The initial session that David Sylvian and Dai Fujikura held with musicians from the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) in New York yielded material for their first-released collaboration, ‘Five Lines’, together with string parts that were intended for incorporation into Manafon but were ultimately omitted from that album’s mixes. By the time of the second session with ICE, there was an agreed vision for a project based around re-imaginings of the Manafon material, a number of the tracks with the benefit of Fujikura’s string arrangements (read more here).

Fujikura was also keen to extend his collaboration with Sylvian by developing further original material. ‘The Last Days of December’ became the next instalment in the pair’s musical explorations. ‘With this piece,’ Dai explained, ‘from my experience of ‘Five Lines’, I thought I should just give David materials, a simple series of chords played in a very strange way, and not think about his vocal line. That’s his job! But also I thought I should give him more than the “necessary materials”, so that he can eliminate things to create the track he wants.’

The presence of flautist and ICE co-founder Claire Chase at the New York sessions presented some intriguing possibilities, given her mastery of playing using extended techniques. ‘I say “simple chords”,’ Fujikura continued, ‘but I derived the chords from the multiphonics of the bass flute [Dai’s description of multiphonics being ‘a technique that uses special fingering to produce two or more sounds simultaneously from one wind instrument’]. As I am not an improviser, when I write multiphonics in my compositions, I expect exact multiphonics with particular pitches. I even write the fingering of the instrument to get those multiphonics.

‘So I knew which particular pitches I was going to get out of the bass flute multiphonics, and I developed the harmony from that for strings. They sustain the chords, but slowly they change the dynamics and also sonority, going from smooth playing to bowing near the bridge (molto sul ponticello). It sounds as if you are increasing the level of compression, but we are doing it acoustically.

‘ICE is particularly good at performing these kinds of extended techniques, as they specialise in contemporary music. If you get normal session musicians, they won’t be able to achieve these techniques.’

The sound of the multiphonics, carried over into the string arrangement, gives the effect of a discordant drone that eerily undergirds Sylvian’s voice. ‘In a number of our exchanges regarding possible future directions in music we’d discussed the drone and its place in both classical and popular music, plus its continued presence in my own work,’ said Sylvian. ‘Dai was, and continues to be, interested in shifting the root of the drone, attempting to make the root somewhat ambiguous which should in a sense liberate the vocal melody…hence Dai’s interest in serving up something of this nature at the second session in New York. There is a bass flute playing multiphonics more or less throughout the entire piece which adds a disquieting harmonic element to the piece, and which haunts the vocal melody as it attempts to find its way through and around the resulting tonal density. The lyric itself reflects this haunting with ghosts of its own.’

Died in the Wool contains allusions to several poets. There are two poems by Emily Dickinson set to music (see ‘A Certain Slant of Light’) and the pair of tracks ‘Anomaly at Taw Head’ and ‘Anomaly at Taw Head (A Haunting)’ certainly concern Ted Hughes, the geographical reference being to the location of a granite memorial to the late poet.

‘The Last Days of December’ very likely recounts the final hours of Hughes’ first wife, the American poet Sylvia Plath. It’s a return to the subject of suicide after the references found on Manafon:

‘My suicide, my better days

There’s nothing I regret’

‘Small Metal Gods’

‘Here we are then, here we are

Notes from a suicide’

‘The Greatest Living Englishman’

The theme is a recurring one in the late samadhisound era recordings. In 2014, Sylvian would preface his introduction to his collaboration with the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Franz Wright, there’s a light that enters houses with no other house in sight, with the following quotation:

‘There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.’ The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus

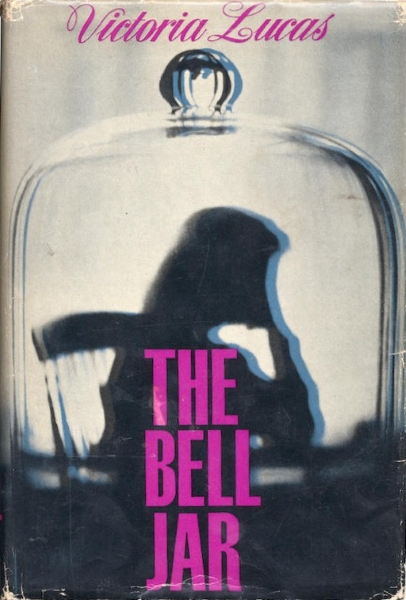

Sylvia Plath’s only novel, The Bell Jar, is both a vivid portrait of 1950s society in New York and a depiction of an individual’s struggle with mental illness and descent towards attempted suicide. Some events and characters in the book are based upon Plath’s personal experience. ‘I think it will show how isolated a person feels when he is suffering a breakdown…,’ Plath wrote to her mother. ‘I’ve tried to picture my world and the people in it as seen through the distorting lens of a bell jar.’

The image of the laboratory vessel bell jar conveys the oppressive impacts of depression and mental anguish, and perhaps also the artificial constraints imposed upon a female’s life by the societal norms of the time.

‘To the person in the bell jar, blank and stopped as a dead baby, the world itself is a bad dream.’ The Bell Jar

The struggles of the protagonist, Esther Greenwood, lead her to contemplate various means of ending her own life.

‘The thought that I might kill myself formed in my mind coolly as a tree or a flower.’

‘But when it came right down to it, the skin of my wrist looked so white and defenceless that I couldn’t do it. It was as if what I wanted to kill wasn’t in that skin or the thin blue pulse that jumped under my thumb, but somewhere else, deeper, more secret, and a whole lot harder to get.’ The Bell Jar

Sylvia Plath spent the last weeks of 1962 living alone with the young children she shared with Ted Hughes, Frieda (then aged 2) and Nicholas (born that January). Hughes had moved out of the family home as the couple’s intense six-year marriage disintegrated amid fierce rows about his assignations with Assia Wevill.

Esther Greenwood, Sylvia’s alter-ego in The Bell Jar, found this time of year – the last days of December – to be consistently hollow with unfulfilled promise:

‘It was the day after Christmas and a grey sky bellied over us, fat with snow. I felt overstuffed and dull and disappointed, the way I always do the day after Christmas, as if whatever it was the pine boughs and the silver and gilt-ribboned presents and the birch-log fires and the Christmas turkey and the carols at the piano promised never came to pass.’ The Bell Jar

On 11 February 1963, Plath took her own life, while her husband was in the arms of another woman. Jonathan Bate writes in Ted Hughes, The Unauthorised Life (2015), ‘The coroner’s inquest recorded a verdict of “Carbon Monoxide Poisoning (domestic gas) whilst suffering from depression.” Sylvia had taped up the kitchen and bedroom doors, and placed towels underneath, to stop the gas spreading through the rest of the flat. Then she had placed her cheek on a kitchen cloth folded neatly on the floor of the oven and turned on the taps of the cooker. The bedroom window was wide open and she had left bread and milk by Frieda and Nick’s high-sided cots.’

‘What shall we tell them

A honeymoon brief as a walk in the park?

What shall we tell them when they ask

And they’ll ask

Could you not see another way out?’

The ‘them’ of the lyric could be the children. How to explain their mother’s action and absence? Equally, it could refer to the public, for whom the relationship between Hughes and Plath was a subject of great interest and the circumstances of their separation a catalyst for heated debate for years to come. Was Plath’s suicide the result of mental illness that pre-dated her marriage, or was Hughes to be blamed for his wife’s demise?

‘Was the place without sun, was it furnished in black

With the ache of the gas oven there at your back?

