‘I’ve been slightly afraid,’ revealed Lucrecia Dalt as her album A Danger to Ourselves was released after months of intricate crafting and then the best part of a year taken up with the practical machinations required for its public launch. ‘I say afraid because I recognise it as a fear to expose the personal in music. I’ve always been somewhat reluctant to do it, so it felt more comfortable to invent a whole story that I could talk about, so I could detach emotionally and create something based on that. But in this one it felt for the first time, very naturally, like I wanted to work from the process of pretty raw sincerity.’

The previous album, ¡Ay!, had been an adventure in what Dalt dubbed ‘Bolero sci-fi’ (2024). ‘The lush musical world of ¡Ay! offers a soft but obscure landing for an alien entity called Preta,’ read the launch announcement, ‘who has gathered a body in the hydrosphere from evaporated dead skin. We follow her first experiences of containment and composure as she navigates our geology and earthly markers of love and time, in contrast with her state as a timeless entity.’ The record prior to that, No Era Sólida, had seen Dalt directed by the impulses of a second self, Lia. But for A Danger to Ourselves there would be no fantasy protagonists.

‘The lyrics function as declarations, or odes, and the most personal truths I have explored to date are found within those lines,’ she said in an interview to mark the release. ‘The whole musical part happened in New Mexico, but prior to that I was travelling quite a bit, I was ending my tour for ¡Ay!, the previous album, and I guess in that moment I started to manifest the first thoughts and ideas.’ In particular, Dalt’s connection with David Sylvian was deepening and being expressed through long distance correspondence as her extensive tour rolled from country to country. ‘It was the starting of a relationship and that prompted a lot of ambitious wording.’

‘At the time, I was reading Sharon Olds’ Odes, which is a book of poetry that is bold and absolutely wonderful. For the first time, I started reading something so brutally honest, yet comedic and satirical at the same time. It was romantic, but not explicitly – and kind of a protest, delivered in your face…That was, like… damn, I really want to have that clarity.

‘That inspired me to start thinking about the way I was constructing certain texts and poems for my partner at the beginning of our relationship, and how I wanted to explore that feeling. It’s something you try to describe with words, and they sometimes fail, but you keep trying, and then something gains a little more coherence – and once it does, you’re like, oh, this could actually be content for an album. And then eventually you’re trying to create the soundscape, the soundtrack to those ideas and thoughts.’

Following the opening track, ‘Cosa Rara’ (of which more here) comes the album’s shortest song, ‘Amorcito Caradura’ (‘My love you’ve got a nerve’), and we know immediately that we are inhabiting a different space to previous projects. Lucrecia’s voice, an acoustic guitar and upright bass are to the fore; ‘this is like a haiku ranchera,’ she explained. The piece ‘happened as a joke. I didn’t know if I was going to include it.’ There is both humour and an honesty which is emphasised through the stripped-down arrangement and impassioned vocal. ‘Love oriented rancheras speak very directly to the lover, usually in brutal terms. I wanted to have my poetic take on that, so I sing:

‘Amorcito de mi vida

que to quiero

y que to quiero

¿por qué me

despistas tanto?

si de amor

yo me muero

Amorcito caradura

deslúmbrate

sin miedo

y ponme arena

en la garganta, ¡si!

¡que así canto

como usted señor!’’

‘My dearest love

that I love you, that I love you

why do you throw me off so much

if of love I die?

My love, my naughty little sweetheart,

don’t be afraid to be dazzled,

and put some sand in my throat, yes!

so I can sing like you, sir!’’

