Teenage musical memories often take hold for a lifetime. Early in the ’80s a friend of mine held a party at his family’s home. These were always good nights, an opportunity to spend time with friends outside of sixth form classes and the common room at school. A time to enjoy the music that was in and around the charts, and favourite past tracks from Bowie and others. At the end of the evening, most people having by now drifted away, someone took out the vinyl of Gentlemen Take Polaroids and dropped the needle mid-way through side B for ‘Nightporter’. I knew the song, of course, but here it was being played on a quality sound system and at a volume that wouldn’t have been possible back at home. The person who selected it then sat cross-legged on the floor, head bowed, eyes closed, transfixed by the music.

The simple repeating piano melodies, anchored in the bass notes of the left hand, with the overlay of oboe, bowed double bass, and long keyboard lines, come together in a heady mix with a lyric that betrays some specific inner turmoil within the heart of the song’s protagonist. It’s music that carries a sense of its own gravity, rising to a crescendo in the wordless singing of the final section. ‘Nightporter’ occupied that space unchallenged until the final note had slowly decayed into silence.

First person lyrics do appear elsewhere on Gentlemen Take Polaroids, but those are more matter of fact:

‘Now there’s a girl about town

I’d like to know

I’d like to slip away with you’

from ‘Gentlemen Take Polaroids’

…or in some cases downright obscure:

‘And I’ll drive safely inside my car

Taking islands in Africa’

from ‘Swing’

As the album draws towards its conclusion, with only the Ryuichi Sakamoto collaboration ‘Taking Islands in Africa’ to follow, the introspection goes deeper for ‘Nightporter’. Details of the situation described are shrouded in mystery, yet somehow that only adds to the potency, each listener free to identify the sentiments with their own circumstance:

‘Could I ever explain

This feeling of love, it just lingers on

The fear in my heart that keeps telling me

Which way to turn?’

The rain-soaking may be an actual event or an image to convey an emotional experience, but in the perfect articulation of a space occupied by real people – ‘the width of a room’ – we are transported to a physical location, somewhere we can recognise:

‘We’ll wander again

Our clothes they are wet

We shy from the rain

Longing to touch all the places we know we can hide

The width of a room

That could hold so much pleasure inside’

Sylvian would often borrow from other art forms to embellish his own lyrics and here the song’s curious title is taken from the 1974 film The Night Porter, directed by Liliana Cavani and starring Dirk Bogarde and Charlotte Rampling. It’s a highly controversial movie that focuses on the sadomasochistic relationship between a former Nazi officer and one of his inmates, with events from the concentration camp relived within the context of their passion – making deeply uncomfortable viewing for many. The film’s title is a reference to the occupation of Bogarde’s character after the war as a hotel night porter.

Later Sylvian would recollect that he had read Bogarde’s poetry in the late ’70s, adding regarding his career in cinema: ‘I did enjoy Bogarde’s mid to late period. It’s good to be reminded of this. His best films don’t seem to have appeared on DVD even though they were by celebrated directors such as Resnais and Fassbinder. I think my take on them would be very different now but it was an interesting and brave career move for Bogarde to choose to make them’ (2010). Sylvian admired the actor’s pursuit of his artistic goals and the shunning of a more lucrative but less creatively fulfilling path, as he turned his back on the mainstream in favour of making European art movies.

Perhaps the sound of the words Night Porter simply appealed, perhaps there is a direct allusion to the depths of attraction portrayed in the film – ‘love comes always with a price to pay,’ said director Cavani. Sylvian’s lyric leaves things open for the listener to draw their own conclusion:

‘Here I am alone again

A quiet town where life gives in

Here am I just wondering

Nightporters go

Nightporters slip away’

I’ve always thought of the ‘nightporters’ as conveyors of the fears and longings that take hold of one’s mind in the middle of the night. It’s a purely personal connection and one that resonates with the ‘ghosts’ that would be referenced in the song of the same name on Japan’s following album, Tin Drum (see more here).

