Asked about the origins of his interest in shamanism in a 1986 interview, David Sylvian responded, ‘I’m not sure, I can’t really remember. I was reading a great deal on different cults and spiritual groups and so on, and the word shaman kept cropping up. And I bought one book – The Shaman Magician or something like that – and that really introduced me to that idea.’

The volume that piqued his interest was most likely The Shaman and the Magician by Nevill Drury, which was published in 1982 and carried the subtitle ‘Journeys between the worlds.’ In the book’s opening chapter – ‘The World of the Shaman’ – the author traces the traditions of far-flung tribes, from the Jivaro of Peru and Ecuador to the Mazatec Indians of Mexico, the Evenks of Siberia, and shamanic figures in Eskimo culture and that of Japan, Pakistan and Indonesia.

‘True shamanism is characterised by access to other realms of consciousness,’ Drury summarises, then quoting an earlier source: ‘The shaman specialises in a trance during which his soul is believed to leave his body and ascend to the sky or descend into the underworld.’

Across ancient practices that developed independently of one another in the farthest reaches of the globe there are many parallels that can be considered ‘typical of shamanism.’ For instance: ‘He is in a state of psychic dissociation caused by his near death; he gains visionary powers from the beings he encounters; he journeys upon a magic mountain [or] …in other cultures…the Cosmic Tree, and eventually arrives at the “centre of the world”; his enlightenment includes a vision of the world’s origin; vistas of serene and majestic landscapes, and imposing temples. Despite…traumatic encounters with powerful cosmic forces he is finally a transformed and “reborn” figure.’

The shaman’s experience and insight afford them a revered place in society. ‘In the sense that the shaman acts as an intermediary between the sacred and profane worlds, between mankind and the realm of gods and spirits, he has special access to a defined cosmos.’ And through this connection with this other world the holy man (or woman) can gain insight that is of benefit to the community, for instance in bringing remedies for illness. ‘Invariably the shamanic process entails direct contact and rapport with the gods and goddesses who provide their followers with first principles, with a sense of causality, balance, order and with it health and well-being.’

So did Sylvian have a desire to experience such things first hand, to participate even? ‘[Shamanism is] really a metaphor for me,’ he explained. ‘No, I don’t practice it. Of course I’m interested in the people that have in the past and the cultures and so on.

‘It’s really a metaphor for the individual as shaman, that you no longer need the second or third person. You don’t need somebody outside of yourself to instruct you as to who you are. You are in effect your own priest, your own shaman, your own whatever. You can connect yourself to the God-head or the spiritual self or all the rest of it.

‘Gone is the idea, I think, that you need these formal religions and these teachers, of one kind or another, that give you guidelines, very very loose guidelines, as to how to achieve that. I do believe there are some masters and some great spiritual teachers that have existed and continue to exist, and that is beneficial to be in contact with these. But on a much broader basis, the idea of formal religion and the kind of dogma that goes with that, I think, is dying, and should be.

‘We are perfectly capable, now, of making this contact without any sense of guilt, shame or fear. It’s possible. The idea of the shaman is just a metaphor for me for this kind of new age, this new way of looking at this inner connectedness.’ (1991)

The music on Words with the Shaman has always taken me to a scene in sub-Saharan Africa, a village gathered to witness the shaman’s ritual as he communes with another world. After the luminescent guitar in the opening of ‘Awakening’ – seemingly recorded at slow tempo and then sped up, raising the pitch and quickening each note’s decay – come the hypnotising rhythms that in my mind’s eye signal the shaman’s dance as he abandons himself to the repetitive beats, losing touch with one reality as he makes contact with another.

Drury’s second chapter examines ‘Shamanic Trance’. ‘Methods of trance inducement,’ he says, ‘…are an integral part of the shaman’s journey towards self-transformation…

‘The shaman’s drum deserves special mention. On a physical level, its rim is invariably made of the wood from the world tree…and its skin is directly linked with the animal the shaman rides into the underworld…In many shamanic cultures the drum is the steed and the monotonous rhythm which emanates from it is suggestive of the galloping of a horse on a journey.

‘On a contemplative level the sound of the drum thus acts as a focusing device for the shaman. It creates an atmosphere of concentration and resolve, enabling him to sink deep into a trance as he shifts his attention to the inner journey of the spirit. Erika Bourguignon notes that “drums, dance, etc., shut out mundane matters and help the individual concentrate on what is expected of him or her”.’

