‘Thalheim is a place in Germany,’ states David Sylvian factually on the promotional interview cd that was provided to journalists when Dead Bees on a Cake was at last released by Virgin. ‘A place where another famous Indian saint lives and receives people from around the world. I visited her there and the song touches upon that and my relationship with her.

‘It’s also about my relationship with my wife. It works on a whole series of levels. It’s another love song, coming out of a very difficult period in my life and this is talking about redemption through love.’

In fact, the small town of Thalheim was one of the first places that Sylvian and Ingrid Chavez visited together after their worlds collided so dramatically. It was a trip that symbolised a shared intent to investigate more of what might be called the “spiritual life”. ‘It sounds so cod, doesn’t it?’ said Sylvian, struggling to find the appropriate language to address the subject. ‘I hope it doesn’t come through the work in that way. It’s more in search of a philosophy or discipline with which to focus your life, or for me to focus my life; and Ingrid felt the same way.’

To this point, Sylvian had found an ideology that resonated but, untutored and unnurtured, the path had only led so far. ‘The point for me was to find a discipline with which to work in life on a daily basis. I was and still am very interested in Buddhism, particularly Zen Buddhism. And that has informed my practice. Working alone, because I’ve never had a teacher, the practice became very dry and ultimately didn’t inform my life enough. When I met Ingrid we kind of made a pact that we were going to explore that aspect in our life together. It was a common goal between us.

‘We start to see different teachers. It gives us a focus and gives us a discipline and somebody to constantly inspire the practice.’

The influence of a small number of Indian holy women is acknowledged with evident gratitude in both the lyrics and the sleeve-notes of Dead Bees on a Cake. The visit to Mother Meera was the first of these encounters and was a shared revelation for the couple. ‘Shortly after we met, we went to visit Mother Meera in Germany, and that increased our level of devotion, and we increased the amount of time we spent applying ourselves to practice. A while later we met an Indian avatar by the name of Mata Amritanandamayi, and she became my guru and is still my guru. And further down the road, Shree Maa actually came to our house in Minneapolis to stay for a period of time, and that was a tremendously transforming experience also.’

Sylvian again grasps for the right terminology to adequately convey the impact of the visit to Thalheim, but the profound influence on his life and outlook shines through as he seeks to put it into words a few years later. ‘I visited Thalheim for the first time in ’92. Oh god, what did it mean to me? It was the beginning of the journey in earnest. It was the rebirth of love. I can’t do better than that, I’m afraid.’ (2003)

Mother Meera was born Kamala Reddy in Chandepalle, India in December 1960. The child of a poor farming family, she works as a domestic for the neighbouring household whilst still a young child. These are the landowners to whom her parents provide their labour, also happening to share the surname Reddy. In time, the son of her employers returns from travels through which he has been seeking spiritual fulfilment in the wisdom of gurus. When he sets eyes on the young Kamala, aged just 11, he is immediately convinced that she is a manifestation of the Divine Mother herself. ‘Uncle’ Reddy takes her under his wing, a path that leads her to an ashram in Pondicherry where another avatar, Sweet Mother, has recently departed this life. By the time she resides there, Kamala has taken the name Mother Meera and starts to receive visitors for a blessing.

Overseas devotees encourage her to travel and she visits first Canada and then Germany. The latter becomes her home at the start of the 1980s, a period in which Uncle Reddy experiences poor health. She settles in Thalheim with Adilakshmi, a spiritual companion whom she met in Pondicherry, and here they must bury the Uncle in the town’s churchyard.