(all English lyric translations from the Japanese cd insert of A Danger to Ourselves)

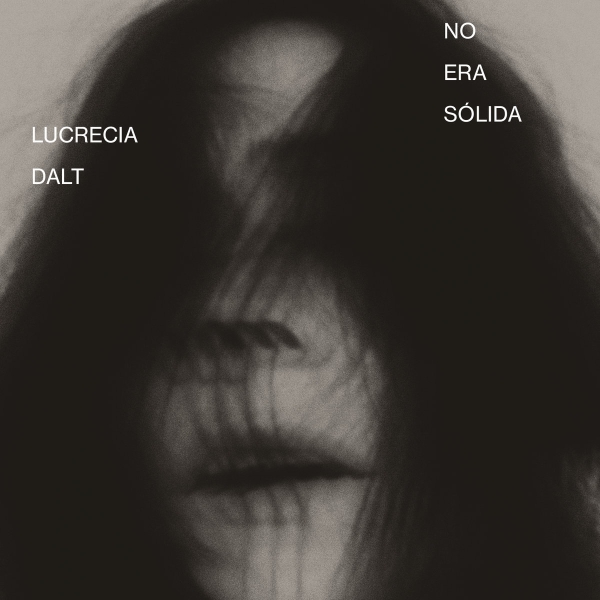

A veil has fallen – in a parallel, it seems to me, to the image selection for the album sleeve. The photograph of Dalt on the cover of No Era Sólida is indistinct and processed, just as her vocal is treated and twisted in the music. This time, Yuka Fujii’s shot is unadulterated, the artist laid bare and in focus. Yet there is still mystery in the expression – is that a tortured grimace or something else? It’s a marked contrast to the deadpan pose that most covers sport.

‘I’m more of a shy person. I like the contrast of that with a cover like this. It’s a very intimate gesture – a strong gesture, maybe ugly for some,’ Lucrecia explained. ‘There’s an implied way of being, of posing, of presenting yourself on instagram, and so on. And I wanted to challenge that: it’s like, I’m not going to do the poker face, this is ridiculous. I just want to present a gesture that is raw and bold, and that maybe no one has seen from me before. When you see it, it’s like, “Oh, what’s happening here?”…

‘I showed it to my family members, and they were like, “Ooooh, I don’t like it.” And I was like, “Okay, I’ll take it – it’s fine”.’ The slightly discomforting image matched the album’s title too. ‘At some point it was suggested and I started to feel like it made sense,’ she recalled. ‘I thought that in a way it was a sentence that somehow grabbed part of what the album is about.’

‘Even though the album has really intense explorations of love, surrender, transcendence, and so on, it also presents a certain danger. Behind that can be many, many expressions of frustration, but also satire and comedy.’

Whilst the lyrics are deeply personal, they are laden with cultural reference points, from Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart in ‘Cosa Rara’ to J.G. Ballard’s Crash in ‘Mala Sangre’. In the case of ‘Acéphale’, Lucrecia explained, ‘the name comes from a publication by George Bataille and is a metaphor for wanting to cut off your lover’s head because he’s overthinking.’ ‘The concept,’ she added, ‘comes from a poem I wrote to David, saying, “I want to cut your head so that you can stop thinking that much, and you connect more with your heart”.’

‘acéphale clueless mind

you thought too much

my wildest creature

your eyes

sapphires

Feet poised apart,

balance set

shoulders aligned,

in witful dissent

fire bend, katana held

the sword is the thought

the sword is the grace.’

It’s a track that displays the core musical structure of the album, constructed with the triple pillars of Lucrecia’s voice – slipping seamlessly across languages and between singing and spoken word, the innovative and complex rhythms of Alex Lázaro, and the deft and sensitive bass work of Cyrus Campbell. The upright acoustic and electric bass across A Danger to Ourselves is outstanding: playing at a good volume through decent speakers is a must. Dalt: ‘I was like, how much can I hold it without the usual elements that we are accustomed to: keyboard or guitar? Those are there but are kind of ornamental.’

Around this tripartite frame there are disparate meticulously placed sounds which coalesce to enhance the atmosphere and supplement the rhythms. The tremendous aural variety in these added elements makes it an absorbing listening experience: some sounds in the palette are long and smooth, others contorted, many are percussive. All somehow complement the songs, in some cases literally – for instance, ‘Acéphale’ has a sound like the unsheathing of a blade from its metal scabbard. Yet the mixes are never crowded. ‘I love to work on delicious depth enhancement,’ Lucrecia said. ‘I feel so connected to that way of working in which you allow time. You get absolutely obsessed and possessed by the work, and then things start to come out of that.’

