In the liner notes to his 1989 Sound and Vision retrospective collection, David Bowie recalls how ‘one day in Berlin, Eno came running in and said, “I have heard the sound of the future.” And I said, “Come on, we’re supposed to be doing it right now.” He said, “No, listen to this,” and he puts on ‘I Feel Love’ by Donna Summer. Eno had gone bonkers over it, absolutely bonkers. He said, “This is it, look no further. This single is going to change the sound of club music for the next fifteen years.” Which was more or less right.’

‘I Feel Love’ was released on 7″ in the summer of 1977, a cut from Donna Summer’s album I Remember Yesterday. The LP’s concept was to combine electronic disco sounds with the styles of bygone decades, with the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s referenced on side one of the vinyl. ‘I Feel Love’ closed side two and was conceived by the producers Pete Bellotte and Giorgio Moroder – who also co-wrote the track with Summer – to represent music from a time to come.

‘I definitely wanted to explore it as a whole concept and come up with a sound that was of the future,’ said Moroder in a 2015 interview with the Library of Congress. ‘I did it by only using synthesisers, because I thought it was the instrument that would be used in the future – be the instrument of the future. We used it, and only it, to create all the sounds. I wanted to try to imitate what people would do in 20 or 30 years.

‘I used all digital sounds for the song, all of them coming from the computer. Everything except the voice was created by the Moog…I had to start with the tracks not the melody. So, I started with a bass line. It was a big, big job.’ Using what was immature technology caused significant challenges, not least because the equipment refused to hold its pitch: ‘The problem then is I had to stop and restart after every seven to eight seconds to retune the synth.’

The electronic sounds provide both a seductive gliding effect and an insistent, spiralling propulsion that was unlike anything that had gone before, the precision and perseverance of its delivery beyond the dexterity of the most accomplished keyboard player. Subjecting the synth output to further effects was part of the alchemy. ‘While we were mixing it,’ Moroder recalled, ‘my engineer added a delay and it gave it a whole new feel and that’s what’s really what made the sound; it’s what made that driving bass line.’

Compare the track with the previous Moroder-Summer collaboration ‘Love to Love You Baby’ and it is evident that disco music was transforming into something new, a genre that would become known as hi-NRG. The single topped the charts in the UK while reaching number 6 in the US Billboard Hot 100. ‘I think it was the contrast between the metallic, drum machine, that sound, and then the beautiful romantic voice of Donna,’ reflected Moroder. ‘Based upon the music, you would expect a robot to be singing, not Donna! It was a “Beauty and the Beast” type of thing. It was a whole new dimension that you wouldn’t expect.’

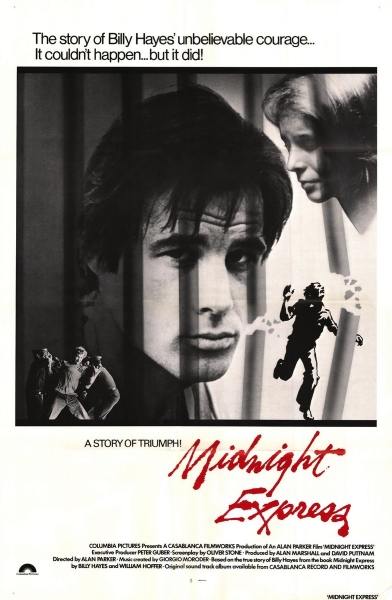

The song’s success would open up new opportunities for the producer. ‘You know the soundtrack to the movie Midnight Express was based upon ‘I Feel Love’,’ he said. ‘The director Alan Parker loved the song and he wanted me to record something in that style for a very dramatic scene in the movie—the chase scene. He wanted it to have that driving bass line. So that film really opened up the idea of electronic music in movies. I think it was the first to all be done with electronics.’