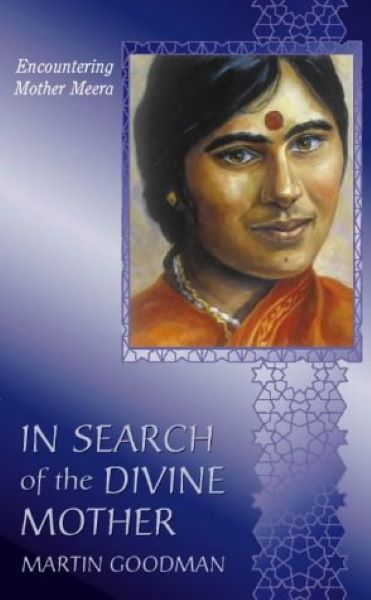

Whilst we know Sylvian’s response to what he experienced in the presence of Mother Meera, we don’t have a direct recollection of the meeting. There is, however, a contemporary account of what was involved with just such an encounter in Martin Goodman’s out-of-print book In Search of the Divine Mother. It was 1991, the year previous to David and Ingrid’s first visit, that Goodman’s curiosity drew him to check things out first-hand. As with other visitors, he stayed in a guest house in one of the neighbouring villages.

‘I am walking down the hill toward a German village because people say God lives there,’ writes Goodman. ‘She is at home for the evening and receiving visitors.

‘Two old men sit on a bench beside the path… “Where are you going?” one asks.

‘I point across the fields. “Down to the village of Thalheim. To visit Mother Meera.”

“…Where are you from?”

“England.”

“Then you must be Christian. Why do you come? Why do people come from all over the world? What do they expect from this Mother Meera?”

‘His companion looks up. “She doesn’t perform any miracles, you know,” he advises.

“I know. I don’t want miracles,” I lie. We all would like some miracles, even if we don’t believe in them. “I am a writer. I have to see things for myself so I can write about them.”

‘This is the summer of 1991. Pears ripen on the trees beside the lanes, the forests and lands are green. The village of Thalheim nestles in a basin formed of wooded hills and fields. The spire of St Stephen’s church rises from the centre of the village, and streets lined with solid, substantial houses radiate from it. A public bar, The Hunter’s Rest, sits below the church, and the village supports a small baker’s, a grocer’s, and a savings bank. People who live in Thalheim do not chase excitement. They opt for comfort, a family life lived within the expansive walls of home, and a barrier of miles of gentle countryside between themselves and the outside world.

‘Mother Meera lives in one of these houses. The stream that crosses her rear garden forms one of the boundaries of the village. The broad hill that rises beyond it is uncluttered by housing.’

The rural setting is apt for the simplicity of these events.

‘In 1991 the organisation of these evenings with Mother Meera is still loose. People are mostly drawn by word of mouth. They do not need to make reservations, and all who come can be accommodated. Many fly into the international airport at Frankfurt…That evening there are about sixty of us. We mill around in the courtyard of the house, some trying words of contact with strangers, others maintaining silence. We are preparing to enter a holy and unfamiliar space. We slow our movements down and soften our noise.

‘The door of the house opens. A woman steps back in a rustle of thick silk to let us enter. The orange of her sari, rich with embroidery, suits her well. It shines like a beacon.’ This is Adilakshmi, the companion who has shared Mother Meera’s journey from India to Germany and who recognised the spark of the divine within the teenage girl when they first met.

‘In the West we are familiar with the masculine version of God,’ Goodman explains, ‘as in God the Father. This God once became incarnate on earth through his son, Jesus Christ. The feminine version of God, the Divine Mother, some find in the Virgin Mary. The Divine Mother is worshipped in many forms throughout India, where she is considered responsible for the creative cycle of life. She is the force behind birth into life, growth through life, and transformation through death. She sometimes comes to earth in female form. For Adilakshmi, Mother Meera is unquestionably the rarest of beings, the supreme Divine Mother, a direct incarnation of God on earth.

‘We walk in our socks across the gray marble floor of the audience room. It is large enough to seat us all comfortably, in rows of white plastic chairs. The chairs are grouped on either side of the centre of the hall. The centre is cleared for any visitors who prefer to sit on cushions on the floor, but mostly it gives people a clear passage up the feet of Mother Meera. She will sit in the arm-chair set against the wall to face this vacant space.’

There is nothing to rouse the atmosphere. Nothing to play upon the anticipation of the visitors or to sensationalise that moment. In fact, the absence of sound is the hallmark of the whole experience.