These don’t sound like songs written on a piano or guitar and then deconstructed into sparse arrangements. ‘It’s hard to describe, but I guess the composition starts to emerge in parts and slowly starts to become a thing by spending enough time…And then obviously the voice is trying to keep a structure that is more common, to chorus and verses or whatever,’ confirmed Lucrecia. ‘I thought it would be nice to have the voice very present, work around percussion, and try to see if I could create music that hints at a structure that could be more pop, with very simple elements and then a lot of sound design. Just because I enjoy, so much, working on tiny details, working obsessively with sound.’

The second single released ahead of the album was in digital format only, but this time accompanied by a full track-length video. Introducing the song on the BBC Radio 6 show, Dream Time… with Zakia, Lucrecia explained, ‘It is about wanting to be possessed by your lover from within, to be pulled in by them until all there is, is lover. And it explores also the idea through the lens of Orpheus, about wanting to recover your lover from the underworld but kind of what you’re trying to do is to come to terms with your own self, with your own image. It’s called ‘Divina’ which means ‘Divine’.’

‘I always wanted to make a ballad like this! With those doo-wop type of vocals,’ she revealed. The lyrics betray ‘intimacy, where licking your lover’s tears is the purest devotional act. I say, “your ketamine tears”, as a metaphor for the dopamine high you get with a true lover.’ The opening frames of the video bring to life the thought that ‘if you lick the tears of your lover, you can basically have a trip – or the idea that you can possess the lover by swallowing them.’

‘I circle you

in cerulean blue

in this underworld

underworld

a ritualised fire

a plume of desire

hugging and burning

flesh blended

dying as “you”’

The album’s release material stated that the record emerged after ‘spending enough time in the abyssal realm of erotic delirium.’ What set this project apart from previous work, Dalt said, was ‘allowing yourself to be more literal about sensuality. I don’t feel like it was different in ¡Ay!. The sensuality is there, it’s just that the story was so alien and so not personal…Or maybe I was scared to put the alien in that space. For this one, it’s just not being afraid to expose your feelings, what you are experiencing at a moment in time…it felt right to explore it that way.’

A Danger to Ourselves ‘was made in a moment that is the flourishing of a relationship that has mystery in it. And so I was very inspired to write lyrics, and kind of put everything in, references I love about fictions, or ideas about consciousness that I’ve been thinking a lot about, but I tried to bring it to a place that felt more like very intimate in a relationship context, which I’ve never done.’

The way in which the various sound elements on ‘Divina’ are constructed and placed so precisely is a delight. There are no fripperies. ‘I feel that my strongest part is just the computer software, the processing of sound, compiling things and crafting from so many different sources. This is my process of creative validation – it’s not coming from virtuosity,’ said Dalt. ‘My music is not about being an expert of your craft but being intuitive and passionate and resourceful.’

‘For me it’s important to make a record that has sounds I don’t hear anywhere else. I have nothing against traditional music or traditional instruments, I love when someone can play a guitar gracefully and I admire that. But I feel my brain is more attuned to those little nuances and details and space. I think about, yeah, spaciousness, and I felt in a way the songs are trying to embed the elements that need to kind of honour those words…Sometimes it’s like the lyrics go this way, the music goes another way, but in the end they’re married.’

David Sylvian had a significant part to play, given he was entrusted with creating the final mix for the album. ‘His contribution became fundamental to A Danger to Ourselves. Because not only was he in the process when I had conceived the pieces – kind of like guidance, mentorship in a way – but also, once the album was ready, with all the elements, the drums, and so on, he mixed it, and he co-produced it in that way, because he’s a creative mixer. His way of mixing is to think creatively – maybe cutting something halfway through, processing a guitar totally differently than I proposed, and suggesting other things.’

‘On ‘Divina’ he took more liberties with distortion and panning. It enhanced all the little details I had produced that maybe you were not able to hear. I feel the processing and details on this album became more embedded, not like just one layer.’