A death angel paces in boredom and waits

It shrieks from dark corners undermining your faith’

‘I was so scared, as if I were being stuffed farther and farther into a black, airless sack with no way out.’ The Bell Jar

‘Your sanity shattered and climbing the walls

Wet towels at the floor line stuffed under the doors

And the beating of powder-black wings left you blind

The last days of December are the loneliest kind’

The fictional Esther Greenwood and her creator Sylvia Plath shared a viewpoint that the first nine years of their lives were their happiest times. ‘I thought how strange it had never occurred to me before that I was only purely happy until I was nine years old’ (The Bell Jar). For both character and author these years were brought to an abrupt end by the death of their father. Plath’s childhood was full of memories of a carefree life on the coast, as recorded in her essay Ocean 1211-W, which closes: ‘And this is how it stiffens, my vision of that seaside childhood. My father died, and we moved inland. Whereon those nine first years of my life sealed themselves off like a ship in a bottle—beautiful, inaccessible, obsolete, a fine, white flying myth.’

‘Where were the cape and the coastline

The wonder kid’s sunshine?’

The newly wed Hughes and Plath had spent happy times in Benidorm, Spain in 1956 and then a second honeymoon in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, the following year. Just a few years later their marriage had hit rock bottom and Sylvia had lost touch with her own identity and what it was that made life worth living.

Sylvian’s lyric seems to assume Hughes as narrator (‘the lies that I told…’) and touchingly describes how bereft Plath was in that moment of crisis:

‘In the exit you made there was no pause for thought

‘Cause the lies that I told were the lies that you bought

There was no place to find you no you to be found

In the margins of books you were reading

There are stages to grieving that won‘t let you down’

‘I’m not afraid of being lost. We all wander off from time to time. It’s the fear of never quite finding myself that keeps me up at night.’ The Bell Jar

In 2010 the arts critic and broadcaster Melvyn Bragg discovered an unpublished poem by Ted Hughes amongst the former Poet Laureate’s archive of papers which are now held by the British Library in London. ‘Last Letter’ reflects on Plath’s final hours, asking, ‘What happened that night? Your final night.’

‘What happened that night, inside your hours,

Is as unknown as if it never happened.

What accumulation of your whole life,

Like effort unconscious, like birth

Pushing through the membrane of each slow second

Into the next, happened

Only as if it could not happen,

As if it was not happening.’

Over 20 years after Plath’s death, a court case was brought by an individual who accused the makers of a film of The Bell Jar of defaming her and causing distress on the basis that a character in the novel and hence the movie was based upon her own identity. Covering this episode in his biography of Ted Hughes, Jonathan Bates writes, ‘Nobody could deny that The Bell Jar was centred on Sylvia’s break-down and the trauma of her attempted suicide. Hughes accordingly reasoned that he would have to argue that it was a fictional attempt to take control of the experience in order to reshape it to a positive end. By turning her suicidal impulse into art, Sylvia was seeking to save herself from its recurrence in life: she was trying “to change her fate, to protect herself – from herself” but as an “attempt to get the upper hand of her split, her other personality, to defeat it, banish it, and in the end, extinguish it” it was ultimately a failure.

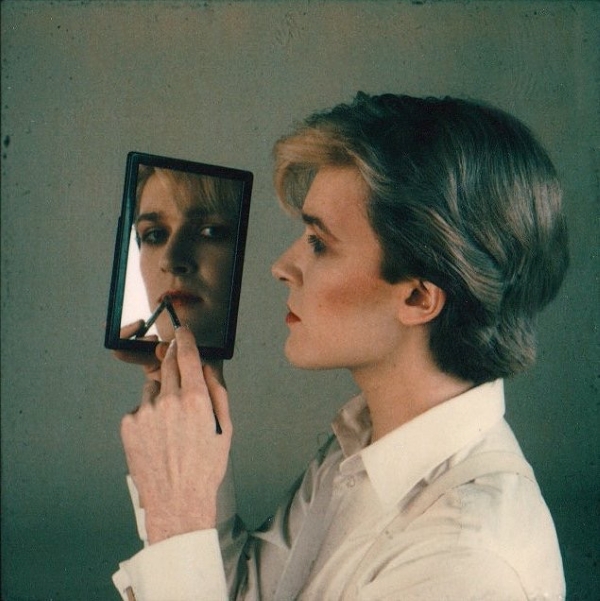

‘The notion of the “split” or “other personality” in Plath was something to which Hughes returned again and again; it was also an obsession of Plath herself, already manifest in her 1956 undergraduate honours thesis at Smith which was entitled The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoevsky’s Novels.’