‘The room settles into silence. The silence is individual at first, as people place themselves in this new environment. Then the individual silences become aware of each other, they touch, they merge, and a general silence grows to contain everybody and gather focus. It reaches through the doorway and probes the unseen staircase that leads to Mother Meera’s apartment two floors above. The church clock strikes seven but we already know the time, for this is the hour of Mother Meera’s appearance, and expectation has peaked. We rise to our feet and listen for the first distant whisper of her approach.

‘The stage is set. A collective silence holds the audience. As the principal figure enters, we note her costume is superb. Mother Meera wears a sari of deep purple, alight with embroidery of silver thread.

‘She is short and slight. Thick socks cover her feet, which are hidden below the sari’s silk. Her eyes look to the floor as she shuffles forward. This is not the entrance of a crowd pleaser. It is the entrance of someone who chooses to be lost in a crowd if she has to come out at all.’

Compare that description with David Sylvian’s poem ‘The Church Bells Strike’, first published in Trophies II and sequenced between the Sylvian/Fripp lyrics and those for Dead Bees on a Cake. Surely this is a recollection of the same scene? Maybe it also acts as a figurative description of the Divine Mother descending to earth.

‘The church bells strike

And ring dully into our collective silence

A gentle creaking of floorboards

Splinters from the room above

In the distance a dog barks

A car crudely kicks up its engine and pulls away

All activity strangely animated by our stillness

Silence once more

Then footsteps

She’s begun her descent

Accompanied by the sweep and rustle of her dress

In anticipation we turn our heads

So as to catch the muted drama of her entrance

An explosion of colour and light

A humming, faint but distinct

Unheard but acknowledged all the same

And nature buzzes drunk on the blood of the sun

Radiating love, peace and compassion

She is among us.’

‘She seats herself in the armchair,’ Goodman continues, ‘and the audience sits too. For those of us used to more entertainment than this, this evening will seem long. There will be no amusement. There will be nothing to distract anyone from a very personal view of the evening’s experience.’

There are two distinct phases of the ritual as people move forward for time one-to-one. For the first, the visitor’s head is lowered whilst the Mother gently touches the individual’s temples; secondly, they each sit upright and share eye contact, direct and unabashed.

‘Adilakshmi is the first to move. She rises from her chair, and the thick silk of her sari crackles as she kneels on the carpet in front of Mother Meera’s feet. She shuffles forward so her head is bowed between Mother Meera’s knees. Adilakshmi’s hands clasp the toes of the feet in front of her, and she closes her eyes. Mother Meera reaches forward. Her fingers press against the sides of Adilakshmi’s head, a fingertip hold of gentle pressure…Her hands rest on a person’s head for around twenty seconds. As Mother Meera releases the fingertip hold on Adilakshmi’s head, Adilakshmi sits back on her heels and opens her eyes. She is now staring into the eyes of Mother Meera, who gazes back at her.

‘This is all we newcomers see – two women bright in their Indian saris, one kneeling and one sitting, looking into the other’s eyes. The younger woman’s head pulses backward and forward slightly, but her eyes do not blink.’

This is darshan, where an individual beholds the sacred and in doing so receives a blessing. The silence is not broken for any words to describe what is happening, but in Mother Meera’s book Answers (1991) she explains that as a person kneels in the first part of the ritual, she is working with light to untie knots in a white line that runs from the toes to the head of the individual before her. When that person rises to meet her gaze, ‘I am looking into every corner of your being,’ she clarifies. ‘I am looking at everything within you to see where I can help, where I can give healing and power. At the same time, I am giving Light to every part of your being. I am opening every part of yourself to Light. When you are open you will feel and see this clearly.’

Martin Goodman continues his account of his first evening in Thalheim. ‘The person before me rises. I dive to the floor and plant my hands on the ground on either side of Mother Meera’s feet. The Hindu custom of clutching of a master’s feet seems indelicate and presumptuous to me with my Western ways.