This element of collaboration on the final sound of the album was another novel aspect of the project. ‘It’s very nice that you are directing the whole thing, that your vision is still there, but maybe one thing will surprise you. One effect David added, for example, to ‘El exceso según cs’, he added such a crazy effect at the end [‘bubbly delays that were so fantastic and so cool’], and then I started to love it. I was so thankful that he did come as more of a co-producer, in a sense, which is the first time that I had that. Up to that point, I’ve been the ultimate decision-maker. In this one, David was flowing a little bit more with me in that space. And I really like that.’

‘Some tracks were more finished…for other tracks, he proposed a little bit more of depth, detailing so that it becomes this more open thing. I love records in which dynamics are important.’

‘David feels safer when he’s left alone. Our version of sharing is listening to stuff together, discussing it. We share ideas, and then he goes to his space, which is his safest way to work. I feel fine with that, and I also feel fine working hands-on with someone in the room and which I do with Alex or Cyrus.’

Two of my favourite pieces on the album are ‘Hasta el Final’ (‘‘Til the End of Time’) and ‘Stelliformia’. I love the rhythms from which many of the album’s songs first sprang, but for these two tracks other elements are foremost, and Lucrecia’s voice truly shines. No doubt it’s the contrast within the running order that emphasises these pieces as moments of calm and deep reflection.

The opening of ‘Hasta el Final’ sounds like something that could have been lifted from Ryuichi Sakamoto’s poignant final album 12, released just two months before his passing and containing his final, sparse, musings on piano and analogue synth. ‘This is my favourite and most sentimental song on the record,’ admitted Lucrecia. ‘And the first time I write string arrangements for my own music.’ Accompanying the strings is something that sounds like the straining of cords carrying a great weight, as if at breaking point, and once again there is fine extempore double bass from Cyrus Campbell.

‘When you choose the right collaborators, you just don’t have to make any effort, and you can feel that immediately. I remember bringing sheet music to Cyrus, and I started to feel like he was vibing more with the intuitive process, which is better for me. When I started to feel that switch, I was like, “You don’t need this paper, right?” And he was like, “No, I don’t,” and then he started to be free. He started to be himself. He started to respond to what the song needed, and that’s the best thing.’

Hearing the nuance and clarity of the vocal delivery, it’s difficult to believe that it’s an aspect of Lucrecia’s work that was very nearly abandoned completely. ‘I feel like I’m only learning about my voice and starting to feel comfortable. It’s been a very hard subject for me, so much so that on certain albums I’ve said, “I’m not going to sing anymore, this is too hard.” It’s a big suffering. I remember with Alex, recording ¡Ay!, being like, “I can’t do this!” It was just not coming together! I wish I could be one of those singers like Scott Walker, who can push the voice, but I’m learning and taking it very seriously. I practice and try to accept whatever is going on here. With singing, you’re fully exposed.’

In the exploration of honesty for A Danger to Ourselves came an inevitable desire to explore her own vocal expression. ‘It was very deliberate in the sense of thinking, ok, I’m going to try to see what I can do with this voice of mine, with the preconditions of my voice – psychological, emotional, and physical – and try to challenge that: to sing louder, clearer, more upfront, with lyrics that explore sensuality, eroticism, romance, and all these things in bolder ways, less shy of them, but still poetic. Because that’s the framework where I feel comfortable writing.’

In an insightful and wide-ranging conversation with Jamie Liddell for his excellent Hanging Out with Audiophiles podcast (link in the footnotes), when complimented on how ‘amazing’ her voice sounds on this record, Lucrecia responds: ‘That was done at home, I got this U67 [Neumann microphone], the new edition, and I think that helped me a lot to feel the voice, but it was a very patient process.’

David Sylvian’s experience was invaluable. ‘I am a big fan of his work…I always admired the way he crafts music in such a free way, like it doesn’t matter what are the sources: instrumentation, exploration of electronics, but the voice is kind of the centre and the gravity of all that.’