Sylvian himself saw a connection between the two tracks in the authenticity of their expression. ‘You could say that the first two Japan albums were an act of concealment, and from that point onwards the act of creating [subsequent] albums was trying to pare away all of that, and trying to let something of myself come through, to allow myself to be that vulnerable. And I reached that point with ‘Ghosts’, that was the breakthrough. But getting there, there was ‘Nightporter’ and there were other bits and pieces that spoke of emotional states that were very, very real to me. But they were dressed up in other storylines or ideas that I came up with.’ (2001)

‘It’s a very romantic number,’ he observed, noting ‘a sense of isolation and melancholy, as many people are apt to point out. And I think that’s very indicative of my state of mind at the time. I was very isolated and not a particularly happy character at that point in my life. But other than that, it’s pure fantasy…

‘‘Nightporter’ is one of the earlier pieces that I wrote on keyboards. I remember getting my first keyboard prior to writing the Quiet Life album and that’s one of the things that influenced the more quiet approach, the more melodic approach to that particular album… ‘Nightporter’ was on the …Polaroids album and so I was still exploring the keyboard.’ (1993)

The piano lines are deliberately crafted in the style of the French composer Erik Satie (1866-1925). During a radio interview promoting Japan’s previous LP, Quiet Life, Sylvian had acknowledged the influence of ‘a guy called Eric Satie,’ and there’s a distinct line to be traced between ‘The Tenant’ which closes Obscure Alternatives, ‘Despair’ from Quiet Life – with its French language lyric reference to the ‘desespoir agréable’ (pleasant anguish) of the artistic life – and then ‘Nightporter’ on Gentlemen Take Polaroids.

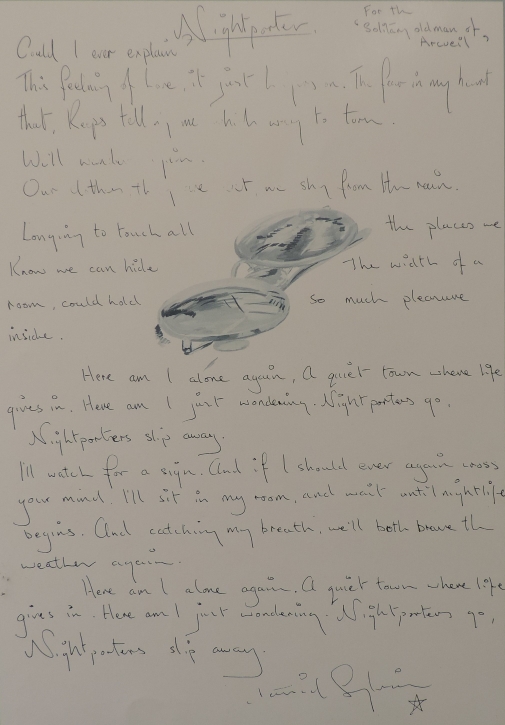

Anyone familiar with Satie’s Trois Gymnopédies will instantly make the connection with Japan’s song. The brochure for the band’s 1982 Sons of Pioneers tour carried the ‘Nightporter’ lyric in Sylvian’s handwriting, a dedication reading, ‘For the “solitary old man of Arcueil”.’ The inscription tells us that the writer knew something of Satie’s life story rather than solely being attracted to his music. The Trois Gymnopédies were completed by Spring 1888 when Satie was in his early twenties, each subtitle transmitting a mood: ‘lent et douloureux’ – slow and painful, ‘lent et triste’ – slow and sad, and ‘lent et grave’ – slow and serious. For all their familiarity to us over a century later, and despite contemporary praise in some circles, they did not propel the composer to either fame or fortune. In the following years the pieces were orchestrated by Satie’s friend Claude Debussy, a development which led to an increase in popularity, but the composer was living in quite desperate circumstances in a small room that was unheated and without running water. In 1898, with no money and poor prospects, Satie rented a room in the working-class Paris suburb of Arcueil. He would walk the 6-mile distance into the centre of the city most days and it was reliably recorded that once he had taken up residence in Arcueil, ‘no-one set foot in his room during his lifetime.’ Solitary indeed.