Once again, the result was an overwhelming success with Moroder awarded an Oscar for best original score at the Academy Awards in 1979. It was the film soundtrack that would play a part in linking Giorgio with a young English band who were struggling to gather enough of a following to justify their record deal. It also helped that their label, Hansa, was much more familiar with dance music than Japan’s brand of US-influenced rock as evidenced on their first two releases, Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives, and had an established professional relationship with Moroder.

‘It had been suggested by Simon [Napier- Bell, Japan’s manager] that we consider working with a famous producer, someone who had his own distinctive sound and could leave a mark,’ recalled Mick Karn.

‘After seeing Midnight Express, Dave thought it might be interesting to work with the composer of the soundtrack who was also a producer. Ariola Hansa loved the idea, Giorgio Moroder was the producer who had brought disco to the world via Germany with some of their very own artists. We liked the idea too, it would surprise the public and the press alike, and hopefully help to get rid of the heavy metal tag that was still following us from write-up to review.’ (2009)

The band were still grappling with the challenge of finding an artistic voice of their own. ‘I think we were ready to move into an area of music that was more electronically based, and at the time I’m not sure whether it was management or the record company that was pushing Moroder,’ said David Sylvian. There was also another positive reference point to confirm that it was an opportunity worth pursuing. ‘He had just produced an album for Sparks which we thought was interesting, so we thought we’d give it a go.’ (2001)

No1 in Heaven was released in March 1979 and saw the established duo of Ron and Russell Mael move away from a more traditional rock band set up of guitar, bass and piano in favour of the electronic synthesis of Moroder’s sound, with tracks such as ‘Tryouts for the Human Race’ melding the sequencers of the ‘I Feel Love’ disco vibe with their own pop song-writing.

‘We were all fans of the Midnight Express film and soundtrack, which had just won Giorgio Moroder an Oscar, so the notion of flying to LA to record with him was an exciting one,’ explained Rob Dean. ‘I personally also really liked the work he had been doing with Donna Summer too. Combined with the heavy presence of Kraftwerk and YMO in our album collections, it felt like the next logical step and we were banking on it causing us to break through in the pop market, which if we were to stay with our current record company, Hansa, we would need to do.

‘So we flew over for about five days staying at the Beverly Hilton, no less.’

‘Chase’ had been lifted as a single from the Midnight Express score. ‘It was the propulsive repetition that appealed,’ said Sylvian, ‘which also related to a burgeoning interest of my own in this broad field of development: Kraftwerk, dub music, Steve Reich and the so-called minimalists.’ Here was an opportunity to achieve ‘a shift in my compositional evolution that might propel me away from the band’s determinedly rock-based orientation.’

Japan’s lead singer arrived on the West Coast a few days before the rest of the band, travelling immediately after the euphoria of the band’s first live shows in the country from whom they took their name. Once the others joined him, they would all note the resemblance of the disco maestro to Peter Sellars’ characterisation of Inspector Clouseau in the Pink Panther movies. ‘That’s who he used to remind us of, Clouseau,’ said Sylvian. ‘He was this kind of funny, little, slightly bungling character. It was an odd little experience, and I just think it set the ground for Quiet Life. It was almost like being a songwriter for hire. It was one of those experiences: “we’ll throw you into a studio in LA with Moroder,” and he dishes out some old demo from his stack and says, “Try working with this,” and it’s like “Okay.” It was odd but not unpleasant.’ (2001)

Simon Napier-Bell remembers travelling with Sylvian before the others joined them. ‘We arrived and had a meeting with Giorgio who played us a selection of songs he’d written and asked David to choose one. To Giorgio’s surprise, David chose what was obviously the weakest of the bunch. “Why, for heaven’s sake,” I asked once we were outside. “Because,” he explained, “it’s such a poor song Giorgio won’t mind if I re-write it. Whereas all the others are pretty good, which means I’d have a hard job injecting myself into them.”

‘David was nothing if not shrewd. And he couldn’t have been more right. He re-wrote the song and called it ‘Life in Tokyo’. Giorgio didn’t even blink.’ (2024)

Rob Dean: ‘The song started life as an idea on a cassette that Giorgio had thought of using for the Jodie Foster movie Foxes, which David had fashioned quickly into a song.’