His expertise in the mix played a big part in the how the vocals come across. ‘I have to credit David for that. Because I think his records are precisely so gorgeous and, I mean, he’s an absolutely stunning singer and I can’t compare myself in that way because I really need a lot of time to be able to feel that I did the right take.

‘And also the effects, how it’s compressed, how it’s EQed, this was a whole new ride for me, because watching David do it, he did things I would never do for my voice, which was very fun to see for me. EQing it in extreme ways, like in the high frequencies for example, or compressing it in a way that it was like in your face – I’ve never done that…

‘Definitely, David, I think his biggest contribution was the right placement of the voice, the right effects for it, so that it achieves the space but also has depth. I left that all to him. I did my premix with a simple configuration as to how I wanted it, but I trust him completely. I trusted his ears and vision to do what it needed.’

The lyric to ‘Hasta el Final’ touches on one of the record’s prevailing themes. ‘It’s about reassuring your lover that you have the capacity to carry their existence up until the end,’ confided Dalt. These are ‘love songs that also make reflections about endings, about death.’

‘me confiarías

el peso

de tu cuello

y su penar

y su verdad

y llevarte tan

suavemente

hasta el final

me dejas contener

con mi mirada

ese arenal

ese mental

y que puedas

sentir la simpleza

y levedad

pura y real’

‘Would you trust me with the weight of your neck

and its pain

and its truth

and carry you so gently ’til the end of time

Would you let me contain with my eyes

that dustbowl

the mental one

so that you could feel simplicity

and lightness

pure and real’

‘Throughout the making of this album and the nature of this relationship, I’ve come to think about the end – whatever that means – a little bit more. I guess something that relates to the idea of transitioning, of consciousness.’

Death, says Lucrecia, ‘is very present in the record…That has been a subject discussed with my partner. I guess I’d never met someone that has the awareness of death in a way that is a little bit more naturalised and kind of present, accepted, like in this way that it’s just a transition, transmutation, so to talk about those subjects openly has been very, very meaningful to me.’

‘Stelliformia’ reflects on this transmutation. But it’s a track that may never have come into being. Alex Lázaro flew to New Mexico when work on the album reached the point where the original drum loops he had shared with Lucrecia, and which became the catalyst for many of her compositions, needed to be re-recorded for the final mix. ‘I remember I played what I had to David and Alex, and David said, “I think it’s missing a couple of songs.” And I’m like, “No!!”, because I was so ready to feel, ok we’re going to start finishing it. And obviously in that moment you’re in total denial and you’re like, “No, he’s wrong!” And then obviously I started to feel like, actually, he’s totally right and I should do this, and then I think I changed the flight of Alex and he stayed a couple of weeks more. And so we had a little bit of a chance to improvise more and create from scratch.’

It was during that period that the ‘miracle’ that is ‘Stelliformia’ came into being. ‘It came out of nowhere on one of those days when you’re exhausted in the studio but still feel like you have something to give. Alex started banging the electric guitar bridge with a mallet, and I began processing that signal through my modulars and other effects. Everything just clicked into place within seconds.’

The opening line is based around an ancient Egyptian poem that Lucrecia had shared, dedicated to David, on instagram: ‘The wisdom of the Earth in a kiss and everything else in your eyes.’ ‘I started to think, “OK, how can I give that a little twist from my point of view?”

‘The lyrics came to me while I was driving, and I had to pull into a Home Depot to write them down. It’s a very personal lyric exploring the idea of a love that continues to exist after transmutation, and somehow my very personal response to David’s song ‘A Fire in the Forest’. I sing:

‘The wisdom of candour in your touch

tangled with a life

that begs for transmutation

and I am here, a subtlety,

staring at you from the edge

as I become the fire

that keeps on giving

the fire in my mouth

that carries your life

the fire that rejects

discontinuity

the fire that awaits

for a given wind

that brings with it our life

to extensity’’

‘There is a nebula of ideas and thoughts that I’m accumulating while I’m making the album, that is influenced by books I’m reading and thoughts I’ve been having and conversations with David,’ she said. ‘I like the dedicated attention of just sharing with one person. That you can connect on many levels of intimacy: sharing music, sharing ideas, thoughts, weird concepts or just chilling, going for a hike.’