‘My eyes are closed. I come to know Mother Meera through her touch. The lightness of her tiny fingers plays itself about my head. It is a hold, not a grip. A shower of warm rain might exert a similar pressure.

‘Then the hands are lifted. I feel the loss of their weight, though the pressure of Mother Meera’s fingertip hold still lingers and will return over the days to come.

‘Sitting back, I open my eyes. I keep my glasses on, for I want to see as much as I want to be seen. This young Indian woman I have never met opens her eyes before me.

‘It is a gesture of astonishing intimacy, the eyes wide and round, hazel brown merging into the black spots at their centres. Yet while the eyes are supposedly reading the condition of my life and suffusing me with light, they do not seem invasive. It is like looking into a broad expanse of water, as soft as that, a look that washes all around me.

‘Her face is without expression, but she is also young. Youth has an expression of its own that coats a young face in purpose. I look at Mother Meera, watch some wave pass above the skin of her cheeks to ease them into an invisible smile, and catch some gleam of play and love in her eyes.

‘Then the eyelashes, so long and so black, slowly close over her eyes. She tilts her head forward and it is time for me to stand.

‘As I walk back to my chair, her hands have already alighted on another person’s head.’

From Sylvian’s words we understand that the experience was profound for him, just as it was for the author who visited only a few months earlier. Certainly, amidst the unfamiliar aggression of some pieces on Sylvian’s joint album with Robert Fripp, The First Day, there are two lengthy tracks which bring firstly hope and then calm amidst the confusion. ‘Darshan’ is directly influenced by the visit to Thalheim and the title of the frippertronics piece that brings resolution as the record closes, ‘Bringing Down the Light’, is appropriated by Sylvian from Mother Meera’s gift of bringing down the Paramatman Light – God’s light.

‘There is a stillness at the end,’ Martin Goodman recalls, ‘after everyone who wishes to approach Mother Meera has done so. She sits, regarding her knees, in case anyone needs this extra time to come to her. Then she stands.

‘Everyone rises as she walks out of the room. Bodies stretch and language slowly returns. For more than two hours no one has spoken, no one has left the room. Some have been bored, some in bliss, but everybody has shared in a period of meditation. It is unusual to sit in silence for so long. Many are pleased with their own endurance, just as they are delighted to be free to move and talk again.

‘Mother Meera is in her apartment at the top of the house, making her usual cup of instant coffee, as I walk up the hill and away. I think I am leaving her behind. I don’t yet understand the effect of gazing into her eyes. I don’t know that something of Mother Meera now travels with me. I have just encountered what grow to be the greatest mystery of my life.

‘Though I will come back to Thalheim and Mother Meera, part of me is already fixed in the landscape. It never leaves.’

The interplay in Sylvian’s lyric between devotion to Mother Meera and to his wife is evident from the very first line of the song, moving on to describe the redemptive love discovered in each relationship:

‘Couldn’t leave you if I tried

Couldn’t weather this alone

And through the darkness you still provide

The sweetest love I’ve ever known’

‘The song kind of documents my experience with that teacher, but it also documents my experience with my wife so I can’t actually differentiate between the two in the track,’ explains Sylvian. ‘They just kind of merged into one because I experienced them with Ingrid and I experienced Mother Meera with Ingrid. I guess I’ve tried throughout the album not to be too dogmatic about what it is that draws me to certain conclusions and draws me to write about these experiences. As I’ve always done, I’ve tried to leave the pieces quite open to interpretation. Some of the pieces are directly about my own relationships with certain teachers and can be interpreted as a one-on-one relationship, or a personal relationship so that it enables other people to connect with the work.’

The light that Mother Meera seeks to bestow into the lives of her visitors is surely referenced in the songwriter’s call for his own pathway to be illuminated:

‘Take the shadow from the road I walk upon

Be my sunshine, sunshine’

And this love has the power to restore wholeness, repairing the pain and brokenness expressed so recently in another song (see ‘Damage‘):

‘The damage is undone

And love has made you strong

Heaven gave me mine

Thalheim’

The song may be named after a specific geographic location but the experience found there is symbolic, making it a metaphor for other journeys and adventures, both physical and spiritual, reaching as far as Shahbagh gardens in Dhaka, Bangladesh, home of another significant ashram.