Close listening to the rhythmic section of ‘Awakening’ reveals different sounds emerging in the mix and then giving way to others. There is continuity in the pulse and tempo, yet the different sounds employ slightly varying patterns, occupying different beats in what is a complex and compelling movement. There is a musical as well as a spiritual inspiration at play here, with Sylvian admitting that ‘Reich is obviously present in the mix.’ (2004)

Listen to Steve Reich’s Drumming (1970-71) – especially ‘Part 2’ – or Music for 18 Musicians (1974-76) and you will hear something of the inspiration for the final part of Words with Shaman. Reich’s so-called minimalist creations often employ repeating patterns that subtly mutate or move slowly out of phase with one another.

‘In the summer of 1970, I travelled to Ghana to study drumming first-hand,’ explained Reich. ‘While there I took daily lessons from Ghanaian master drummers, particularly from the Ewe people, recorded them, transcribed the patterns and their relationships into Western notation and eventually they were published.

‘When I returned home, the effect of my visit turned out to be confirmation of gradually shifting phase relations between identical repeating patterns,’ this having been a concept explored in two earlier pieces employing ground-breaking work with tape loops, ‘…but now with strong encouragement to develop these ideas further by returning to my own background in percussion. Additionally, I had learned that complex rhythmic counterpoint had a long history in Africa…’

Drumming, Reich shares, is ‘divided into four parts that are performed without pause. The first part is for four pairs of tuned bongo drums, stand-mounted and played with sticks; the second, for three marimbas played by nine players together with two women’s voices; the third, for three glockenspiels played by four players together with whistling and piccolo; and the fourth section is for all these instruments and voices combined.

‘In the context of my own music, Drumming is the final expansion and refinement of the phasing process, as well as the first use of four new techniques: (1) the process of gradually substituting beats for rests (or rests for beats); (2) the gradual changing of timbre while rhythm and pitch remain constant; (3) the simultaneous combination of instruments of different timbre; and (4) the use of the human voice to become part of the musical ensemble by imitating the exact sound of the instruments.’

It seems to me that Sylvian was experimenting with ideas akin to some of these for ‘Awakening’. It is without doubt that the marimbas of Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians were already familiar. Steve Jansen has said that by the time of the sessions for Japan’s Gentlemen Take Polaroids he already owned ‘a few Steve Reich albums’ (2016). And during an online listening party for …Polaroids in 2021 he said of ‘Methods of Dance’: ‘Music for 18 Musicians featured a lot on my turntable at this time. It inspired trying out the marimba on this track. The repetition was created with repeat effects and double tracking.’ Jansen shares a writing credit with Sylvian and Hassell for ‘Awakening’ and here again the marimba sound is to the fore, albeit likely keyboard-generated on this occasion.

This was a case of a musical reference point providing the perfect framework for the subject at hand. As Nevill Drury’s book records, ‘It appears that monotony is the basis of many forms of shamanism: monotonous song, drumming, music dance with rhythmic movements.’

