but I can’t remember where, not in the Lakes, and the Jerusalem photos were, I think, found in a junk shop. Computer-controlled lights within the boxes were constantly changing in luminosity so that one’s focus was always shifting uncertainly between the two locations. Their use and marriage alluded to ideas of the importance of place, its symbolism, its pull (see Heaney, Kiefer and Beuys again).’

Next, a series of twenty-four boxes hung on invisible wire and containing fragments of significance – some garnered from the remains of ‘Shintin’ in Grizedale Forest. A frame of honeycomb from a beehive, metallic shards decaying into rust, a compass, fragments of bone, a deconstructed violin. Mills: ‘The mixed media boxes that I constructed were all semi-autobiographical assemblages, which dealt with various episodes from my life, along with references to some of my beliefs and preoccupations at the time’.

In closing his preface in the installation book, Russell says, ‘In memory, as in music, poetry and film, nothing is fixed. Time flows in any direction. Spatial and temporal times are fused: the past coexists with the present, the instant with the eternal, fantasy with reality. Memory knows no edges or boundaries, either physical or chronological. It provides continuity, giving shape to the known and substance to the speculative unknown. It is a filter for energies that connect us to our individual roots.’

Distilled in this representation of the nature and machinations of human memory is the influence of creative minds who have gone before, their insights an inspiration for new expression of eternal truths. ‘As with all the multimedia installations I’ve been involved with, every element is contextually anchored; all ideas and decisions come out of a great wide-ranging research, including into the history of the site and of events that occurred in them.’

Mills identifies a cultural revolution in the inter-war years that prompted a rejection of past structures as no longer adequate for unprecedented times; new idioms that can be found in works by James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot and Marcel Proust. Literary minds rejecting traditional narrative for more complex and less linear forms. Their methods had a parallel in the contemporary work of Kurt Schwitters, innovator in collage and pioneer of what we might now describe as multimedia installation. Russell points to 1922 as a pivotal year, incredibly seeing the publication by these authors of the masterworks Ulysses, The Waste Land, Jacob’s Room, and the first English language volume of In Search of Lost Time

‘It was in these works where I felt, and still believe, ideas of collage and contingency were first explored imaginatively,’ Mills expands. ‘Stream of consciousness, intimate musings and interior commentaries, asides, parody, appropriations, quotations, literary allusions, and free dream associations, were all used within formal and more amorphous structures to create fictional worlds made out of interweaving voices. Conventions of plot and character construction are abandoned. Neologisms and obscure English based mainly on complex multi-level word-play (sometimes recalling Lewis Carroll’s ‘Jabberwocky’) jolt and nudge into other readings. Short, juxtaposed phrases marked by internal rhymes and jagged syntactical breaks are used to suggest alternative interpretations. Virginia Woolf suggested that people are “mosaic” rather than monad, and Eliot wrote of his own voice being, “unlocatable, oddly outside and inside at the same time”, within a “Sunday park of contending orators.” Joyce, shortly after the publication of Ulysses, defending his preoccupation with Dublin, explained that, “If I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal.”

‘Woolf was influenced by Joyce, finding in his work a parallel striving to achieve what she too had been aspiring to. She described Joyce as “attempting to do away with the machinery” – the deadening conventions of what she called the “materialist” fiction found in a “first-class railway carriage” – and “extract the marrow.” She was also impressed by his manipulation of sight, sound, and sense, comparing his writing to a slow-motion film of a jumping horse, saying that “all pictures were a little made up before,” and that “here is thought made phonetic – taken to bits.”

The influence of these writers is evident not only in the artistic methods employed for Ember Glance, but also in the appreciation of the subject matter of our human cognitive powers and the nature of our recollections of the past. Mills picks up the thread, ‘In Modern Fiction, the revised version of Modern Novels in The Common Reader (1925), Woolf writes on Ulysses, “examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day” to examine how the myriad impressions that fall upon it “shape themselves into the life of Monday or Tuesday” with “no plot, no comedy, no tragedy, no love interest or catastrophe in the accepted style.” Prophetically, in 1919, in the original Modern Novels, when Ulysses was still a work in progress, she described it as discarding “most of the conventions which are commonly observed by other novelists. Let us record the atoms as they fall upon the mind in the order in which they fall, let us trace the pattern, however disconnected and incoherent in appearance, which each sight or incident scores upon the consciousness. Let us not take it for granted that life exists more in what is commonly thought big than in what is commonly thought small.”

‘In Eliot’s poetic counterpoint to Ulysses, The Waste Land, and in his subsequent works, ‘The Hollow Men’ and Four Quartets, there is a structural complexity in multiple voices in dialogue, with elisions in tone, location and chronology, and with themes overlapping and fragmentary. In Four Quartets’ first section, Burnt Norton, Eliot’s narrator contemplates the poet’s art of manipulating words as they relate to time, and to slippages in experiences, consciousness, and memory:

“Or say that the end precedes the beginning,

And the end and the beginning were always there

Before the beginning and after the end.