In May 2018, The Los Angeles Review of Books published an article entitled Sylvia Plath’s Magic Mirror by Kelly Marie Coyne. The article made reference to Plath’s undergraduate work and made the case that ‘the duality that Sylvia Plath wrote about in her thesis provides the basis for the personality of Esther, the protagonist of Plath’s The Bell Jar.’ It traces how the main character’s double personality is articulated through episodes in the novel, including her use of the nickname Elly and the use of mirrors as a recurrent device.

‘I moved in front of the medicine cabinet. If I looked in the mirror while I did it, it would be like watching somebody else, in a book or a play.’ The Bell Jar

David Sylvian shared Coyne’s article online on the day of its publication, as the first in a pair of messages. ‘Double 1/2’ contained the link to Sylvia Plath’s Magic Mirror, while ‘Double 2/2’ was simply accompanied by one of Jill Furmanovsky’s ’80s photographs of Sylvian, applying make-up to his own image in a mirror.

Claire Chase’s 2012 album Terrestre includes the track ‘Glacier For Solo Bass Flute’ composed by Dai Fujikura which provides us with a contemporaneous composition to pair with ‘The Last Days of December’. ‘This passage was originally taken from the last section of my ensemble work called ICE,’ explains Dai, that piece having been ‘written for ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble) in the USA, the oldest ensemble who I have a working relationship with. They are like my family. However this is the first piece I have written especially for them.’

The bass flute finale ‘was then developed into a stand-alone solo piece. In my imagination this piece is like a plume of cold air which is floating silently between the peaks of a very icy cold landscape, slowly but cutting like a knife…’

A performance of Dai Fujikura’s ‘Glacier ‘ by Claire Chase in 2015 at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York, 2015

‘The Last Days of December’

Erik Carlson – violin; Jennifer Curtis – violin; Claire Chase – bass flute; Margaret Dyer – viola, Chris Gross – cello; David Sylvian – vocal

Strings and flute composed and conducted by Dai Fujikura

Strings recorded by Ted Young at Magic Shop Studios, NYC

Music by Dai Fujikura and David Sylvian. Lyrics by David Sylvian.

Mixed by David Sylvian & Dai Fujikura.

Produced by David Sylvian. From Died in the Wool, Samadhisound, 2011.

Lyrics © samadhisound publishing

‘The Last Days of December’ – official YouTube link. It is highly recommended to listen to this music via physical media or lossless digital file. If you are able to, please support the artists by purchasing rather than streaming music.

All artist quotes are from interviews in 2011 unless otherwise indicated. Full sources and acknowledgments can be found here.

The featured image is by George Bolster from the inner-sleeve art of the 2025 vinyl release of Died in the Wool.

Sylvia Plath’s novel The Bell Jar can be purchased here.

The Los Angeles Review of Books article Sylvia Plath’s Magic Mirror by Kelly Marie Coyne can be read here.

Dai Fujikura’s website contains a wealth of material about his work – daifujikura.com. Details of all releases on his Minabel label can be found at minabel.com.

Dai’s book, Too Soon for an Autobiography, published in Japanese, is available here.

Download links: ‘The Last Days of December’ (Apple), ‘Glacier for solo bass flute’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Died in the Wool (Amazon) (vinyl re-issue burningshed); Terrestre (Amazon)

‘It became my second collaboration with David. David’s voice that I have known since childhood, the bass flute’s multiphonics, and the sounds of the stringed instruments that come from the strong pressure of the bow on the strings blend well together to create a fascinating melody and beautiful words that are unique to David. I really like this track.’ Dai Fujikura, 2022