‘I’ll watch for a sign

And if I should ever again cross your mind

I’ll sit in my room and wait until night life begins

And catching my breath we’ll both brave the weather again’

The musical echoes weren’t lost on an interviewer for ZigZag magazine. ‘The ‘Nightporter’ song on …Polaroids is very Erik Satie,’ came the observation, coupled with the declaration, ‘If I’d written it, I’d be highly embarrassed!…Because it’s so similar.’

Richard Barbieri acknowledged that the composition was ‘exactly the same’ as Satie’s work, but explained, ‘We’d be the first ones not to want to make a hash of something Erik Satie stood for and that’s why we’re pleased with it because it’s so close.’

‘It’s more a tribute to him,’ said Sylvian. ‘We could have just taken one of his actual tracks and put vocals to it but then we’re destroying something that maybe wasn’t his original intention, so the idea was to do something quite close. Someone was saying the other day that people compare us all the time to different things because we’re not influenced by normal sources so if we took a normal rock’n’roll riff people wouldn’t say, “well don’t you think you’re really stealing from so and so?”’

Barbieri agreed that Japan’s unusual reference points left them more open to criticism: ‘It’s because the songs have been influenced by something relatively untouched that they notice that.’

Tribute, pastiche or ‘plunder’ (to quote the ZigZag interviewer), the piano parts are put together with a good deal of ingenuity. The full-length version of the track includes a delightfully constructed piano interlude that sounds like it could be a lost instalment of the Gymnopédies. And, of course, the dancing oboe, synth lines which rise in prominence as the track develops, and vocal delivery all take the piece beyond the scope of the original inspiration. Sylvian certainly saw it that way: ‘Using an arrangement that pulls from 20th-century French classical music? It’s just a twist, nothing more than that. That song isn’t dependent on that particular influence, it just added to its atmosphere.’ (2009)

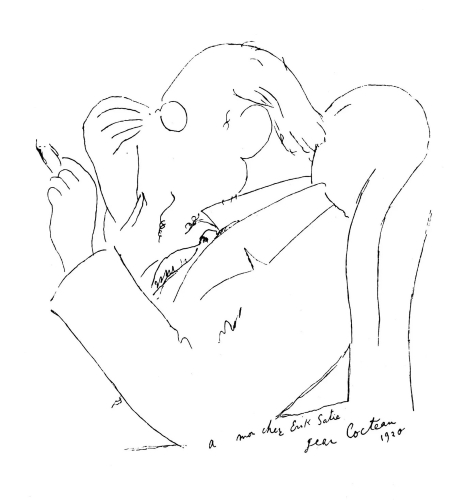

Later in his life, Erik Satie was friend and collaborator with both Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso, in particular for the ambitious ballet Parade. Sylvian was no doubt aware of the connection. The 1982 hand-written lyrics for ‘Nightporter’ couple his signature with Cocteau’s familiar star symbol and, in the months that followed, his album Brilliant Trees and associated singles would bear witness to the influence of both Picasso and Cocteau (see ‘The Ink in the Well’ and ‘Pulling Punches’). Not long afterwards, Sylvian would profess an interest in Rosicrucianism which may have been piqued in part through Satie who was closely involved in a branch of the sect for several years in the 1890s, performing at the Salon Rose+Croix and composing works such as Trois Sonneries de la Rose+Croix.

Satie’s use of repetition, for instance in his piece Vexations – the motif of which the composer appears to instruct should be played ‘840 times in succession’ – later caught the imagination of John Cage who staged a rendition of the piece performed in relay and lasting for over 18 hours. Repetition was also at the heart of Satie’s musique d’ameublement – “furniture music” – which was designed to be heard in the background rather than to be listened to intently and is seen by many as a forerunner to muzak and the ambient genre.

