My previous conversation with Melaine Dalibert came at the culmination of his four albums on Yuko Zama’s elsewhere label. From the opening disc, Musique pour le Lever du Jour (Music for the Break of Day), released in 2018, to Night Blossoms in 2021, each instalment had a connection with David Sylvian. The sleeve art for each cd was provided by Sylvian, who also proffered production advice and project titles, a track was dedicated to him, and he contributed electronic ‘sound work’ to the tracks ‘Yin’ and ‘Yang’ on the final release in the series. (Read that interview with the full background to the elsewhere series here.)

An announcement from the Ici d’ailleurs label earlier this year brought news that the partnership between Dalibert and Sylvian would be extended and deepened through an album issued under their joint names, Vermilion Hours, as part of that label’s Mind Travels sub-label. The new release would be Dalibert’s third contribution to the series. ‘Created in 2014,’ declares the label website, ‘the Mind Travels collection is an ode to experimental, ambient and neo-classical music. Inspired by an introspective and immersive aesthetic, it features a visual identity [de]signed by photographer Francis Meslet…Mind Travels invites listeners into a sensory experience, where industrial, atmospheric and minimalist sounds combine to create works that are as contemplative as they are haunting.’

Whilst Melaine had been delighted to have his music handled by Yuko’s US label, his connection with the French imprint stemmed from a desire to create a closer circle in Europe for the production and distribution of the work. Ici d’ailleurs, he said, offered ‘an ideal balance between different aesthetics which have their roots in both popular and contemporary music.’ His first contribution to Mind Travels was Shimmering, released in March 2022, just nine months after his most recent disc for elsewhere, Night Blossoms.

‘When I conceive an album, it is important to me that it has its coherence,’ Melaine told me when we reconnected recently, ‘that the pieces that constitute it are both autonomous and contribute to an overall balance. The album Shimmering responded to a strong personal desire, which arose after having explored algorithmic composition for several years, to write more melodic, more intuitive pieces, adopting the format of instrumental songs. In a way, a desire to register in the lineage of the romantic piano, music made “for the hand” and to “make the instrument sound”.’

The approach taken by Dalibert, a professor of music at the Conservatoire de Rennes, echoes that taken for his elsewhere album Infinite Ascent, where the use of hand-devised algorithms was also temporarily set aside. ‘The compositions that make up the album Shimmering were all written during the start of the Covid crisis,’ said Melaine at the time of release. ‘For me, it was a moment when I thought a lot about the way I envisaged [a] concert, and in particular about what distinguishes a “discographic” project and a “live” project. Let’s say that this new repertoire, I designed as material more conducive to sharing on stage, which requires a certain density, energy. I think I can achieve a balance in my work, by linking my most radical compositions with these more “pop” pieces.’ As is often the case, Melaine illustrates his point with a reference from the world of visual art. The contrast ‘between two different techniques interests me a lot,’ he said, ‘as can be seen in the production of a visual artist like Gerhard Richter, who works as much in abstraction as in ultra-realism.’

I was privileged to witness Melaine performing this repertoire at Cafe OTO in April 2022. An intimate evening sat close to the performer at the venue’s Yamaha C3 grand piano, witnessing the acoustic resonance of the instrument rather than purely amplified sound. Melaine’s absolute focus and dextrous touch created a pool of calmness in the midst of London’s never-ending busy-ness.

It’s striking that for Shimmering, Melaine is accompanied on several of the pieces. In what appears to be an extension of the previous experiments with Sylvian on ‘Yin’ and ‘Yang’, Fabien Leseure conjures electronic ‘soundwork’ for the track ‘Mantra’, and four compositions feature violin from Margaret Hermant. Following the solo piano of the opening (and title) track, the first piano-with-violin piece is the two-minute miniature ‘Dérive’, which is a thing of aching beauty. The perfect denouement, ‘Épilogue’, crowns the approach with a touching tenderness.

‘With rare exceptions, my music borrows its voice from the piano,’ Melaine says, ‘and if my writing seeks to be as refined as possible, it happens that I feel the need to enrich it with new timbres, to make something other than the hammers on the strings heard. My music first appears to me in a rather formal, even conceptual way, and then it finds its true life in the acoustic and sensitive world, the experience of the record or the concert, which sometimes calls for a few artifices.’

The photographer Francis Meslet, in Melaine’s words, ‘gives a visual unity to the Mind Travels series with his singular talent. His work essentially focuses on the effects of time on buildings that are often abandoned by civilization. On the cover of my album, you can see an interlacing of vaults in a religious building, which echoes the patterns that run through my music.’

Following a further set of pieces devised free from the algorithmic approach – put out in 2023 in vinyl and download formats on the Japanese FLAU label under the title Magic Square (and well worth seeking out) – Melaine felt the need to ‘reconnect with generative writing, and a desire to work on the stretching of musical time.’ This would lead to his next two instalments for Mind Travels, Eden, Fall (2024) and the new album co-credited with David Sylvian, Vermilion Hours.