The movie Foxes premiered in 1980 and perhaps Moroder had been gathering material for the soundtrack, with this demo discarded or diverted for the project with Japan. Some have reported that the composition was originally intended to have a vocal by Cher in the film, who did indeed sing on another track for Foxes. The demo tape is a fascinating listen. A basic introduction and the chord sequence underpinning the verses of ‘Life in Tokyo’ are recognisable but the track veers off in an entirely different direction as it develops. If you started to listen half-way through you’d never guess that this was the starting point of Japan’s subsequent release. Apparently, Moroder also provided a version of the demo complete with a possible vocal line.

Rob Dean remembers how the recording was approached at Rusk Sound Studios in the heart of Hollywood: ‘In the studio, Giorgio had a drumkit set-up with “his” sound and in fact it was a very controlled recording environment, leaving little to error.

‘For his trademark sequencer sound, he brought in Harold Faltermeyer who at the time was his keyboard programmer. Harold laid down the part by playing it manually with a slap delay of equal volume which I think surprised us all, as we presumed it would be an actual sequencer but that human element was actually at the core of Giorgio’s sound. He also had his trio of backing singers who had appeared on all the Donna Summer hits, amongst others.’

Ironically it was the artificially generated sequencer sound that was one of the strong attractions of the collaboration for the band. ‘I always wondered why they didn’t use a sequencer,’ mused Richard Barbieri. ‘It’s obviously a step sequencer on ‘I Feel Love’ and the Midnight Express soundtrack.’

Back to Rob Dean: ‘The sessions went so quickly that all, or at least most, of the instrumental parts were finished in a single day. The next day was left for final vocal and mixing. It was enjoyable, but there was no mistaking who was in control and the efficiency on display made it feel more like a demo session really.

‘Had the single been a hit, then I suppose it could have been possible that Giorgio would have been asked to produce the album. Had that been the case, Quiet Life would have been a very different beast.’

There has been a persistent rumour over the years that the original intention was for the band to record their own track ‘European Son’ with Moroder, only for this to be substituted with something on which the Italian could share a writing credit. This is, however, dismissed by Sylvian. ‘I don’t recall the song being presented to Moroder as an option. I did have it kicking around, we may even have been performing it live. I possibly had it in my back pocket to fall back on.’

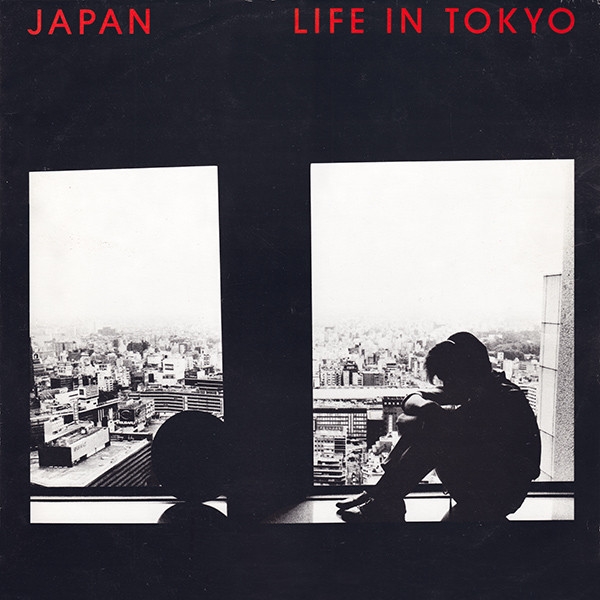

The single was completed in a couple of days and rushed into production, hitting the stores in April 1979, the UK edition in an attractive red vinyl. Looking at the video now, it seems much more dated than the music itself, and it’s almost incomprehensible that by late 1981 the band would have released three more albums – Quiet Life, Gentlemen Take Polaroids and Tin Drum – whilst completely transforming both their musical style and their image.