Interestingly, between the release of Gentlemen Take Polaroids and the subsequent Tin Drum, Sylvian told Sounds: ‘I love repetition. I love things that just go on and on and on, I’ve based nearly everything we’ve done on that. If you repeat any sound constantly, as long as it’s pleasant or interesting, it becomes hypnotic. The same with Warhol and his soup cans.

‘The idea is to take the listener and draw them in, then the listener goes off on a parallel of their own, taking in the essence without really listening to the music, which I think is the most important way to listen to music.

‘Then they begin to associate the sounds they’re hearing with things in their own lives, fantasies in their lives, and that’s when a piece of music becomes really personal to you. That’s what I always try to do. It may sound clumsy, but you can’t put it into words. It’s just worth it to see someone go off into their own world.’

Perhaps it’s not a stretch too far to see references to both ‘Nightporter’ and Satie in the album’s cover, with Sylvian sheltering from the weather beneath an umbrella, an item traditionally associated with the French composer who would carry one on his walks from Arcueil to central Paris and by all accounts collected them.

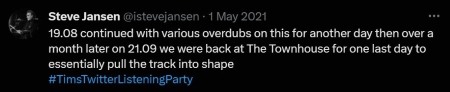

Steve Jansen’s meticulous approach to journaling means we can trace some details of the track’s recording. Looking back on his notes for an online listening party in 2021, Steve shared that sessions for Gentlemen Take Polaroids began at The Townhouse studios in London in July 1980, where the title track and ‘Ain’t That Peculiar’ were recorded. Proceedings then moved on to Air studios in the heart of the city and it was here that most of the numbers were crafted, ‘Nightporter’ being the penultimate album track worked on – the last being the late addition ‘Burning Bridges’ which was worked on at The Barge.

Regarding ‘Nightporter’ he noted that on 18 August 1980, ‘Richard recorded the piano probably with a Waltz drum machine pattern at a really low level in his headphones so the piano mic’s wouldn’t pick it up.’ It was a memorable day for other reasons too: Mick Karn was admitted to hospital for an operation – most probably the removal of his appendix according to Jansen. Work on the song continued during his hospital stay which lasted until 22 August.

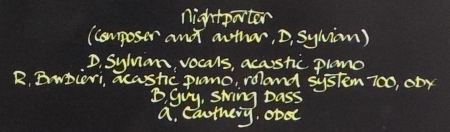

The tour brochure for Japan’s 1981 The Art of Parties tour contains credits for each track on Gentlemen Take Polaroids that are more detailed than those appearing on the album sleeve. Here we learn that Sylvian and Barbieri are the only members of Japan to perform on ‘Nightporter’, each contributing to the piano parts with Richard’s synth constructed on his Roland System 700 and Oberheim OB-X. We also discover that rather than being performed by Mick Karn, the oboe part was played by Andrew Cawthery, who had previously worked with Ann O’Dell, orchestrator for the Quiet Life album.

It’s also interesting to find that it was Barry Guy who plays the bowed double bass on the track. Guy is a veteran of the free improvisation scene and by this time had played and recorded with both Derek Bailey and Evan Parker who would appear much later on David Sylvian’s samadhisound era releases, Blemish and Manafon.

When the song eventually became a single, an additional note on the sleeve told us that the ‘string bass and oboe’ were arranged by Mick Karn and O’Dell.

Explaining the sharing of the acoustic piano part in Anthony Reynolds’ biography of Japan, A Foreign Place, Richard Barbieri said, ‘I think it was just a case of one of us playing the chordal and bass parts and the other playing the top lines. We may have recorded that together as one take. There was always a rush for the piano and often two people were playing at once.’