‘Eden’, is the longest piece on the first of these discs, running at over thirty-seven minutes. First impressions are that the same piano motif is being repeated, but it soon becomes clear that the timing is changing, intervals are extending, giving an impression of the distortion of time precisely as Melaine describes. After the brief, cascading, ‘Jeu des Vagues’ (‘Game of Waves’), comes the rhythmic ‘Fall’. At first the time is beaten out on wood, perhaps the structure of the piano itself, before repeated notes join the unfaltering pulse. It’s unsettling to the point that, as the label’s reviewer stated, you want to return to the balm of the opening track as soon as the running order is over, and so the pattern of listening repeats. Melaine: ‘The album Eden, Fall reconnects with systematic writing, with three pieces that make us experience the perception of musical time and repetition very differently.’

For his latest release, Dalibert chose to revisit an earlier opus. ‘The album Vermilion Hours is based on two compositions, one of which is a reworking of my ‘Musique pour le Lever du Jour’ from 2018,’ Melaine told me. ‘The second, entitled ‘Arabesque’, is a more recent piece which explores the harmonic spectrum of a fundamental F through different motifs. Potentially infinite, these two titles are both presented over a duration of twenty minutes, which I particularly like.’

So why go back to a piece that was originally crafted over a two-year period and had been previously released? ‘My composition ‘Musique pour le Lever du Jour’ is probably the one that has accompanied me the most since writing it in 2018. I play it regularly in concert, in diverse and sometimes striking contexts (notably once at dawn in the Pyrénées massif). With each experience, I tell myself that this piece could be played even more quietly, and I believe that it was first of all the desire to offer a slower version that motivated this reinterpretation on disc.’

It was in September 2021 that Melaine played this piece outdoors at the Chapelle de Roumé in Cieutat, deep in the south of France and overlooked by the mountains. Performing as the sun rose, it’s easy to imagine how the gently mutating music would have suspended the audience in a moment of wonder and contemplation at the dawn of a new day. ‘Slow tempo, meditative spaces, harmonies in symbiosis with the colours of the first light,’ read the publicity, encouraging attendance for a 7am start. ‘It is autumn, nature awakens, and you are part of it!’

A couple of months earlier, Melaine had again performed the piece at dawn, this time at the Musée cantonal des beaux-arts in Lausanne, Switzerland, within the gallery where Italian sculptor Guiseppe Penone’s tree sculpture, ‘light and shadow’, is exhibited. Photographs from the event show his grand piano silhouetted against the morning light which cascaded in through a spectacular arched window.

In these solo piano performances, the rich resonance of the single piano notes, sustained through use of the instrument’s pedal, would have converged in a gentle mist of decaying harmonies, just as they do on the original recording for the elsewhere label, which lasts for over one hour.

excerpt from the track from the 2018 original release, a solo piano performance, artwork by David Sylvian

For the new recording, however, there would be a new perspective. ‘I had this intuition that this composition, very strict in its generative process, could benefit from a so-called baroque treatment. The electronics bring, in a certain way, an ornamentation that I could not conceive through writing. David Sylvian’s participation in this album seemed obvious to me because I was looking again, as for ‘Yin’ and ‘Yang’, for a counterpoint that is not narrative, but of timbre, of colour: comparable to the background of a painting by Paul Klee, which gives all its vibrating force to the work on form and motif.’

‘Yin’ and ‘Yang’ showcased Sylvian’s ‘subtle way of participating in the resonant halo of the piano.’ For Vermilion Hours, the ‘minimalist aesthetic’ of the pieces ‘requires surface, space.’ Sylvian’s contributions are similarly understated, but their presence fundamentally changes the listening experience of ‘Musique pour le Lever du Jour’. All of the musical ‘attack’ comes from the striking of the piano keys, yet listening to the new interpretation I am struck by how one’s experience of the piece is influenced by what happens between those piano notes. The presence of a gently wavering organ-like drone roots the music, whilst electronic tones extend and sometimes echo the acoustic sound.

Occasionally, there is an intervention that seems unrelated to the piano score. Melaine’s original sleeve-note for the piece says, ‘Beyond its evocative title, ‘Musique pour le Lever du Jour’ doesn’t seek to be descriptive. It could as well have been evening music or any series of transient moments in the day.’ Visualising those early morning performances, though, it’s difficult not to be seduced by the imagery of the slow transition from night to day. In this context, Sylvian’s complementary sounds bring to mind sunlight gently illuminating the landscape, rays bursting over the horizon and glinting off water, a calmness disturbed only by the flight of birds gliding across the skyline. Back to Melaine’s sleeve-note: ‘Like a mysterious law of nature, the algorithm distils quiet and unpredictable pentatonic spells, and without even realising it we are dragged into new landscapes…’ (2018)

‘As with the pieces ‘Yin’ and ‘Yang’, we worked remotely, exchanging information via computer,’ says Melaine of the collaboration with Sylvian. ‘The idea wasn’t to commission David with the aim of remotely controlling his work, but to give him the freedom to offer his own interpretation of the music. His suggestions once again immediately won me over on the two tracks that make up the album.’