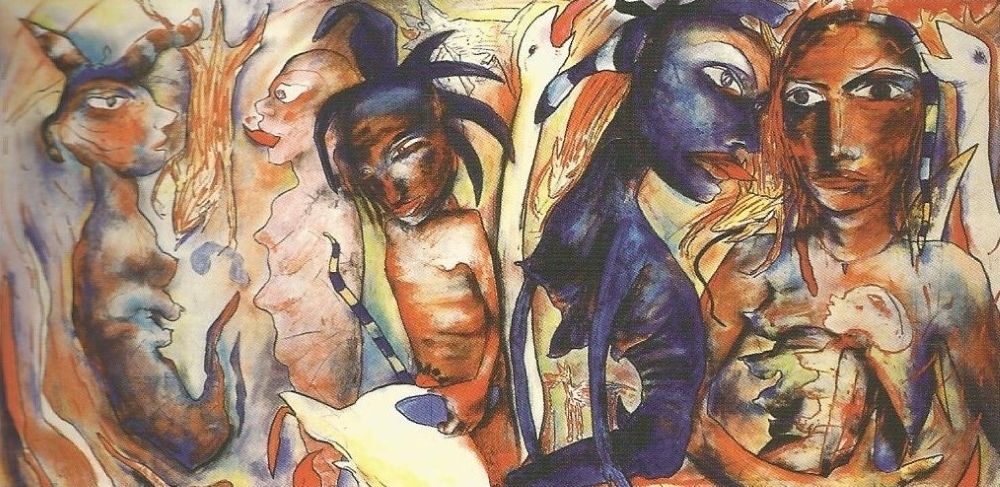

For the sleeve of the Words with the Shaman 12″ vinyl Sylvian chose a painting by British artist Amanda Faulkner, a detail from which was used for the cover of the cassette Alchemy – An Index of Possibilities and the expanded version in the later Weatherbox retrospective set. Faulkner had recently held solo shows at Woodlands Art Gallery in Blackheath, London (1983) and at the Angela Flowers Gallery, London (1985). There is something primeval about the canvas, rich with images of exotic headwear, contorted naked bodies and mysterious serpents. It’s a window into the imagined sound world of the music, heightening the viewer’s senses. Sylvian purchased the original painting: ‘I love her work. The vibrancy. The colours.’

I know I’m not alone in considering Words with the Shaman to be one of David Sylvian’s finest recorded works. Each element in the music and the presentation works together to manifest an atmosphere that evokes his vision. ‘I think that the best musicians respond to mood in music very well. I think most of… all of the people I work with, I would say, understand atmosphere. And respond very well to it. So I never feel out of my depth. Although I quite possibly am…’

Responding to an observation that the music of many of his collaborators has an air of melancholy or nostalgia, Sylvian reflected, ‘I enjoy that in music, and it always seems to be a sign – especially when I meet the people that created the music – a sign that somebody is always searching within themselves.

‘They tend to be very introspective people. I think that’s why I get on with them quite well. Because I’m very much that way. I spend a lot of time alone, and I spend a lot of time thinking about the spiritual nature of things, which I think is essential, especially in the kind of music I’m producing. It’s essential in any person, but it’s essential in creating the kind of music I’m creating, essential in people that come into the studio to work with me, that they can respond to that. It’s a kind of unspoken thing with a lot of musicians I work with. But it’s very important to me to feel that from music.

‘I think music…enables the listener to reflect upon themselves. Most good art does that, I think. Or maybe that is the definition of art, that it does turn you in on yourself and you look at yourself in a certain way that maybe you hadn’t done before. It puts you in contact with a part of yourself that you are not normally in contact with, or you are not aware that you are in contact with…

‘At the moment I’m very interested in the …Shaman piece that I did because when I finished it, again, I wasn’t sure if I’d done the right thing by doing that piece. But I listened to it again recently – I was in the car, travelling in fact – and it actually did what I… MORE than I expected it to do, in that it created the kind of magical essence in the environment I was sitting in – which was in a car, in a traffic jam.

‘And I was really amazed, I was taken aback that I’d done it. It was what I’d planned to do, but I didn’t know that I’d even got close to. And to find out that it actually worked to a certain extent, I was very pleased with in something. So now I’m geared up to try and follow that through. Which is probably again why I’m thinking of instrumental music, because I think that that lends itself to that purpose easier than a vocal album would.’

Joseph Beuys was a significant influence on Sylvian around this time and the German’s concept of the artist as a ‘modern shaman in society’ was a fascination (see ‘The Healing Place’). Beuys sought to use items from the surroundings of normal life in his work and to embue them new significance. Sylvian: ‘It appealed to me, the idea to re-form ties between the material and the spiritual, to try and make people that much more aware of everyday things around them. And relate to them in a different way – in a magical sense. I think that’s where the piece [Words with the Shaman] came from – to try and do that. As I said anyway to make people more spiritually aware of themselves and the environment they live in…

‘The titles of the tracks lend them themselves to very definite pictures – in my mind anyway – of the native shaman working in his native environment. To me that’s what the music conjures up in pictures. But I think it does more than that in a personal sense. The idea of yourself as the shaman. That there is no intermediary between you and the spirit world. You are one with it and you are the shaman. So it’s like “words with your inner self.” For me that’s what the concept of the piece was. But image-wise it conjures up more primitive images, I think.’