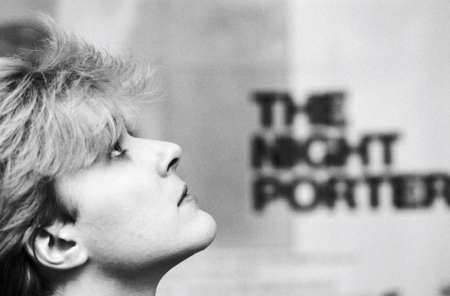

‘Nightporter’ was issued by Virgin as a single to follow up the previous 45s drawn from Tin Drum, the release timed a week ahead of Japan’s run of six shows at London’s Hammersmith Odeon as part of their final, Sons of Pioneers, tour. Remixed by Steve Nye, it became their third Top 30 hit of the year after ‘Ghosts’ and ‘Cantonese Boy’. I didn’t know how to feel about it at the time, a treasured album cut from …Polaroids being promoted in this way, and in particular the single edit lost some of the majesty of the full-length track. That said, the packaging was exquisite, incorporating two Yuka Fujii shots of Sylvian silhouetted by light pouring in from a sash window, the singer seated on the 7″ and standing on the 12″. Everybody wanted to own one of those coats that he was wearing…

A simple promo video was produced to support the single, evidently captured on the tour but featuring only Sylvian at the piano and Karn now playing the oboe that he had arranged.

‘Nightporter’ promotional video

‘Nightporter’

Richard Barbieri – acoustic piano, Roland System 700, OBX; Andrew Cawthery – oboe; Barry Guy – string bass; David Sylvian – vocals, acoustic piano.

String bass and oboe arranged by Mick Karn and Ann O’Dell

Music and lyrics by David Sylvian

Produced by John Punter. From Gentlemen Take Polaroids, Virgin, 1980.

The 1982 single version was remixed by Steve Nye

lyrics © copyright samadhisound publishing

All artist quotes are from 1981 unless otherwise stated. Full sources and acknowledgements for this article can be found here.

Download links: ‘Nightporter’ (Apple); Gymnopédie No 1 (Apple); Gymnopédie No 2 (Apple); Gymnopédie No 3 (Apple)

Physical media links: Gentlemen Take Polaroids (Amazon); Trois Gymnopédies (Amazon)

Steve Jansen’s twitter listening party for Gentlemen Take Polaroids can be replayed here. Steve has a significant number of prints available for sale including the shot of Sylvian in front of the poster for The Night Porter. These are always exquisitely produced. More information here.

‘I was influenced an awful lot by Satie, but I’ve milked him dry after ‘Nightporter’. People like Satie and Warhol influenced me a lot, but I don’t really like their art that much, just the ideas behind it. I adopt their ideas and apply it to my work.’ David Sylvian, 1981

The alternate cover shot makes a very different communication.

Just to say how this song has felt like a balm to my soul ever since hearing it at fourteen years old. Fourty years on its magic remains.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderful song from a great album. It was a shame that the band could not continue after Tin Drum, you could just imagine what could have happened. Rain, Tree, Crow was disappointing and I think too much time had passed. I love David’s solo albums but have special affection for Gentleman and Tin Drum in particular and Nightporter is such a lovely ballad. I have to say Japan’s music has not aged at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that, during the period 1980-1982 inclusive, Japan didn’t put ‘a foot wrong’. I agree strongly with Michael’s second sentence (above), though maybe also appreciating, why it had to stop…

This may be just my own bias/taste/pleasure, but I can’t help but feel that ‘Nightporter’ is also (at least unconsciously) influenced by Bryan Ferry’s, ‘All Night Operator’ (1976/77), from his album, ‘In Your Mind’, whilst quite different, in context, tempo and mood.

“…And if I should ever again cross your mind…” (Sylvian). The personnel involved with the realisation of each of those songs, Ann O’Dell, Steve Nye, et al, just reinforce, for me, this view. Thanks for another great piece, the VB. Always enjoyable reading…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love GTP album and want a 1mx1m Lego version of the album cover🙏🏼

Second version of GTP album cover less of an impact, due to DS famously photogenic imagery.

Taking Islands in Africa, literally takes me on a journey , amazing.

Having discovered Japan in the early 80’s then becoming obsessed. Trying to convert friends to this music was difficult, but the music of Japan has stood the test of time for me🙏🏼

LikeLiked by 1 person