‘New means change the method; new methods change the experience, and new experiences change man. Whenever we hear sounds we are changed: we are no longer the same after hearing certain sounds, and this is the more the case when we hear organised sounds, sounds organised by another human being: music.’ So said the ground-breaking composer of electronic music, Karlheinz Stockhausen, during a lecture given in London in 1971.

‘Until around 1950 the idea of music as sound was largely ignored,’ he continued. ‘That composing with sounds could also involve the composition of sounds themselves, was no longer self-evident…I was certainly a child of the first half of the century, continuing and expanding what the composers of the first half had prepared. It took a little leap forward to reach the idea of composing, or synthesising, the individual sound…I became very interested in the differences between sounds: what is the difference between a piano sound and a vowel aaah and the sound of the wind – shhh or whsss. It was after analysing a lot of sounds that this second thought came up (it was always implied): if I can analyse sounds which exist already and I have recorded, why can I not try to synthesise sounds in order to find new sounds, if possible…I began, as many others were doing in the musique concrète studios, to transform recorded sounds with electric devices.’

A decade later, the influence of this pioneer and his ideas was inspiring two young musicians as they created a truly unique sound environment for a track on their forthcoming album. ‘We took such care over each individual sound that we got quite paranoid about all sounds being new and different,’ said Richard Barbieri of his work with David Sylvian programming synths for Tin Drum. ‘My big influence on that album was Stockhausen, especially the abstract electronic things he was doing in the late ’50s. Listen to a track like ‘Ghosts’, for example, and you’ll hear all these metal-like sounds that hardly have a pitch, yet subconsciously suggest a melody.’

In fact, Stockhausen’s ideas on the construction of sound found a parallel in how Barbieri discovered his own musical voice. ‘I didn’t have any technical ability, and I didn’t have any musical theory knowledge,’ Barbieri recalls. ‘Until I got a synthesiser and then the controls became more important to me than the keys. I actually started to forget about the keys and just explored sounds using the controls. I found a way to do something that sounded different and that a standard keyboard player just wouldn’t go and play. That for me was the breakthrough – it meant my contributions to Japan were much bigger.’

Richard’s equipment demanded that he innovate with sound. ‘My first synthesiser was actually the [Roland] System 700 Lab Series, which is kind of a companion module to the big system. I think they used it in universities to teach people so it had aspects of all the parts of the 700. It was hard-wired but it was semi-modular as well, so you could use the patch plays and it basically didn’t make a sound unless you did something to it to make a sound. So that really gave me a good education and it got me into programming because nowadays you have a thousand patches on every keyboard with every sound you could think of, but in those days you had to create it yourself, so that’s where I had some talent, because I didn’t have the talent in the playing department. It made me understand about how synthesis works.’

Asked in a magazine Q&A ‘which record says the most to you about music technology?’ Richard’s response was: ‘Kontakte by Karlheinz Stockhausen, recorded around 1958/59,’ emphasising that it had ‘a very big influence on me’. It’s a composition that exists in two forms: the first for electronic sounds alone, and another for electronic sounds, piano, and percussion.

During the course of that London lecture in 1971, Stockhausen describes how this piece exemplifies his ‘four criteria of electronic music.’ ‘Unified time structuring’: ‘Many of the various sounds in Kontakte have been composed by determining specific rhythms and speeding them up several hundred or a thousand times or more, therefore obtaining distinctive timbres…sounds pass by, as if you are looking out of the window of a space vehicle, but the line of orientation remains.’ ‘The Splitting of the Sound’: ‘You hear this sound gradually revealing itself to be made up of a number of components which one by one, very slowly leave the original frequency and glissandi up and down…the original sound is literally taken apart into its six components, and each component in turn is decomposing before our ears, into its individual rhythm of pulses. And whenever a component leaves the original pitch, naturally the timbre of the sound changes.’ ‘Multi-layered Spatial Composition’: At the end of the section in Kontakte where the sound is split into its separate components…there are dense, noisy sounds in the forefront, covering the whole range of audibility. Nothing can pierce this wall of sound, so to speak. Then all of a sudden…I stop the sound and you hear a second layer of sound behind it. You realise it was already there but you couldn’t hear it…Building spatial depth by superimposition of layers enables us to compose perspectives in sound from close up to far away…’ ‘The Equality of Tone and Noise’: ‘Traditionally in western music noises have been taboo…the integration of noises of all kinds has only come about since the middle of this century, and I must say, mainly through the discovery of new methods of composing the continuum between tones and noises. Nowadays any noise is musical material…’ It’s easy to see how these methods would have captured the imagination of Japan’s keyboard player and impacted his approach to the creation of sounds.