‘Life in Tokyo’ promotional video

Similar to the treatment afforded to Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’, the 12″ version of ‘Life in Tokyo’ was significantly extended with the dancefloor in mind. The long version shows off how Sylvian had expertly devised a verse over the ‘Foxes’ chord-skeleton and added an ear-worm chorus whose words were inspired by a head full of images and experiences from the culture shock of his first brush with the land of the rising sun. Punctuating the arpeggiated synthesisers was a perfectly judged saxophone barrage.

‘They’re only buildings and houses

Why should I care?

Oh, life can be cruel

Life in Tokyo’

Unfortunately, no great impression was made on the buying public and the desired chart-placing remained elusive.

Some have credited Moroder with accelerating the band’s change in sound towards Quiet Life but Richard Barbieri is clear that the evolution was already underway and that the band followed their own vision. ‘Well I think the sound was there anyway. The sounds were changing and a lot of people were using sequencers – that was the basis for the Moroder sound from Donna Summer and the like. I think we took that further with the Quiet Life album, we used sequencers but we were incorporating orchestras and all kinds of sonic elements into it, and I think we really made a mature album with Quiet Life.’

‘Life in Tokyo’ would next resurface in 1981 as a re-release by Hansa after the band had moved on to Virgin and were just putting out new material in the shape of ‘The Art of Parties’ single in the gap between Gentlemen Take Polaroids and Tin Drum. The timing was infuriating with two Japan singles released within days of one another and effectively competing for both radio play and sales. This time the song was backed with ‘European Son’ which the band had completed as their own slice of electro-pop without Moroder’s help. Again, the charts were left untroubled.

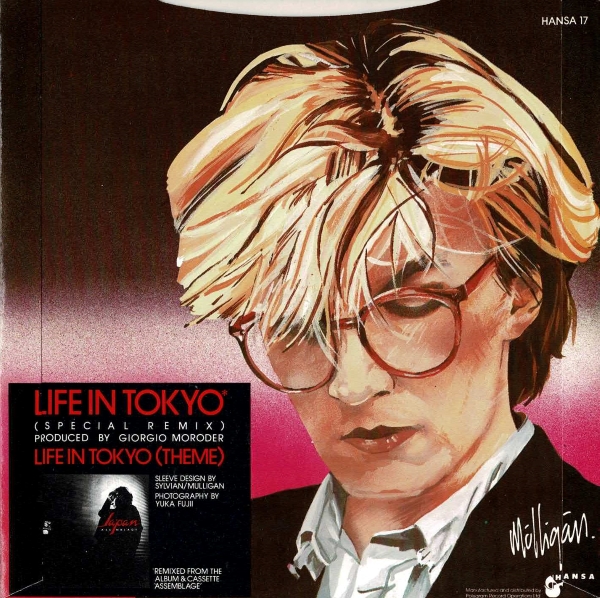

Japan did finally win favour in the UK with the critical and popular acclaim of their final album, Tin Drum, leading to a spate of releases from across their catalogue. A unique mix of ‘Life in Tokyo’ was included on a special double-play cassette edition of Hansa’s Japan compilation album, Assemblage. Here prominent synth lines are added that date back to the initial sessions but didn’t make the original mix, together with synthetic crack-of-the whip percussion which is very much ‘of its time’. All traces of saxophone are erased.

The song would finally achieve a measure of chart success with yet another re-release, which this time the band oversaw, going back into the studio with Tin Drum producer Steve Nye to remix the track and over-dub some new elements. This was a chance to put right something with which Mick Karn had never been satisfied. He remembered the LA sessions as ‘an interesting and educational experience, but personally, I was very unhappy with ‘Life in Tokyo’, after I came up with several bass lines, all of which I was told were not right. I felt betrayed by the others, who kept taking Giorgio’s side and moving me further and further away from my own style of playing and into what I can only describe as a simple country and western bass pattern that any bassist could have written. It just wasn’t me, a case of too many cooks. There are only two distinctive elements that separate ‘Life in Tokyo’ from any other work by Giorgio Moroder, Dave’s vocal and the saxophones. It could all have been so much more original if the musical balance had shifted slightly more in our favour rather than Giorgio’s.’ (2009)

For this 1982 single release, Karn re-recorded the bass part in his much more familiar fretless styling from the band’s more recent work. It meant that the record now sounded much more akin to the live version that the band would continue to perform throughout their valedictory Sons of Pioneers tour in the final three months of that year. It’s also been reported that the additional studio time was also an opportunity for Mick to lay down new saxophone parts for the song. The resulting single peaked at No 28 in the UK.