‘The goal was to inhabit the world of spiritual initiation and to try and reflect that musically by drawing on a wide variety of influences. It was an immersion into the ritualised, the repetitious and the exotic. It was also a continuation of themes explored on Brilliant Trees that I’d wanted to take that step further.’ (2004)

Words with the Shaman took up from Brilliant Trees not only in the music and contributing artists but also in the symbolism. The ‘cosmic tree’ or ‘world tree’ was part of shamanic tradition. ‘The symbolic Tree,’ Nevill Drury observes, ‘is a vital pillar in the cosmology for it connects the three planes of reality. The crown of the Tree reaches into the heavens, the trunk sustains the middle world and the roots extend down into the underworld.’ The trance-like rhythms of ‘Awakening’ coupled with the transcendent improvisations of Jon Hassell lift the listener to a spiritual world which finds its voice in ‘Songs from the Tree Tops’.

Words with the Shaman

‘Part 3 – Awakening (Songs from the Tree Tops)’

Holger Czukay – radio, dictaphone; Jon Hassell – trumpet; Steve Jansen – drums, percussion, additional keyboards; Percy Jones – fretless bass; David Sylvian – keyboards, guitars, tapes

Music by David Sylvian, Jon Hassell & Steve Jansen

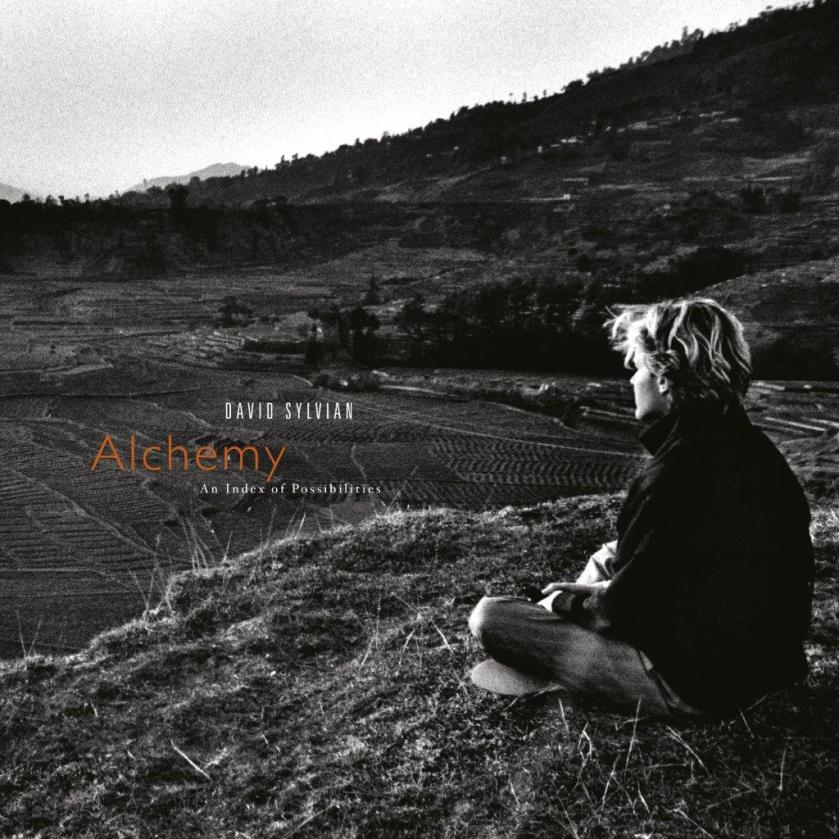

Produced by David Sylvian and Nigel Walker, from Alchemy – An Index of Possibilities, Virgin, 1985

Recorded in London, 1985

‘Awakening (Songs from the Tree Tops)’ – official YouTube link. It is highly recommended to listen to this music via physical media or lossless digital file. If you are able to, please support the artists by purchasing rather than streaming music.

All David Sylvian quotes in this article are from 1986 unless otherwise indicated. Full sources and acknowledgments can be found here.

Download links: ‘Awakening (Songs from the Tree Tops)’ (Apple); ‘Drumming – Part 2’ (Apple)

Physical media links: Alchemy (Amazon – vinyl re-issue); Drumming (Amazon)

‘I find instrumentals rather intriguing to do. They are so enjoyable as the kind of technique is so different.’ David Sylvian, 1987

More about Alchemy – An Index of Possibilities:

Words with the Shaman

Ancient Evening – Incantation

Preparations for a Journey

Steel Cathedrals