‘I found out at an early age that I wasn’t going to be able to play keyboards like the people I was watching and the things I was into at the time, which was all the mid-Seventies prog bands,’ he remembered. ‘And it wasn’t until I heard Roxy Music and I loved the glam stuff in the ‘70s and predominantly early ‘80s, I saw that there was another way of doing it. I became more interested in sound than the actual physical art of playing, so I started to develop more complex sounds rather than complex playing. And it just went from there really. I kind of made one note do a lot of things rather than 500 notes with the same sound.’

Sylvian and Barbieri were constrained in their options for these sessions but Barbieri credits this with being the mother of invention. ‘The Tin Drum album was an important one in terms of the synthesis, because we were working with real limitations. I had two synthesisers, an Oberheim OB-Xa and Roland System 700, and David Sylvian had a Prophet 5. That’s a really valuable process for keyboard enthusiasts to go through, to try to do something working with limitations, maybe working with only one synthesiser. Then you tend to find things within it. You can get very lost because there’s so much available now. In the end it’s better to keep to two or three instruments and really get to the bottom of what’s going on with each, and not just play a few presets.’

He cites the ‘prime example’ of his approach of working with one note rather than many as being ‘the intro to ‘Ghosts’ because it’s just one triggered note on the System 700, but I’d programmed in this evolving series of movements with filters, LFOs [low-frequency oscillations] and pitch frequency oscillation. I’ve never been able to quite get that sound again, but it caused havoc for the engineer because there were lots of peaks and it was quite difficult to record.’

Together, through their painstaking synthesiser work, Sylvian and Barbieri crafted the song’s arrangement. ‘At the very early stages it was just his voice with the bass drone. So, he had all the chord changes, there was an arrangement, but it was so minimal. That was one of the tracks that really we just carried on arranging in the studio. It just started building up very gradually with these sounds that were quite influenced by Stockhausen. So, trying to almost take away the structure of the song, as much as we could.

‘David played the three plucked Prophet chords in the choruses and then I did the sustained answer chords on the OB-X…that’s how things used to work, basically. One person would do something and the other would answer with a chord structure or a melody or a hook or something. Then Steve composed that really nice marimba solo in there.’

Jansen was the only other player on the track with Mick Karn sitting this one out. The drummer’s impeccable timing and sense of melody made him the perfect candidate to devise the acoustic break, even if the chosen instrument was not one familiar to him. We first hear the marimba entering the conversation with Sylvian and Barbieri’s synthesisers for the chorus sections before taking centre-stage. Hosting a twitter listening party of Tin Drum with Tim Burgess in 2021, Steve explained, ‘the concept was to make the marimba solo sound naive and clumsy…to give it a sort of nervy edge, but actually I spent hours working on the notation for the right vibe.’

Co-producer Steve Nye gives some fascinating insights into the recording of Tin Drum in an extensive interview for A Foreign Place by Anthony Reynolds. ‘That vocal,’ he recalled, ‘when David first sang it as a guide… There are times when the first time you hear a singer put the vocal onto a track it is a moment of complete transformation. A revelation. Unexpected and instantly recognisable as something special…‘Ghosts’ was one of those occasions. Spine-chilling…A beautifully constructed melody and a lyric that touched something deep inside.’

Sylvian described the evolution that led to such an extraordinary song: ‘It was a slow maturing process. I enjoyed writing ballads and found the slow pieces much easier to compose than up-tempo pieces – they came more naturally to me. Also, it was the influence of traditional Japanese music in its use of space – the emphasis being placed equally on the space as well as the notes played. There were also many other influences. I can pinpoint a few ideas from Stockhausen and Ryuichi Sakamoto’s wife, who recorded an album which used a ballad with very abstract synthesised melody lines behind the vocal. The song arrangements were my idea but a lot of the actual synthesiser sounds themselves came from Richard. Because the ballad is such a recognised form of composition, a song like ‘Ghosts’ allowed me a certain amount of freedom to break down the traditional ballad arrangement.’