‘We go very deep talking about consciousness and Buddhism, in that sense of transcendence and that you don’t die, you just change state. Sometimes it’s two worlds: at first they look parallel, but then there’s crossings between them. Somehow musically, they try to interconnect.’

Asked by Mary Anne Hobbs to create an extended ‘director’s cut’ version of one the tracks from the record for her new BBC6 radio show, Lucrecia chose ‘Stelliformia’. Introducing the reimagined version (which at the time of writing can be heard here), she said: ‘This longer version includes an intro with a poem that expands upon the meaning of the word stelliformia. It is derived from the Latin stelliformis, meaning star-shaped. It is first recorded in the period around the 1800s…it’s often used in scientific contexts, particularly in biology or geology, but I like to extend this concept to astrophysics, thinking about the formation of stars in the sky. And wondering, could it be that a star is born when someone dies, from blood pulse to pulsing light?’

In the simple lines that follow, there is hope beyond the human ending…

‘Eardrum on chest

your pulse

a pace

memorised’

‘Blood to light

I’ll recognise it in the dark sky’

‘Blood to light

I’ll find you’

(my transcription)

‘In this relationship, it is the first time I feel something… I guess the best word would be “transcendental”,’ she declared. This is her ‘most mystical record, for sure.’

Thoughts of her own mortality were brought sharply home during the run up to the release of A Danger to Ourselves when Lucrecia, who lives with epilepsy, suffered a seizure which caused her heart to stop beating for eight seconds. It was on the same day as the release of her single ‘Caes’ (which takes a different angle on the subject of death). A previous episode back in the summer of 2023, during the intense touring schedule to support ¡Ay! and parallel recording commitments, had been one of the driving factors behind her decision to retreat to concentrate solely on the production of the new record.

Thankfully, news was soon posted of her recovery and return home. ‘I don’t know what the seizure did to my brain but I think it must have rewired something because I’ve been feeling also very like, ok, I need to be full-on in this world, like this is my chance or something, I don’t know. Very very intense, very beautiful…’

‘You are the only one that I can fool death with’

from ‘Divina’

There is a symmetry in the presence of David Sylvian in both the opening and closing tracks on the album. Spoken word was his contribution on the first, and blues guitar his part on the last. ‘It took me quite a while to understand what I needed to do to it, lyric wise and sonic wise,’ says Lucrecia. ‘My initial idea was to craft a blues that felt frozen, as if coated in monstrous tar – an icy, suffocating heaviness. Then David came up with the name ‘Covenstead Blues’, which resonates perfectly with the themes woven into the lyrics.

‘I thought about the raw power of the blues – its ability to name pain – and how to channel that into a song that explores rage. It’s a voice for what’s been left unspoken to a toxic friend, one that drains your energy with no consideration. I sing:

‘May I blow you up

malignant goddess

may I burn down

your bittersweet

kindness

or you’ll continue

disguising your grief

your tenderless reach

exhausting!’’

It may sound like a very personal attack, but ‘‘Covenstead blues’ is not specifically to any one person,’ its writer insisted. ‘It’s about anything that threatens your capacity to have tranquility, to have control, to not have fear.

‘I have the capacity to blow it up because it is a “malignant goddess.” There’s a joy in writing something so crooked. If you apply it to a person, it’s f*cked up. But you can apply it to the thing that creates your insecurities, either through a person or through thought…I think fear is a big one, right? We’re living in a moment in which fear is being implanted in us constantly everywhere. So it’s a question of how much you allow that narrative to be imposed on you.’

Sylvian’s thick-as-treacle guitar rings out strident and clear. There’s a defiance in this track that chimes with the singular creative drive of both Lucrecia, in bringing this latest work to fruition, and David, who has carved his own artistic path over decades and brought his own experience and expertise to bear in service of partner’s vision for her work. It’s exciting that their lives have crossed in this way. I wish them happiness and creative fulfilment.