‘From the foothills to the mountains

On the waters of the Rhine

Face to face in Shahbagh gardens

In communion out of time

Thalheim’

There are some beautifully poetic lyrics as Sylvian expresses an unmitigated joy that transcends the contradictions in life, the ‘everything and nothing’ and ‘disharmony and rhyme’.

Martin Goodman came to see fallibilities in Mother Meera that caused him to doubt that she could be more divine than human, not least comments made (and since rescinded) indicating that homosexuality was not consistent with the law of nature. He remained convinced, however, of the truth of his experience of love and light in the silence of darshan. ‘When we look into the eyes of Mother Meera,’ he concludes his book, ‘the love of a divine mother looks back into our soul. The light of that look is a call to action. It is a call to emerge from the shadows of our lives and truly live. We are shown all of our life’s possibilities.

‘This is the essence of Mother Meera. We come to see her, and we are presented with our possibilities. The rest is up to us. We can choose to live in shadow – or in light.’

‘Be my, oh be my sunshine’

‘Thalheim’

Tommy Barbarella – rhodes; John Giblin – bass; Steve Jansen – percussion loop, cymbals; Ged Lynch – original drum track; David Sylvian – drum programming, guitars, and keyboards; Kenny Wheeler – flugelhorn

Music and lyrics by David Sylvian

Produced by David Sylvian. From Dead Bees on a Cake, Virgin, 1999.

Lyrics © copyright samadhisound publishing

‘The Church Bells Strike’ © David Sylvian

All quotes by David Sylvian are from interviews conducted in 1999 unless indicated. Sincere thanks to Martin Goodman for documenting his first visit to Thalheim so beautifully. Full sources and acknowledgements for this article can be found here.

The featured image is a detail from the multi-panel inlay to the cd release of Dead Bees on a Cake.

Download links: ‘Thalheim‘

Physical media links: Dead Bees on a Cake (burningshed) (Amazon)

An extended vinyl version of Dead Bees on a Cake was released in 2018 (burningshed) (Amazon)

‘The period following on from …Beehive was the hardest of my life. That descent into hell I spoke of. Great mental suffering. Yes, what felt like a monumental shift in awareness and development took place after four years of darkness (a darkness in which, although denied light, I never lost awareness of the light that underpins all existence). It was at this stage after numerous attempts had been made to understand the nature of the experience I was going through (including a beneficial period of psychoanalysis) that I found the first of my teachers.’ David Sylvian, 2003

More about Dead Bees on a Cake:

I Surrender

Pollen Path

All of My Mother’s Names (Summers with Amma)

Praise (Pratah Smarami)

Darkest Dreaming

The Scent of Magnolia

Thank you for another well researched, interesting and enlightening post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you again for your ethereal site and polished writing. I agree completely with Douglas.

Strangely perhaps, I connected with the very end of the piece, and David Sylvian’s reference to his “…beneficial period of psychoanalysis…”. I still prefer his early output (with Japan and his early solo work), though to be fair, I am not considering this objectively, as a critic, say, and I have heard only a limited amount of his music post 1991. I find it staggering that none of Japan’s original members (according to at least one early interview) could actually play anything at the start and yet from 1974-1991 they became, in my view, very accomplished, particularly from 1980. I wish they had been able to have done more together, but no one can take away what they did…Beautiful Country is a move back, for me, of promise, a bridge (metaphorically) between 1991 and 2017 (the year David revealed it). I’ll always like his persona, his more commercial work, and I will keep listening to some of those tracks, on a fairly regular basis…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Excellent piece! Mother Meera is also the subject of Andrew Harvey’s “Hidden Journey”, which I can recommend. Here’s an old review over at Tricycle.

https://tricycle.org/magazine/hidden-journey-spiritual-awakening-2/

LikeLiked by 2 people