The Akiko Yano track to which Sylvian refers may well have been ‘Iranaimon’ from her own 1981 release Tadaima. Co-produced with Ryuichi Sakamoto, the disconnected electronic accompaniment meets Sylvian’s description and may just have helped spark the idea for such a sparse and unconventional setting for his composition.

‘Ghosts’ became seminal in so many ways. It was a pop song, and yet in many ways it represented a deliberate rejection of some of the most familiar characteristics of that form. ‘I persevere with ballads or love songs because that’s the most classic form in pop music,’ the singer later said, ‘so I thought if people understood the form I could take more liberties with it. Maybe ‘Ghosts’ is still the best example.’ He saw a parallel in the visual arts: ‘A lot of the abstract painters used the portrait as a foundation to work from: it gives everybody a way in.’

Decades later, on Manafon, Sylvian was still exploring how far he could push the medium of song to its abstract limits. ‘‘Ghosts’ is like a touchstone in that respect. You can see some kind of the development of that original idea of the deconstruction of the popular song, and you can hear that echoed throughout my work in different periods.’

‘When the room is quiet

The daylight almost gone

It seems there’s something I should know

Well I ought to leave

But the rain it never stops

And I’ve no particular place to go’

Lyrically, the song also marked a watershed moment. ‘In earlier days I had trouble allowing that degree of vulnerability to come through in the work, it was often masked. I didn’t feel comfortable opening myself to that extent. But once I had a breakthrough, and ‘Ghosts’ was a pivotal piece in that sense, it was a breakthrough in which I thought I was able to talk somewhat directly about personal experiences, but in such a fashion that people could identify with it and have it be relevant in their own lives. And once I reached that stage it was a matter of just trying to stay on that path, and there was a struggle between completing a piece like ‘Ghosts’ and then starting out on a new venture like Brilliant Trees: I wrote material and scrapped it, wrote and scrapped it, until something clicked with me.’

We came perilously close to never hearing the song at all. ‘I was very doubtful as to whether to record the piece because I thought it was very personal and the band never particularly liked the slower pieces. I would bring these pieces to them and get these negative reactions so I tended to think that that’s what the public must feel about them.’

By signalling a possible way forward the song strengthened Sylvian’s resolve about his future musical direction and therefore may in some part have hastened the demise of the band. ‘Writing ‘Ghosts’ was a turning point for me. So much of what we created with Japan was built upon artifice. With that song I’d felt I’d had the breakthrough I was looking for. I’d touched upon something true to myself and expressed it in a way that didn’t leave me feeling overly vulnerable.

‘In the coming years I’d forget about all notions of vulnerability, opening up the material to a greater emotional intensity. I knew that I had to find my own voice, both figuratively and literally.’

‘Just when I think I’m winning

When I’ve broken every door

The ghosts of my life

Blow wilder than before

Just when I thought I could not be stopped

When my chance came to be king

The ghosts of my life blow wilder than the wind’

Over 25 years after the song was a hit, Sylvian was asked what was happening inside him when he wrote those words. ‘I was spending more time alone, withdrawing, trying to find answers in what might be described as a relatively unsympathetic environment. The management of that time was extremely manipulative and saw, quite reasonably from a business standpoint, the opportunity for financial return after years of investment but, where in the past I’d been persuaded that my ambitions and goals were in alignment with the management’s, I’d begun to think otherwise.

‘It was the first time I felt independent from both the community of the group itself and the hierarchical pressure of management which worked through me to lead the band, etc. All very strange to look back upon now but we were quite young when we started out and the heavy hand of management stepped in quite early on in our development and we were only too grateful for its presence but, over time, I began to feel the need to side step the constant conspiratorial whispering in my ear, the cajoling advice, subtle puts downs which were designed to create doubt in personal judgement, and just follow my own instincts.

‘So ‘Ghosts’ was born out of that environment. Just when things should’ve, in theory, been getting easier in many respects I was plagued by doubt about where it was I was heading both personally and professionally. I wanted to wrest control from the puppet master and act as my own person, commit to what it was I felt passionately about and do away with the “sideshow” elements.’