‘I look forward to composing in totally different ways after this album,’ says Lucrecia. ‘I feel like it’s the beginning of a new space, or something like that, in which I’m more honest with my voice, more honest with my compositions. I’m not fearing genre. I’m not fearing a lot.’

This time, in the main, the words existed before the music. The next project might be different. ‘By living with David, I’m starting to learn more of the versatility, being more free to accommodate words to a song. My intuition tells me that maybe for our next record I will have more tools to adapt a text to a song more freely, instead of the other way around, which is usually what I do.’

Footnote:

Having cashed in some air miles to visit a city with art galleries that I’ve long wanted to visit, it was my pleasure to witness Lucrecia perform the entirety of A Danger to Ourselves at Johnny Brenda’s in Philadelphia on 30 October. The live trio included Jonah Minkus on drums and Cyrus Campbell on bass. More shows are promised in the new year with Lucrecia indicating at the album’s bandcamp launch listening party that ‘we are working on a very exciting show in the UK around May, more details soon!’ Catch the upcoming tour if you can.

‘Covenstead Blues’

Cyrus Campbell – electric bass, contrabass; Chris Jonas – soprano and tenor saxophone; Eliana Joy – backing vocals; Alex Lázaro – percussion; David Sylvian – electric guitar solo; Carla Kountoupes & Karina Wilson – violin; Amanda Laborete – cello; Lucrecia Dalt – all other instruments, vocals

taken from the full album credits

Music and lyrics by Lucrecia Dalt

Mixed by David Sylvian

From A Danger to Ourselves by Lucrecia Dalt, RVNG Intl (2025). Produced by Lucrecia Dalt and David Sylvian.

‘Covenstead Blues’ – official YouTube link. It is highly recommended to listen to this music via physical media or lossless digital file. If you are able to, please support the artists by purchasing rather than streaming music.

This article has been put together with input from many interviews undertaken by Lucrecia Dalt to mark the launch of A Danger to Ourselves. As always, I am grateful to the original interviewers and publishers. All quotes are from 2025 unless otherwise indicated. Full sources and acknowledgements can be found here.

Jamie Liddell’s Hanging Out with Audiophiles podcast featuring Lucrecia Dalt can be heard here.

The featured image is the cover of A Danger to Ourselves, photograph by Yuka Fujii.

Lucrecia Dalt official sites: website, instagram, threads, bluesky, x, bandcamp, facebook

Download links: ‘Amorcito Caradura’ (bandcamp), ‘Acéphale’ (bandcamp), ‘Divina’ (bandcamp); ‘Hasta el Final’ (bandcamp); ‘Stelliformia’ (bandcamp); ‘Covenstead Blues’ (bandcamp)

Physical media: A Danger to Ourselves (bandcamp)

‘David is my partner and so I was here with him during the whole process of making the album and he was a big part in being like a tandem collaborator: ears, thoughts and then mixing the record and contributing along in production decisions too.’ Lucrecia Dalt, 2025

love her music, its so intense and has such an interesting unique approach to song writing – its a place David should have ended up, but for that English reserve 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interviewer: ‘You mentioned David Sylvian. What energy does he bring to recording, and how do your working methods differ?’

‘He gave me a lot of confidence to trust my own vision and he also encouraged my freedom in decision-making. David is someone who doesn’t want to hear a demo until the person feels that what they’ve got is ready to share. I’m someone who can share very raw demos with almost nothing there to try to see if the person will react to it. So that was an interesting contrast in how we work.

He won’t show me something until he feels it’s absolutely there. And with my friends, with Alex [Lázaro] and Camille [Mandoki], we’re sharing demos all the time – like, “What should I do here?”. Being with him, I started to appreciate that maybe you should trust yourself more in the process and see how far you can go with an idea before sharing it. That was a very interesting learning curve.’

Lucrecia Dalt, Electronic Sound, issue 132, 2025

LikeLike