Whilst there are only three core vocal versions of ‘Life in Tokyo’ – the ’79 original, the ’82 Assemblage cassette version and the ’82 Steve Nye re-working – there are a dizzying number of edits and mixes derived from these. A further curiosity is the existence of ‘Life in Tokyo (Theme)’ which appeared mixed by Steve Nye as a b-side on the ’82 single and also exists in an original Moroder mix from 1979. A significantly slowed down instrumental rendition, it bizarrely played at something near normal speed if your turntable had the facility to play at 78 rpm. A version of the Nye ‘Theme’ at ‘correct pitch’ was included on a cd containing nine variations of ‘Life in Tokyo’ that was bundled with some formats of the deluxe boxset re-release of Quiet Life in 2021.

Whether you enjoy the song or see it as light-weight juvenilia, seeing Japan collaborate with an acknowledged pioneer of electronic music and contemporary Oscar winner creates a fascinating episode in the development of the just-21-year-old Sylvian’s song-craft and the evolution of the band. Certainly some were listening carefully and it was a case of the band influencing their influencers as members of YMO subsequently acknowledged that the 12″ version of ‘Life in Tokyo’ fascinated them greatly, with Japan absorbing elements of disco but taking them to a new place.

The band-member’s reflections, however, aren’t totally positive. ‘Working with Moroder was a whole lot of compromise,’ said Steve Jansen. ‘That project, as well as ‘I Second The Emotion’, were business decisions and were musically much more conventional than we would normally want to be, purely for the purposes of appealing to a wider audience.’ The time at Rusk Sound Studios in LA amounted to a ‘rather boring session,’ he added, ‘though it was no one’s fault. We were all on a mission to get the thing done in a matter of hours.’ Jansen’s conclusion: ‘I don’t like the track at all.’

Richard Barbieri: ‘The idea to work with Moroder was that the record label wanted us to have a hit. So I think it was, “Look you need to have a hit record, go to this guy, he’s the one who will get you a hit record.”…And working with him, I don’t know, it was pretty sterile, I’d say. I mean he basically sat there and another guy did all the work but he had the vision and the ideas. It was just that kind of sequencer driven thing with the four to the floor and then crafting a song on the top.

‘And I think we were his only non-hit record, possibly! It kind of didn’t work – but became a cult classic, was played in all the clubs.’

‘Life in Tokyo’

Richard Barbieri – synthesisers, keyboards; Rob Dean – guitars; Steve Jansen – drums, percussion; Mick Karn – bass, saxophones; David Sylvian – vocals, occasional guitar

featuring Harold Faltermeyer

Music by David Sylvian & Giorgio Moroder. Lyrics by David Sylvian.

Produced by Giorgio Moroder, released as a single by Hansa, 1979

Subsequently remixed by Steve Nye, 1982

lyrics © copyright samadhisound publishing

‘Life in Tokyo – Steve Nye 12″ remix version 1982’ – official YouTube link. It is highly recommended to listen to this music via physical media or lossless digital file. If you are able to, please support the artists by purchasing rather than streaming music.

All artist quotes are from interviews 2017-2023 unless specified. My thanks to Michael Higgins for the images and brief audio excerpts from the demo cassette. Full sources and acknowledgements for this article can be found here.