And all is always now. Words strain,

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,

Will not stay still.“

‘All these writers explore our receptive consciousness, exploring, in a world of overabundant auditory and visual impressions, the gap between preceding thought and what follows, the apparent lack of concordance between underlying trigger or intention and concluding utterance.

‘Another link I discovered in this expanding cat’s cradle of ideas and influences was that of Proust to Schwitters through the former’s discovery in Ruskin that the work of art can recapture the lost and thus save it from destruction, that art can triumph over the destructive forces of time. The idea of art being capable of transformative powers was central to Schwitters. While the Dadaists believed that art should be provocative, that it should challenge the bourgeoisie and attack the status quo, Schwitters believed that art should be transformative and could lead to change for the better.

How apt it was that Ember Glance should rise from the remains of ‘Shintin’, being a monument to his life, work and influence. ‘Apart from being seduced by the aesthetic beauty of Schwitters’ works, particularly his tiny, jewel-like collages, I was also interested in their semi-autobiographical nature in which elements that referenced current affairs were integrated into the works. Many of these works could be read as fragmentary diary entries, with allusions and sly asides to political events and social conditions next to bus tickets revealing routes, dates and fares. In his assemblage Merzpicture 29a (1920), for instance, he has incorporated a series of wheels that only turn clockwise, possibly alluding to the Germany’s general drift to the Right following the Spartacist Uprising of January that year. Even in his use of more commercial material, especially in his later collages that feature proto-pop mass media images, Schwitters’ was making critical comments about aspects of society that he believed were deleterious. En Morn (1947), made in the last year of his life in Ambleside, includes a magazine photo of a young blonde woman, which could be read as a warning against consumerism. These images directly influenced Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton in the UK and Robert Rauschenberg in the USA in the late 1950s, all of whom made works using mass-produced imagery to attack or satirise contemporary lifestyles and aspirations. From Schwitters Pop Art blossomed. Rauschenberg, after seeing an exhibition of Schwitters’ works at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York in 1959, said, “I felt he made it all just for me.”

‘So all these influences and ideas about collage and contingency, duration, and the potential metaphoric charge of objects and materials used in juxtaposition, were buzzing in my head at the time I was working on Ember Glance.

‘I don’t recall David mentioning him having read Joyce, Woolf, Eliot or Proust. He may well have done, but whether he had or not didn’t really matter, as it was evident from our conversations that he understood the territory that was inspiring my thinking.’

It was Sylvian who contributed the second phrase of installation’s name. ‘The Permanence of Memory, as far as I can recall, was a subtitle that David felt was necessary. I understood its meaning, but thought it should have been presented as a query, with a question mark, as I’ve always considered memory to be mutable, inconsistent, prone to multifarious contingent forces, and therefore unreliable, rather than permanent. Our memories get jumbled, sometimes lost and then regained, they fade and reappear, get shuffled. We dig them up selectively, consciously and unconsciously, depending on our constantly changing circumstances. While memory is essential for our growth, in that it allows us to learn from the past, perhaps paradoxically, I think its real importance is to be found in its unreliability and its impermanence.’

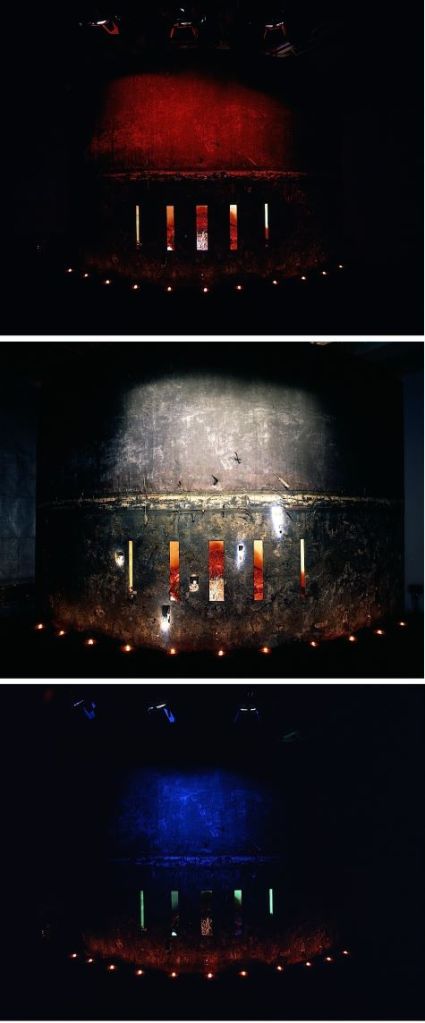

These concepts of the workings of our individual minds directly influenced the sensory experience that Mills and Sylvian strove to present in Tokyo. ‘In an attempt to mirror nature’s processes and the contingent flux of our daily lives, every aspect of Ember Glance was devised to be constantly changing. Lighting was programmed to run on extremely long varying cycles of very slow change, from low to full luminosity, back to low to full, with the colours of each of the hundreds of lights also changing imperceptibly. Sounds were similarly programmed so as to switch between all outputs, with tracks emerging from different sets of speakers so as to be continually moving in air across the vast spaces of the former bonded warehouse. With the cycles of change being of varying durations, all events unfolded randomly, with unexpected and unimagined collisions and collusions happening throughout.