Remarkably, the truth of the lyric continued to be revealed to its writer over time. ‘When I wrote ‘Ghosts’ it was after a very dark period I went through. I wrote the piece and thought, “Yes, that sums it up very well.” But after I recorded it, after it had been a hit, I went through an even darker period and I thought: “This is what it’s really about.” I hadn’t experienced it the way I thought I had, and yet the song summed up that period very well. It was a very bleak time – every time you thought you were getting somewhere, something would stand in your way.’

‘Ghosts’ was released as a single nearly five months after Tin Drum had hit the racks in the record stores. Certainly out of keeping with the radio playlists of 1982, it was a surprise choice. ‘I had immense faith in that track from the beginning,’ Sylvian remembers, ‘and urged Virgin to release it as a single, so it didn’t come as a complete surprise to me that it was as successful as it was. Very gratifying all the same of course.’

It would be Japan’s highest charting single, rising to No 5. Many fans would pinpoint the moment that their fascination with the band was born as the performance of the track on the BBC chart show Top of the Pops. There was no video with a manufactured storyline narrowing down the interpretation of the song, just a classy rendition in a dry-ice filled studio of a song that could take on individual significance for every viewer. Mick Karn is restored to the line-up at the keyboard whilst Sylvian delivers the vocal straight to camera. The impact was significant. ‘We are no longer the same after hearing certain sounds,’ to steal the Stockhausen quote at the outset of this article. At the time of the TOTP appearance the single was placed at No 42 in the charts, Japan’s performance sending it into the Top 2o.

Top of the Pops, originally broadcast 18 March 1982

It was an important moment for fans and band alike. Sylvian: ‘When ‘Ghosts’ was successful finally in the UK as a single it just gave me the encouragement that it’s possible to be as open and as honest as I would like to be and there’s an audience out there for this kind of music.’ Barbieri: ‘The big achievement is ‘Ghosts’ on Tin Drum, because it’s such an adventurous and strange piece of music that we got onto Top of the Pops and had a Top 5 single with that. It’s something I’m really proud of.’ Steve Jansen: ‘‘Ghosts’ – What to say about this…an outstanding composition. Highest chart position despite being stripped to its essence. Best vocal performance – found that comfort zone. Only Japan track Mick doesn’t play on. Only Japan track I play a solo on.’

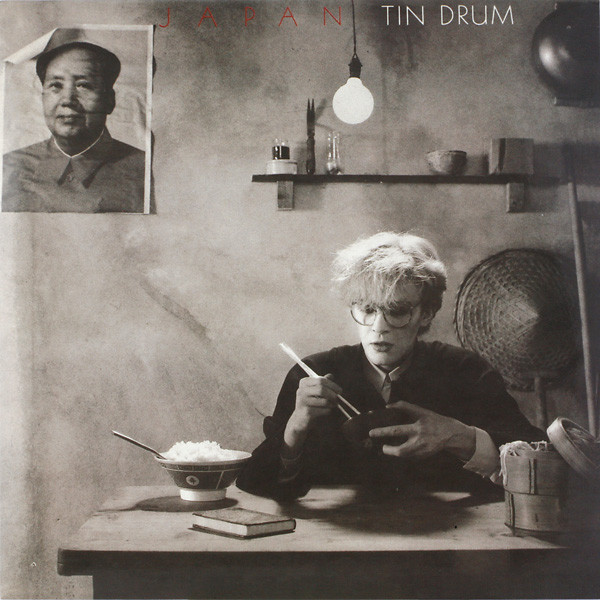

It was the perfect package, and that extended quite literally to the exquisite cover art. The 7″ and 12″ single covers had differing monochrome shots of a bespectacled Sylvian, pictured at prayer in the first and with hand running through hair in the larger format. A picture disc had both portraits, one on each side of the vinyl. The photographs look like they come from the same session, but in fact Steve Jansen took the former and Yuka Fujii the latter. Jansen: ‘They were not taken at the same time, as far as my memory serves – I don’t even know which session came first. Mine were taken on the roof of my London flat which was only accessible via a very difficult to negotiate skylight suspended over a deep stairwell (and this was not a flat roof) and the purpose was to experiment with infra-red film, but as it turned out the location had no bearing whatsoever on the shot used for the cover.’