Download links: ‘Life in Tokyo’ (original 1979 12″ version)’ (Apple); ‘Chase’ (Apple); ‘Life in Tokyo (Theme)’ (Apple); ‘Life in Tokyo’ (Steve Nye 12″ remix 1982) (Apple)

Physical media links: Quiet Life (2021 reissue boxset) (BMG) (burningshed); Midnight Express (Amazon)

‘It was the next step after Obscure Alternatives. Giorgio’s style was very different from what we’d been used to. He used a specific studio, set the drum kit up a specific way, used his specific backing singers, used his specific keyboard programmer, who’d programme and play the sequencer parts. It was the same set up Giorgio would use for Donna Summer or anyone else, a very regimented way of working. It was so quick and efficiently done…I enjoyed the experience as a one-off, but I don’t think it would have worked for an album.’ Rob Dean, 2021

More about Japan 1979/1980:

In Vogue

The Other Side of Life

Nightporter

Taking Islands in Africa

Thank you, thevistablogger, this is totally part of ‘my bag’. I don’t mean (just) the Moroder input, which was undeniably great, for the track highlighted. As well as this work for Japan, he worked with others whom I’m particularly fond of/’into’, such as Sparks (we saw/heard, the opening date of their last World Tour…they’re still running!) and Phil Oakey/The Human League, et al, as you’ve picked up, in another informative article. Each time, in my view, the different collaborations worked.

Rob Dean has made some great comments, captured by you too, which I think very perceptive (but he knows better than I anyway, as an integral part of the band at the time).

I’m also happy that David (Sylvian) has a collaboration of his own with Isabelle Adjani (in so far as within one track on her album) coming out on 10 November 2023 (with others I also know of, Seal, Le Bon et al). This is exciting.

Japan, never say, never again. I don’t think any of you have (?) though stand to be corrected by anyone with greater knowledge of the topic. At some future point, collectively, former surviving members might think it right, or might not, but people, including me, would certainly come out to see and hear them. Mick (Karn) can never be replaced (as, in my view, one of the best three bass players EVER, with a totally unique style of playing) but, he probably would be happy for his fellow members to take the band out again (I’ve seen a few of the comments by some of those that met him).

I’ve been to five gigs myself in the last thirteen months (at 63 / 64) and I’ve another five to see and hear between now and May 2024, so the (older) audience is definitely there and (still) hungry. My best wishes to all…

LikeLike

Hi, thank you again for the interesting insights although Life in Tokyo was never one of my favourite Japan Tracks. But Giorgio Moroder is not German ( you wrote: ….with something on which the German could share a writing credit…)!

He was born in South Tyrol which is part of Italy. Best, Thomas

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course! I will correct this at the first opportunity. My apologies.

LikeLike

It‘s even more complicated. „Technically“ a person born in South Tyrol is an Italian. But If you would ask this person he/she would say „I‘m South Tyrolean“.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A small, nitpicky point. The edition of Assemblage mentioned was not a double cassette (suggesting two tapes), but an double-length cassette featuring the full album on side A, with the remixes on side B (which turned out to be the version of the LP released by Victor in Japan).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, thanks. I should have said double-play cassette.

LikeLike

Good morning, I have additional comment on the track. Most (Japan/Sylvian) fans will have seen the YouTube footage of the ‘final gig’ (1982). Wasn’t it the last track Japan ever played live? David and Mick, looked really happy. Moreover, the joy of the players collectively, made me smile. The Japanese crowd loved it. Unless I’m mistaken, John Punter also joined in (the vocal). The fact that the track ‘only’ made No. 28 in the UK, hardly reflects the global reception of the work. It may have been something of a bridge into the success that followed the track. Admittedly, the first tracks I bought (as singles) were Quiet Life and European Son.

One other thing within the VB article, that I hadn’t initially appreciated, was that Japan squeezed three albums into what seemed an incredibly short time frame, for work so melodious/accomplished, and this may have become a burden, on David particularly, and may have contributed to the decision to break up. The demo included in the feature, shows what can emerge from the few chords of a short backing track idea (with the application of a talented composer collaborator). The song remains and has the final ‘say’, so it should be…

LikeLiked by 1 person