‘Visitors’ perceptions of the static elements were deliberately, but gently, disturbed by these sonic and lighting changes. Between each “zone” of the installation were huge veils of theatrical gauze, constructed in such a way as to react to changes in lighting: having appeared opaque, they would, as the lighting imperceptibly changed, become transparent. Shadows cast by the veils and suspended sculptural objects moved throughout, mingling with shadows from adjacent zones. Every aspect of the installation was changing in real time, but at a glacial pace.

‘Every visitor experienced the installation uniquely, depending on their position within it and its changing states at different times throughout each day. All the technology was left running every night throughout the installation’s duration so that the randomness continued uninterrupted. In both its content and its operations it attempted to emulate the processes of contingency in our daily lives and in the natural world’s ceaseless flux through the use of necessarily prepared chance. It also paralleled how memory works as a transient, shifting thing.’

The final zone of Ember Glance was Ian Walton’s giant wall, crafted in the Lake District and erected in the warehouse where slits were cut in its vast canvas to allow viewers a glimpse of what was within. Above them was suspended a cloud made of vine as they peered in to catch sight of a pool, representative of the source of the collective consciousness and history that we all share but which is beyond the experience of any one of us. The well-spring of life, common to all but ultimately unknowable.

‘The cloud of vine hanging in front of the wall referenced ideas from The Cloud of Unknowing, as well as suggesting ideas about interconnectedness, our “tangled web”, adaptability, fortitude, the drive to survive, etc.,’ Mills explains. ‘The pool within the wall was meant to suggest collective memory, of a family, a village or town, or a whole nation.’

In a Japanese TV interview coinciding with the exhibition, Sylvian said, ‘It’s really for the individual to make of it what they will. We’ve obviously tried to incorporate as many triggers in the installation as we possibly could.’ Art as catalyst for a moment of revelation. As Mills describes it, ‘Like gazing into a dying fire and our attention being caught by a glowing ember threatening to spark into flame; we are suddenly jolted out of our mindless state to catch, perhaps, a brief moment of recognition of something significant that was previously elusive.’

Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory

an installation of sculpture, sound and light by David Sylvian and Russell Mills

Staged at the Temporary Museum (F-GO SOKO: T33 Warehouse) on Tokyo Bay, Shinagawa, as part of a series of experimental exhibitions, installations and performances conceived and produced by national and international artists at the invitation of Tokyo Creative ’90

29 September to 12 October 1990

Thank you to Russell Mills for his generous enthusiasm for our conversation and for permission to use photographs of his work. Full sources and acknowledgements for this article can be found here.

This is the second of two articles, read ‘Epiphany’ here.

A description of the Ember Glance installation with a gallery of supporting images can be viewed here.

The featured image comprises details from the exhibition book included in Venture’s 1991 boxed set, photography by The Douglas Brothers.

‘Memory is very like the wind. You can see the effect of the wind around you. You can see the effect of it, but you can’t actually see it. Man has very little control over things like the wind. And memory is the same, it’s just something that we have but most of the time we don’t really tap for energy. We don’t really consider memory – collectively or individually – as something that is important, because we are too busy getting through the days.’ Russell Mills, 1990

Excellent and insightful piece once again and great shots.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Paula.

LikeLike

Great article! Love reading Russell’s comments and thoughts about the installation. Having discussed with him via email his approach to art I remain amazed and in awe of a mind that is so different to my own!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Everything that I liked;

The depth of your writing. Fond memories. Trips of my own to the Lakes (with friends or family). The evident happiness of Sylvian et al, in the photographs. The aesthetic of the Shintin (1987) and the slightly misty morning back-light. The fact that a family of mice adopted it, as home. The return to the London studio. The Dalai Lama quote. ‘Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory’ (the overlaid photographic images, like a condensed ‘dream work’ – the one I recall from early this morning). The assemblage box ‘containing paper scraps and oddments’, revives further memories of my own, first looking at early 20th Century art collages. The indirect references (for me, not necessarily anyone else) to Ferry’s musical composition ‘Waste Land’ (I am aware of his liking of Eliot) and the pop art of the late Richard Hamilton (one of Britain’s founding pop-artists and Ferry’s tutor at Newcastle). Simply, an enjoyable read. Thank you Vistablogger.

Jeremy

LikeLiked by 1 person