Melaine’s comparison between Sylvian’s work on Vermilion Hours and the background of a Paul Klee painting is a fascinating one. ‘I am intensely sensitive to the visual arts and particularly to the work of certain painters and photographers,’ he told me, ‘but it is important to understand that the connection that can be made between music and painting is of a rather complex nature. It is not a particular painting that inspires a piece of music. It is rather: how can a technique, tested by perseverance (think, for example, of Monet’s Nymphéas [Water Lillies], Mondrian’s systematic divisionism, Marden’s technical expression…) instil a certain radicalism, a certain rigour of the creative gesture?

‘In a certain way, painting has a powerful force of authority, through its material reality. And I feel intimately concerned with this strange relationship with reality, which in itself doesn’t care about the subject. David’s intervention in my music doesn’t operate at a narrative level, it brings a light, a varnish which is not superficial but which reveals its contours.’ Hence the parallel with ‘Paul Klee’s canvases, where he would prepare his backgrounds for weeks. That’s what gives the forms and figures their depth.’

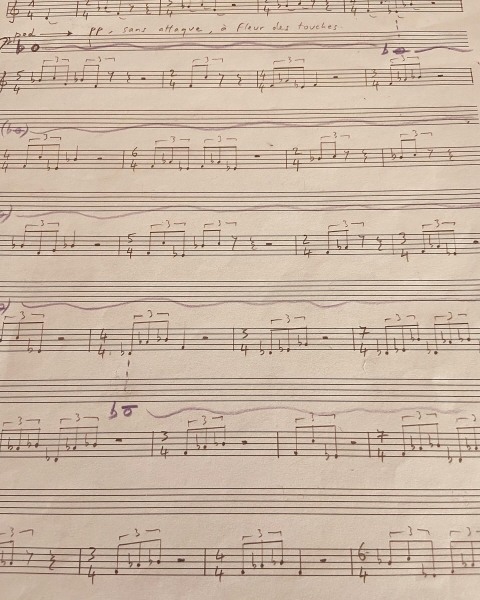

Looking at just a brief excerpt of the handwritten manuscript for ‘Musique pour le Lever du Jour’ offers a fascinating insight into how the sense of ‘stretching time’ is achieved. Time signatures change every bar. The notes in each triplet mutate. The rests at the end of each bar vary. The experience of listening to these long-form compositions is very different from one that moves through a series of movements or trades a number of musical themes. As mentioned in my previous article, I found this unfamiliar at first and a challenge to quieten my mind sufficiently to engage. Familiarity has brought the ability to surrender to the gradual progression within the music, and to live in that moment.

The reduced duration of the new version of the piece – around a third of the length of the original recording – is, Melaine says, ‘a format, that of an LP side, in which I feel comfortable performing live.’

‘My writing is quite theoretical, very systematic,’ says Melaine. ‘But I believe any system must be humanised to be truly moving. My aim was to subject these rational, “clinical” compositional methods to an organic transformation. The electronics do not act as a counterpoint or narrative contribution, but rather as a vibration, an aura.’

‘Musique pour le Lever du Jour’

Melaine Dalibert – piano; David Sylvian – electronics

Composition by Melaine Dalibert

From Vermilion Hours by Melaine Dalibert & David Sylvian, Ici d’ailleurs, 2025

Download links: ‘Musique pour le Lever du Jour’ (bandcamp); ‘Dérive’ (bandcamp), ‘Épilogue’ (bandcamp); ‘Eden’ (bandcamp)

Physical media: The three Mind Travels releases mentioned in this article are:

Shimmering – Melaine Dalibert (bandcamp)

Eden, Fall – Melaine Dalibert (bandcamp)

Vermilion Hours – Melaine Dalibert & David Sylvian (bandcamp)

The featured image is Francis Meslet’s cover for Vermilion Hours

Many thanks to Melaine Dalibert for his generous contribution to this article. All quotes are from 2022-2025 unless otherwise indicated. Full sources and acknowledgements can be found here.

‘I no longer felt entirely in sync with the slightly rushed tempo of the first version – I wanted to align it more closely with what I feel is the right “energy” for this music.’ Melaine Dalibert of ‘Musique pour le Lever du Jour’, 2025

Read the sister article:

More about work in the 2020s:

2022 – Dumb Type

If I Leave No Trace

Cherry Blossoms Fall

Grains (sweet paulownia wood)

Love your work David! I’m (and have been for longer than I’d care to recall) besotted with the work of DS, whose work resonates in a way that no one else’s quite can. Your thoughtful prose illuminates the work of a poet and evidently, a scholar very well. Kudos to you.

Regards,

Ally

LikeLike

Thanks, Ally, for the kind feedback. It’s truly appreciated. Thank you for reading.

LikeLike