How amazing to discover after decades that this striking pose was captured on the rooftop at Stanhope Gardens in Central London. Pictures shared by Steve on twitter as part of the Tin Drum listening party show just how precarious the location was for all participants.

The band was already disintegrating by the time ‘Ghosts’ hit the charts, and once the final tour was over and the news of the split made public, Sylvian appeared on the BBC arts programme Riverside, performing the song solo in a stripped-back arrangement with twelve-string acoustic guitar.

Riverside, originally broadcast 20 November 1982

I love to play ‘Ghosts’ side by side with another Stockhausen piece that to me is reminiscent of the sounds later created by Barbieri and Sylvian. Studie II pre-dates Kontakte having been created in 1954 and marks a milestone in the history of music as it was the first published score of electronic music. The ’50s electronics innovator meets ’80s Japan pop sensibility.

‘Ghosts’

Richard Barbieri – keyboards, keyboard programming; Steve Jansen – marimba; David Sylvian – keyboards, keyboard programming, vocal

Music and lyrics by David Sylvian

Produced by Steve Nye & Japan. From Tin Drum, Virgin, 1981

Lyrics © samadhisound publishing

‘Ghosts’ – official YouTube link. It is highly recommended to listen to this music via physical media or lossless digital file. If you are able to, please support the artists by purchasing rather than streaming music.

Download links: ‘Ghosts’ (Apple), ‘Studie II’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Tin Drum (Amazon), Stockhausen Complete Edition CD No 3 – Elektronische Musik 1952-1960 (karlheinzstockhausen.org)

Full sources and acknowledgments for this article can be found here.

Thank you to Steve Jansen for permission to include his photographs in this article. Steve has a range of photographic prints available for sale at his website, here. These are always meticulously reproduced.

Steve Nye’s full interview about the making of Tin Drum can be found in A Foreign Place, Anthony Reynolds’ biography of Japan (burningshed).

‘There’s really very few parameters that define what a pop song can and can’t be, after all songs such as ‘Ghosts’ and ‘O Superman’ were top five material and, in essence, the pop song is a seductive proposition… No wonder people return to these forms again and again.’ David Sylvian, 2010

I can relate completely, to the first paragraph. Fifty years ago, in 1971, I became a true fan of popular music, as glam emerged and have remained one, since. When the core of the group of individuals, that became Japan, came together at school, I believe, in 1974, they were deciding who would play which instrument and began learning and creating. By the time of ‘Ghosts’ (1982), their ability was obvious and in my view they could at least match Roxy Music (my own personal favourites) in musical virtuosity and style, in synthesizing sometimes quite simple parts of their own original unique ‘soup’, into something more complex and melodic. I sometimes miss them – my contemporaries, the times, but I’ll never miss the music, I’ll always have some of it (right now it’s less than a foot or c.300mm away) whilst I’m here…Compliments of the season to all and my best wishes…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for being here Jeremy, and compliments of the season to you too.

LikeLike

Imho your essays possess the extremely rare quality of conjuring completeness from conciseness.

Reading you as always gives me the best rewarding 10 minutes I could ever spend sitting in front of my laptop.

Once again thank you, David, for this umpteenth watercolour of yours that widens new perspectives in hearing, thinking, connecting, understanding music and life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for such generous feedback. I can only say that I’m grateful that you take time to read the articles and find them of some value. Sincere thanks again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your ongoing perception and informed writing about this music.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Rupert.

LikeLike

Great article..loved Japan and still do.♡ Followed them since 78 Music Machine Gig etc and saw them many times and DS Solo.Their evolution as a band was always interesting.Polaroids was a particular fav as was Tin Drum.Forever stylish.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thankyou for all your wonderful informative articles in this blog, i genuinely look forward to them. A happy xams to you and i wish you well for 22. Please keep up the good work. Thankyou again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks, Declan. I shall try to keep the articles coming in 2022.

LikeLike

Interesting to note in SYL/ERR book that one of the pages shows he was listening to Dave Holland/Zakir Hussain (Good Hope > J Bhai). Apple link here: https://music.apple.com/ca/album/j-bhai/1474680581?i=1474680592

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLike